Rolling on the River: Civil War Brown-Water Navies

A blue-coated rider appeared atop the riverbank above the bow of the steamer Belle Memphis. Rebels massed in the cornfield behind him discharged volleys that whistled by the horseman, whanged through the tall smokestacks, and thudded into the vessel’s superstructure. Hundreds of Iowa and Illinois infantry had already slithered down the muddy incline and scrambled aboard to escape numerically superior forces threatening to envelop them. The steamer captain pulled in his mooring lines but delayed starting engines; men on deck dropped a board across the water gap.

The rider—a superb equestrian—recalled: “My horse put his fore feet over the bank without hesitation or urging, and with his hind feet well under him, slid down the bank and trotted aboard the boat, twelve or fifteen feet away, over a single gang plank.” Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant, the last man over, nimbly dismounted and ascended to the upper deck.[1]

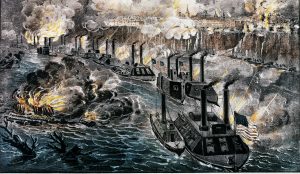

Belle Memphis and the other half dozen troop transports opened their steam valves. Engines rumbled; smoke billowed, and paddlewheels thrashed as they backed off the shore and began pulling upstream carrying Grant and his 3,000 men out of danger. Farther out and a bit downstream, Commander Henry Walke, U. S. Navy, observed from the river gunboat Tyler as she and the gunboat Lexington lobbed broadsides into Confederate lines ashore.

“The enemy’s artillery was seen tumbling over, and his ranks were soon broken,” wrote Walke. “They dispersed in the utmost confusion, or fell on the ground to escape our shot and shell.”[2] Concluded General Grant: “We were very soon out of range and went peacefully on our way to Cairo [Illinois] every man feeling that Belmont was a great victory and that he had contributed his share to it.”[3]

Opinions differed as to how great was the victory, but the Battle of Belmont, Missouri, November 7, 1861, on the banks of the Mississippi River was the first major command engagement for the future general in chief. It also was the first significant joint army-navy operation on the rivers. Overseeing his gunboats and troop transports, Commander Walke rapidly delivered Federal forces to where they were not expected, covered their landing, suppressed enemy batteries on the bluffs of Columbus, Kentucky, across the river, obstructed Rebel reinforcements crossing the stream, scattered attacking gray ranks at the river, and neatly extracted Union fighters when the odds turned.

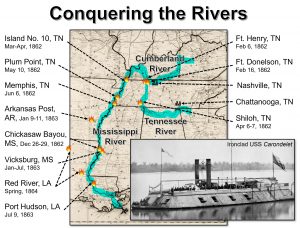

The campaign for the Lower Mississippi and its tributaries—the spine of America—was one of the longest and most challenging of the Civil War encompassing over 1,000 twisting river miles (double what the crow could fly) from Cairo, Illinois, to New Orleans cutting through six states in a massive alluvial flood plain averaging 75 miles wide, the best cotton land in the world. The river’s name derives from the Ojibwa (Chippewa) word Misi-ziibi or the Algonquin term Missi Sepe, usually rendered as “great river” or, more poetically, “father of waters.”

“But what words shall describe the Mississippi,” asked English novelist Charles Dickens after his 1842 tour of America. “An enormous ditch, sometimes two or three miles wide, running liquid mud, six miles an hour: its strong and frothy current choked and obstructed everywhere by huge logs and whole forest trees. . . . The banks low, the trees dwarfish, the marshes swarming with frogs, the wretched cabins few and far apart, their inmates hollow-cheeked and pale, the weather very hot, mosquitoes penetrating into every crack and crevice of the boat, mud and slime on everything: nothing pleasant in its aspect, but the harmless lightning which flickers every night upon the dark horizon.” [4]

The river’s western banks (also called the right banks looking downstream) are generally low while on the east (left bank) side frequent heights, hills, or bluffs provided most habitable sites. Major southward-flowing tributaries—the Ohio, White, Arkansas, Yazoo, and Red—branched 500 to a 1,000 or more river miles up and out from the trunk. The northward-flowing Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers penetrated downward from the Ohio River in middle Tennessee deep into some of the South’s principal grain-growing, pork-raising, mule- and horse-breeding, and iron-producing regions.

Dominance of the rivers was a paramount strategic objective for both sides, so crucial that the federal government would name its principal field armies after them. Early in the war, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman wrote to his wife Ellen: “I think the Mississippi the great artery of America, whatever power holds it, holds the continent.”[5]

Dominance of the rivers was a paramount strategic objective for both sides, so crucial that the federal government would name its principal field armies after them. Early in the war, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman wrote to his wife Ellen: “I think the Mississippi the great artery of America, whatever power holds it, holds the continent.”[5]

Referring to the seasonal “June rise,” the New York Times in May 1861 opined: “Inasmuch as the Mississippi River is one of the most dangerous agencies that may be employed against the welfare and wealth of the South, it is well to make note of the coming flood,” a reference that would become as much martial as natural. On eastern maps, rivers like the Rappahannock-Rapidan line were east–west defensive barriers to the Confederacy’s advantage; in the west, rivers were north–south avenues for Union assault.

The new commander in chief, himself a product of the west, understood the rivers. As a young man, Abraham Lincoln barged down the Ohio and Mississippi to New Orleans experiencing firsthand these vital arteries of transportation and commerce. Despite differing political interests across the region, the great rivers created a vigorous economic unity in a huge market up and down the middle third of the continent, linking rural southern communities with northern urban centers.

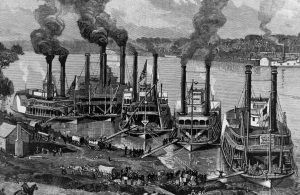

Railroads had been advancing west but low-powered locomotives on single tracks along limited networks could not compete with steamboats in carrying capacity or area coverage, and they were vulnerable. “I am never easy with a railroad” wrote Sherman, “which takes a whole army to guard, every foot of rail being essential to the whole; whereas they can’t stop the Tennessee [River] and each boat can make its own game.”[6] On another occasion: “The Mississippi boats were admirably calculated for handling troops, horses, guns, stores, etc., easy of embarkation and disembarkation, and supplies of all kinds were abundant. . . .”[7]

Unschooled as he was in military matters, the president intuitively grasped strategic concepts including the importance of surrounding and strangling rebellious states. Lincoln’s first major executive decision—one week after the fall of Fort Sumter—declared a blockade of Southern ports as the primary mission of the United States Navy. The concept logically extended up the rivers slicing through the vitals of the Confederacy as proposed by Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott in what became known as the Anaconda Plan.

Lincoln also advocated the strategic offensive: coordinated advances on multiple fronts—east and west, land and water—employing superior resources and transportation along exterior lines. Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton would create a robust riverine force from nothing and, under the president’s watchful eye, usually coordinate on strategy. On the other hand, given its limitations, the Confederacy would rely primarily on defensive fortifications, force concentration along interior lines, and decisive battle.

Beneath the strategy, however, both navies confronted novel challenges not usually found at sea. Rivers and oceans are distinct maritime environments; the vehicles and skills required to exploit them differed accordingly. The millennia-old technology of sail still ruled open water. Although rapidly developing, steam engines were not sufficiently reliable or efficient to be the primary, much less the only, mode of propulsion across trackless oceans, and so they remained auxiliary to wind.

Conversely, rivercraft relied solely on steam power where fickle breezes would not work. They operated along swift flowing, shifting, meandering, constricted, shallow, sand banked, wreck and snag infested rivers and swamps, environments the ocean sailor viewed with trepidation. In addition to the diverse topography, seasonal variables—rains, snows, floods, drought—caused dramatic fluctuations in water depth, breadth, and current along each distinct stretch of every river. Rivermen required extensive experience with local conditions to operate their—temperamental and delicate—broad-beamed, shallow-draft, high castled vessels.

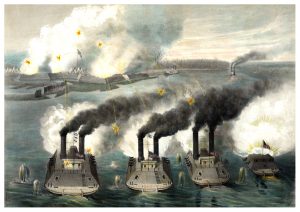

Both navies began with no shallow-water warships, no tactics, no command structure, no infrastructure. Nascent technologies of steam propulsion, iron armor, and heavy naval artillery were untested in river combat. Neither navies nor armies were versed in the relatively new—less than a half century old—business of steam rivermen and rivercraft now swarming heartland waters.

Union wooden and ironclad gunboats of the Mississippi River Squadron would confront Rebel counterparts, fortifications with heavy shore batteries, torpedoes (mines), guerrillas, and a hostile populace. They reconnoitered and patrolled, transported and sustained land forces, conducted amphibious expeditions and sieges, provided heavy artillery support, interdicted enemy trade and transportation, and defended friendly commerce.

Federal riverine units also supported civil-military stabilization, occupation, and reconstruction, i.e., “showed the flag.” They aided and enlisted escaped slaves and freedmen. Confederates, meanwhile, struggled valiantly but ineffectually to respond with their own gunboats and ironclads.

Despite a lack of a joint operating perspective, outstanding Union commanders emerged. Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, Flag Officer Charles H. Davis, and Admiral David D. Porter developed effective partnerships with army counterparts, particularly with Generals Grant and Sherman. Both generals, also sons of the west, readily incorporated maritime elements as integral combat and logistic arms and credited them in victory. Sherman wrote about a navy colleague: “Of course we will get along together elegantly. All I have he can command, and I know the same feeling pervades every sailor’s and soldier’s heart. We are as one.”[8]

Riverine warfare was an indispensable component of the western campaigns as well as a unique chapter in the country’s naval history. A case can be made that the war was won in the west. If so, it was won on and near rivers by some of the era’s most capable naval professionals leading citizen sailors in unique war vessels, often at the tip of the spear alongside renowned generals and their soldiers.

This is the story of an unprecedented army-navy symbiosis that proceeded through many trials bigger than Belmont—Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, Island No. 10, Memphis, Vicksburg, Port Hudson, Red River—until Abraham Lincoln could declare: “The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”[9]

————

[1] John F. Marszalek, ed., The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), 195.

[2] H. Walke, Naval Scenes and Reminiscences of the Civil War in the United States, on the Southern and Western Waters During the Years 1861, 1862 and 1863 with the History of that Period (New York: F. R. Reed & Company, 1877), 38.

[3] Marszalek, ed., Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, 195.

[4] Charles Dickens, American Notes for General Circulation Annotated (London, 1842), 185.

[5] William T. Sherman to Ellen Sherman, June 10, 1862, University of North Dakota, Sherman Family Papers.

[6] Sherman to Porter, October 25, 1863, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 2 series, 29 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922), series 1, vol. 25, 474.

[7] William T. Sherman, Memoirs of Gen. William T. Sherman, Volume 1 (Kindle edition), 203.

[8] Sherman to Porter, October 25, 1863, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 2 series, 29 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922), series 1, vol. 25, 474.

[9] Abraham Lincoln to James C. Conkling, August 26, 1863, in Merwin Roe, ed., Speeches and Letters of Abraham Lincoln, 1832-1865 (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co, 1907), 223.

thanks Dwight, great essay … i am again reminded about how easily joint army-navy operations seemed to come to the Union officers … not a lot of backbiting, no big arguments over tactics or who was in charge … great teamwork. thanks again.

Thanks Mark. Cooperation came easy to some officers–Grant, Sherman, Porter–but not so much to others. Halleck refused to support Farragut at Vicksburg in the summer of ’62. If he had, the city could have been taken then.

I am looking forward to this series. I got goosebumps when Grant’s horse made it to the Belle Memphis. What is the naval version for “Huzzah?”

Winfield Scott… they might should have kept him in charge for a bit longer.

Sam Grant was an easygoing man who got along with other men. His shy, diffident personality helped him get along with senior naval officers like Foote, Farragut and David Dixon Porter. Grant’s long hardscrabble years spent puffing meditatively on seegars while he read newspapers and chewed the fat about national affairs with fellow civilians in country stores–in between tanning hides, taming horses and selling firewood–had given him a perspective that vainglorious officers like Fremont and McClellan lacked. When the Civil War began, the Union Army was top-heavy with showboating brass who had their own ideas about how it should be conducted and the terms on which it should be concluded. Grant was also lucky in that his star started to shine at about the time when Lincoln grew into his job and found it easier to dismiss insubordinate and incompetent officers. Grant’s early engagements at Belmont and his victories at forts Henry and Donelson gave him a certitude that never deserted him and served him well after the initial shambles at Shiloh and the bloodbath at Cold Harbor.

Reading this in a Vicksburg hotel after a 2-day Cleveland Civil War Roundtable tour of Vicksburg. Good introduction by Mr. Hughes.