Cryptic Entries: The Puzzling Diary of Captain Edmund O’Brien

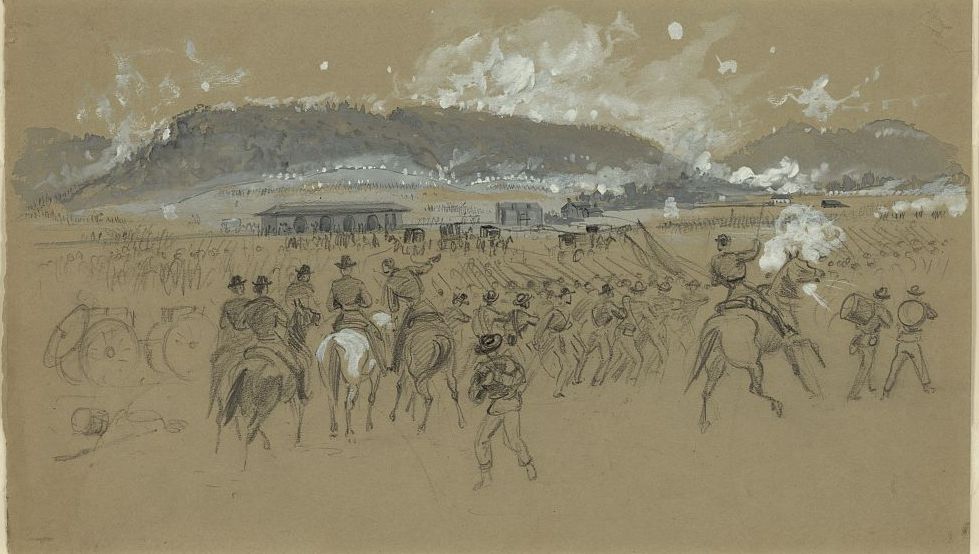

Braxton Bragg’s army was in desperate straits. Defeated and demoralized from their stunning defeat atop Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, the Confederates trudged southward, anxious get their artillery, supply wagons, and troops through a gap in the mountains at Ringgold, Georgia. From there they could fall back to Dalton, regroup, and prepare for the next Federal onslaught. General Ulysses S. Grant ordered Major General Joseph Hooker and 16,000 men from four corps to cut off Rebel supply lines at the Western and Atlantic Railroad. Bragg ordered Major General Patrick Cleburne and his single division of 4200 men to defend the gap long enough to allow the Army of Tennessee safe passage. It took Hooker’s force all day on November 27 to reach Ringgold where the Federals camped within three miles of the enemy.

The next morning, Hooker ordered Brigadier General Charles Woods of Peter Osterhaus’s 1st Division, 15th Army Corps, Army of the Tennessee to enter the gap and probe for the enemy, despite the fact that artillery had not yet arrived. Cleburne had taken a strong tactical position, manning the heights on either side of the defile. Halfway up the slope of White Oak Mountain to the north, Cleburne hid behind a tree while seven Texas regiments under the command of Colonel Hiram Granbury laid prone amidst a large stand of timber, awaiting the signal for ambush. Just after 8 a.m., part of Woods’s vanguard brigade began to scale the rocky slope and were met with heavy fire from as close as fifty yards.

Captain Edmund K. O’Brien’s Company “A” and the rest of Colonel James Peckham’s 29th Missouri Volunteer Infantry marched face first into the firestorm, following fellow Missourians from the 17th and 31st, who were taking a terrible thrashing. Peckham’s regiment made a desperate attempt to outflank the Texan right, but Major W.A. Taylor, commanding four dismounted cavalry regiments, bent back his line and placed skirmishers at a right angle in the trees above them. As the Federals climbed the 45-degree slope, Taylor and three companies dashed down on them, seized their colors, and sent the three regiments scrambling back down the mountain to safety behind a railroad embankment. Rebels captured dozens of prisoners, including Captain O’Brien, and shuttled them behind Confederate lines. Cleburne held on for five hours, allowing Bragg’s train and soldiers to escape.[1]

O’Brien’s fighting days were over. He spent the remainder of the war in six different prison camps, escaping unsuccessfully on two occasions. He chronicled his service in three diaries that began with his participation at the fall of Vicksburg, Mississippi in July, 1863 and continued through the Confederate surrender. His great granddaughter contacted me for assistance in transcribing portions of the diary that appeared indecipherable. Most of O’Brien’s account was clearly written in legible cursive consistent with his high school education, yet there were about a dozen entries that looked very different. These pages are scrawled in a messy, hurried manner inconsistent with O’Brien’s typical script. What could account for these discrepancies?[2]

The timing of O’Brien’s scribbled entries offered a clue. They roughly coincided with his

capture. The mysterious passages begin on November 24 and 25, two days when he would hardly have had the time to write, as his regiment was engaged in battle at Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. Was he seriously injured at Ringgold Gap, thus hampering his handwriting? Not likely, as he makes no mention of being wounded or recovering. Were these entries written in code to protect sensitive information from his captors? That motive makes sense, but the theory that parts of these passages were coded was dismissed by a cryptology expert. Did O’Brien employ shorthand to conceal details of his entries while unable to disguise place and proper names that have no shorthand equivalents? The illegible characters do not appear to be shorthand. It finally dawned on me that although O’Brien was an Irish American, he lived in eastern Missouri in an area full of German Americans. I asked two experts to weigh in and both agreed that the confusing entries in O’Brien’s diary were written in German Kurrentschrift, a medieval form of cursive writing that persisted into the late 19th century.

O’Brien lived in the heavily German city of Saint Louis where Irish and German Catholics often worshipped together during a period when Know Nothing anti-immigrant sentiment combined with a strong bias against Catholics like him. Whether he was attending parochial school or working as a clerk in his father’s fur trading business, some familiarity with German words would have been essential for a young man engaged in commerce. The 1850 U.S. census records a 35-year-old women and namesake of Edmund’s younger sister Marian living with the family and born in Bavaria. Edmund’s widowed aunt, perhaps? In any case, Edmund must have felt confident that few Confederates could read the archaic cursive, much less understand German.[3]

O’Brien writes in German for a little more than a month, then abruptly returns to English in January 1864, while in Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. Had he spent enough time there to safely stash the diary away from the prying eyes of Confederate guards, or did he determine that what little news he did receive while imprisoned was already common knowledge, thus negating the need for secrecy? We may never know. In any case, O’Brien records that he “commenced the study of German” in July, 1864. Perhaps fluency in another language might again prove useful.

POW diarists left Civil War historians an intimate record of life in prison camps. Contemporary letters and diaries are considered valuable primary sources, but must be compared and contrasted to get closer to what really happened inside the prison walls. Earlier this year, another descendant of a Union officer and prisoner-of-war sent me images and transcripts of another unpublished diary, the account of Lt. Abram Songer. You may read about it here:

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/03/23/a-hidden-gem-of-a-civil-war-diary/.

Coincidentally, both diarists were confined in the same Confederate prisons during nearly identical time periods, thus offering many opportunities to compare their accounts.[4]

O’Brien and Songer were Libby Prison inmates during the famous escape of February 9, 1864. Songer’s account agreed precisely with contemporary news media and later recollections of the two ringleaders in relating that 109 Union officers escaped. O’Brien claimed that 130 made their way through the tunnel. Andrew J. Hamilton, one of the masterminds of the prison break, estimated that 48 officers had been recaptured within three days.[5] O’Brien lists the number of fugitives returned day by day, concluding that 39 had been tracked down by the fourth day, and about 50 recaptured in total. Admitting some room for rumor and error, the various accounts jive closely and lend credence to later recollections of escape organizers and escapees themselves. In other cases, however, memory was reshaped for partisan purposes.

Lt. Duncan Forsyth, an ill twenty-three-year-old adjutant of the 100th Ohio, was gasping for fresh air near one of Libby Prison’s upper middle room north windows when a bullet from one of the guards in the yard below ripped through his left eye and exited his skull, killing him instantly and wounding Lt. D.O. Kelly in the neck with skull fragments. Songer related that the guards were loading their guns “when one of them (said to be) accidentally discharged his gun.” O’Brien claimed that “as the guards were loading and priming their guns accidentally went off.” Contemporary newspaper accounts and a letter from Lt. Colonel E.L. Hayes on the 100th Ohio confirmed that the shooting was an accident.[6] By 1893, some northern papers suggested that the killing was intentional, as the “guard was under orders to shoot anyone looking out of a window.”[7]

While O’Brien and Songer were in custody at Camp Oglethorpe near Macon, Georgia, they wrote of numerous violent incidents that were not accidental. Shortly after dusk on June 12, 1864, Lt. Otto Grierson of the 45th New York Infantry was returning from a trip to the spring where one could get a drink of water when he was, according to O’Brien, “deliberately shot.” He died at 2:30 the following morning. Songer was about thirty feet from the mortally wounded man when it happened and commented that Grierson was ten or twelve feet from the dead line and was not warned to halt. “The man who shot him was Richard Barrrett, Co C Augusta Battalion,” Songer revealed. “I presume he just wanted to kill a Yankee. Under the circumstances it was willful murder.”

On November 4, Songer reported that more than 300 men escaped as prisoners paroled to gather pine boughs and other shelter got mixed up with prisoners inside the dead line and confused the guards. O’Brien added that forty men in his area counted twice in the morning and evening to deceive the guards and more than 200, including O’Brien himself, made their escape. They first traveled in parties of six, then broke into pairs to further disperse. O’Brien paired up with Lt. Oscar Rhone of the 184th Pennsylvania Infantry and they sought out slaves who would help them find food. The old black man who fed them and gave them directions said that fifteen other fugitives had been seen in the vicinity that same day. A tantalizing four diary pages are missing but it is clear that O’Brien was recaptured after just a few days on the run. The vast majority were brought back by Confederate soldiers using bloodhounds in the same manner by which enslaved people were hunted down in their attempts to reach freedom. Both men wrote that two hounds wandered into camp. They were quickly dispatched with an ax and buried in a shallow grave. Upon discovering the canine corpses, some guards threatened to tie them in the spring to foul the prisoners’ drinking water, while others threatened to shoot four Yankees in retaliation.

So many Civil War diaries like these are in private hands, seldom available to scholars for research. Comparing accounts from multiple soldiers who witnessed the same event is crucial to getting closer to the historical truth, if such a thing actually exists in a world where every human is subject to bias and personal motive. Nevertheless, the similarities in these two unpublished accounts is striking and gives this historian hope that many more people will share and collaborate so we can all learn and enjoy these precious relics of one of our nation’s great tragedies.

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (2020 Univ. of Tennessee Press).

[1] Peter Cozzens, The Shipwreck of Their Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga (Chicago: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1996), 366 ? 84.

[2] Diary of Edmund K. O’Brien, Private Collection.

[3] 1850 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com, 1997.

[4] Diary of Abram W. Songer, Private Collection.

[5] Andrew G. Hamilton, Story of the Famous Tunnel Escape from Libby Prison (Chicago: S.S. Boggs, 1893).

[6] Richmond Enquirer, 14 April, 1864. Perrysburg (OH) Statesman, 4 May, 1864.

[7] National Tribune, 29 June, 1893.

Really interesting post David.

Great detective work: medieval cursive in German! I often wonder how difficult it is to get a good understanding of primary sources handwritten in English and weathered over 150 years. And bloodhounds and murder. How brave the prisoners were to continue the war. Great article. Thank you.

Kapitan O’Brien versteht Deutsch.

Before reading the entire article I scanned the enhanced (enlarged) diary extract and had a look: “funf Uhr” (five o’clock) and numerous umlauts gave it away. Then came back and finished the excellent article… which raised issues and inspired more observations than expected.

1) The use of foreign language as “low grade code” in writing of communications during the Civil War was common: Hungarian was the Federal language of choice, used by Fremont’s Department of the West, based at St. Louis.

2) Camp Oglethorpe, a fairground at Macon Georgia initially used as Rebel recruitment station, was converted to POW prison pen in time to incarcerate 2000 Shiloh prisoners in Spring 1862. Although baseball was initially allowed to be played by prisoners on the sprawling field, totally enclosed by a high board fence, a new Commandant in June 1862 (Major Rylander) instituted the “dead line” …and cut food rations to bare minimum (unofficially “half-rations”) …and ended the playing of sport.

3) Confederates, especially at Macon Georgia, and Montgomery Alabama seem to have directed added animosity towards Battle of Belmont POWs and captured Missourians- in- Federal service. The Shiloh POWs belonging to Federal Missouri regiments were the LAST to be released from Camp Oglethorpe (in OCT/ Nov 1862) so perhaps by time 29th Missouri Captain O’Brien was taken prisoner he was aware that “he had to conduct himself with an extra degree of caution.” [Primary resource: “A Perfect Picture of Hell” (2001) ed. By Genoways & Genoways.]

A little bit of Dan Brown