The Key to Richmond

A New York private and two of his comrades carefully crept their way into Petersburg, Virginia on the morning of April 3, 1865. Separated from their regiment after the chaotic previous day, the trio could not resist the temptation to explore the city that had remained elusively out of reach the previous 292 days of the campaign. The most adventurous of the three poked into a landmark at the center of the city to nab a souvenir that best represented the rapid unraveling of the Confederacy in central Virginia.

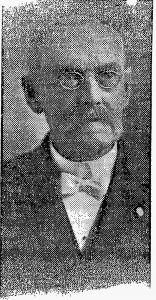

George Bell Herrick was born in West Bloomfield, New York on May 28, 1834. Having already gotten off to a promising mercantile career by the age of seventeen, he decided to forego that business to become a compositor at a local newspaper. Throughout his life he served as editor and correspondent at ten different papers across New York. Herrick also assisted with the local fire departments at these various stops in his career.[1]

On September 11, 1862, Herrick mustered in as a private in the 33rd New York Infantry. Having enlisted for three years of service, Herrick transferred to the 49th New York Infantry when his original unit’s term expired in May 1863. Both regiments fought in the Army of the Potomac’s Sixth Corps. While at the front Herrick served as a correspondent for the Rochester Union & Advertiser. The newspaper did not attach bylines to the soldier letters it ran so I have not been able to determine which of the published correspondence Herrick might have sent. Either way, the paper did not publish anything from the 49th Regiment during my period of focus, the spring of 1865.

Herrick was on the skirmish line overnight before the decisive Petersburg Breakthrough on the morning of April 2, 1865. Throughout the long night they kept up an intermittent fire, carefully attempting to balance the usual amount of sporadic activity between the lines without provoking too great a response that would reveal the attack columns forming behind them. The 14,000-strong Sixth Corps silently suffered significant casualties, including the mortal wounding of Lt. Col. Erastus D. Holt, commanding the 49th New York, before the signal gun jolted the massive wedge forward at 4:40 a.m.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles A. Milliken, 43rd New York Infantry, temporarily commanded the division pickets to which Herrick belonged that day. Milliken reported that the skirmish line took part in the successful attack and helped capture the picket posts opposite them near the burnt home of Robert H. Jones along Church Road. They continued onward into the main line of Confederate entrenchments along the Boydton Plank Road and captured three pieces of artillery. Milliken’s skirmishers advanced as far as Fort Gregg before Confederate Maj. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox, commanding a division in A.P. Hill’s corps, scraped together a refugee force to counterattack and prevent the Federals from reaching the Dimmock Line—Petersburg’s inner line of defense.[2]

The rest of the Sixth Corps swung south to clear the line to Hatcher’s Run and the Twenty-fourth Corps moved into position to assault Fort Gregg. Milliken meanwhile rested and refitted his command and settled into place screening the main Union line from the Confederates tucked into the final defenses around Petersburg. That night Robert E. Lee pulled the Army of Northern Virginia out of the city.

On the morning of April 3, Herrick and two others who had been out on the picket line with him ventured into Petersburg. Their likeliest avenues into the city lay along Washington Street and Halifax Road. Near the junction of the two sat the home of Thomas Wallace, which hosted a meeting that morning between Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. Herrick witnessed their greeting and exchanged congratulations of his own with Col. Ely Parker of Grant’s staff. This was the third time Herrick claimed to have seen Lincoln. He was present in Rochester when the President-elect briefly stopped on his train ride to Washington in 1861 and claimed to be nearby at Fort Stevens in 1864 when Lincoln observed the Sixth Corps under fire just outside of Washington.

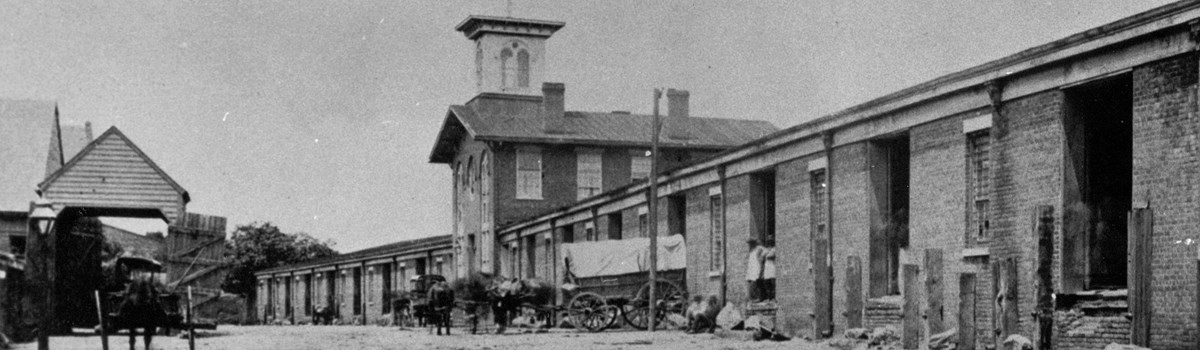

After observing the famous gathering at the Wallace house, the New York trio continued into the city until reaching the South Side Railroad depot. Until broken by the Sixth Corps the day before, the railroad had served as the last major supply line into Petersburg. It was also the route that Lee intended to take should he need to withdraw. A roundabout detour involving multiple crossings of the Appomattox River fatally delayed the Army of Northern Virginia over the next week. Meanwhile at the depot, Herrick helped himself the key to the station’s door. “Granting that the Southside road was the key to Richmond,” noted a local New York paper decades later, “it is generally conceded that the key now in the comrade’s possession is the veritable key to Richmond.”[3]

Though it took no unusual bravery or notable incident to secure it, the symbolism of Herrick’s trophy is justified. Grant placed his armies into a position around Petersburg and Richmond that offered multiple ways of winning the war—the destruction or capture of Lee’s army, a successful assault that would outright capture either city, the strangling of Confederate resources until Lee’s position became untenable, or simply holding Lee in place while other Federal armies mopped up their lesser opponents elsewhere.

Ultimately, the loss of his railroad connections forced the Confederate commander to abandon Petersburg (and thus Richmond as well). Until then, nothing had been able to convince Lee otherwise—be it the hopeless reports from other scattered armies, the inability to regain the strategic initiative, the futility of the Confederate assault on Fort Stedman, the unprecedented powerlessness to stop Grant’s final offensive during its first four days, or the one-sided result of the fighting out at Five Forks. Lee only conceded Petersburg’s fate as Union soldiers streamed toward the South Side Railroad west of his headquarters after they broke through on April 2nd.

No special recognition is probably due Herrick for poking around an empty building, at least none more so than would be given to any other Union soldier who participated in the attacks around the city. However, some unidentifiable thing that he did during the final campaign must have impressed his commanders. The private received a symbolic gesture right as he mustered out of the service—a leapfrog promotion to first lieutenant and adjutant.

George Herrick returned to the newspaper trade in New York and married Mary E. Wildman on September 28, 1869. The couple lived in Brooklyn, Batavia, and Rochester before returning to Mary’s hometown of Whitesville. George also prominently served in the Grand Army of the Republic postwar organization and continued to offer support to his local firehouse as well as the Methodist church to which he belonged. He died on September 24, 1920, peacefully passing away as he sat by the window in his easy chair and thus closing “the life record of a gentleman, scholar and patriot tried and true.”[4] Throughout that life Herrick held onto his prized Petersburg possession.

Sources:

[1] “Comrade Herrick 81 Years Old,” Allegany County News, May 27, 1915.

[2] Charles A. Milliken to Charles Mundee, April 17, 1865, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, vol. 46, pt. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894), 962.

[3] “Col. Herrick in Rochester,” Whitesville News, August 31, 1911.

[4] “George Bell Herrick,” Whitesville News, September 30, 1920.

Fascinating account… Thanks for bringing George Bell Herrick and his exploits to our attention. [And just one bit to add: likely it was Herrick’s “nose for a news story” that helped position him — right place, at the right time — in proximity to Abraham Lincoln. Good Reporters can extract leads from bits of data that most people assume are unimportant.]

A little petty larceny is preferable to rape, pillage and sack. Reminds me of the Berchtesgaden souvenir hunt by the 101st when they were the Fuhrer’s uninvited guests.

So, where is the key now?