Mexican War Hero Alexander W. Doniphan: One of the Civil War’s Great “What Ifs”

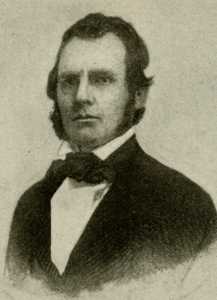

Some of the most thought-provoking “what ifs” of the Civil War involve noteworthy individuals that chose not to or could not participate in the war. Instead of taking up arms for one reason or another, they remained on the sidelines during the conflict. Colonel Alexander W. Doniphan is one such individual.

During the Mexican War, Doniphan led 800 volunteers 3,500 miles across precarious terrain into Mexico, helped to capture New Mexico, and defeated a Mexican force roughly four times the size of his own at the Battle of Sacramento in February 1847. His success during the war made him a national celebrity. Doniphan was arguably one of the most famous Missourians in 1861.

For Alexander W. Doniphan, picking a side during the rebellion was no simple decision. He was a strange mix of a slaveholding southerner who was outraged by Lincoln’s use of force against the southern states, while also adamantly opposed to secession and in favor of preserving the Union. Early during the war, newspapers tried to guess which side the war hero would join. He chose to remain neutral. There undoubtedly would had been great political and military ramifications if he donned a blue of gray uniform and took up arms. Doniphan is one of the great “what ifs” of the Civil War most people have never heard about.

“Ignorant Country Buffoon”

In early February 1861, on his way to Washington, D.C., to participate as a commissioner in the Peace Convention, Alexander W. Doniphan bumped into his old Augusta College classmate Orville Hickman Browning. Even though they had not seen each other since they left college 30 years before, Doniphan immediately recognized Browning. Their friendly encounter quickly turned into a heated discussion about secession. “He is professedly a strong Union man,” Browning wrote about Doniphan in his journal after the chance meeting in an Illinois train station, “but thinks the government has no power to protect itself against the attempts of a state to break it up, and that any effort to do so will drive all the slave states into combination with the traitors of South Carolina.” Doniphan opposed President Abraham Lincoln using military force against the southern states, even though he despised secession talk. Instead, he advocated compromise and hoped the Peace Commission would help to keep the Union together. The commission ended up being a wasted effort as Browning had anticipated.[1]

While in Washington, D.C., Doniphan and several other commission delegates were introduced to Lincoln at Willards Hotel. “Is this Doniphan, who made that splendid march across the Plains, and swept the swift Comanches before him?” Lincoln reportedly said to the old war hero. Doniphan replied with a modest comment stating that he was the man who commanded the expedition. “Then you have come up to the standard of my expectation,” Lincoln declared. While both were former Whigs, Doniphan viewed Lincoln as an unintelligent, oppressive tyrant. He had voted for the Constitutional Union Party and its candidate John Bell in the 1860 election. “[I]t is very humiliating for an American to know that the present & future destiny of his country is wholly in the hands of one man, & that such a man as Lincoln,” Doniphan wrote to his nephew, John, on February 22, 1861. “Old Able is simply an ignorant country buffoon who makes about as good stump speech as Jim Craig, and will not be more fitted intellectually as President, but perhaps as disinterred.” It must have pained Doniphan to be in the same room with Lincoln at Willards and forced to engage in small talk with him.[2]

Disgusted with the outcome of the Peace Commission and the man in charge of the nation, Doniphan appeared the closest he was during the war to endorsing the rebellion. He anticipated that the Union would be dissolved in a few days or months at most. “Missouri must demand what the other slaves states demand and remain—as a unit—and by one act—and form a new GOV’T or go with the South—and this last is best,” he wrote to his nephew. It sounded as if Doniphan was prepared to support a cause bent on destroying the nation he fought for 14 years before. His subsequent actions proved otherwise.[3]

Taking Up Arms

Reports circulated that Doniphan intended to cast his lot with the Confederacy and fight against the U.S. government. His chance came on May 14, 1861, when Governor Claiborne F. Jackson appointed him brigadier general of the Fifth Military District. The appointment proved to be Doniphan’s watershed moment during the war. He could either support the Confederacy by drawing his sword against the U.S. government or refuse to participate in the rebellion.

Doniphan mulled over Jackson’s letter, and sent a well-thought-out reply on May 23. He declined the brigadier general’s commission, providing several reasons for doing so. These included his age, his wife’s poor health, his hope that peace could still prevail, and more. Jackson instead appointed his second choice, Mexican War veteran Alexander E. Steen, to fill the position. Steen would go on to fight at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, and was killed during at the Battle of Prairie Grove in December 1862. Mexican War veteran Sterling Price became the leading man in Missouri as major general of the Missouri State Guard, a position that Doniphan would have been well suited for.[4]

Pro-Confederate newspapers said Doniphan joined the rebellion, while pro-Union newspapers adamantly denied it. For instance, on September 19, 1861, the Hannibal Daily Messenger claimed the St. Joseph Gazette was spreading rumors. “Some ten days or two weeks since the St. Joseph Gazette, a notorious rebel sheet started the story that the distinguished hero and Union patriot Col. A.W. Doniphan of Liberty, Clay County, had deserted and gone over to the enemy, and would soon take the field in person,” the newspaper declared. “Knowing Col. Doniphan as we do, we considered the story so obscure and ridiculous that to be worthy of credence, and therefore paid no attention to it; but now the Quincy Herald takes it up and reiterates it in its issue of Tuesday, and makes it still more incredulous by stating that Col. D. ‘has called for 30,000 Missourians to join him’ in his crusade.” The paper then went on to assure its readers that he was quietly attending to his private business and had no role in the present troubles. False reports that Doniphan was fighting as a Confederate general continued into the fall of 1861.[5]

Union or Death

If anyone doubted Doniphan’s allegiance to the U.S. government, even with his aversion for Lincoln, he settled it once and for all with his pro-Union rhetoric. During a speech at Liberty in April 1862, he reiterated “that secession was hopeless” and that “that it would require 250,000 men to take Missouri out of the Union.” He scolded those who had not taken his advice and chose to enlist in rebel service, which brought destruction and ruin upon them. Now these same men came to him and asked what they should do about the military authorities taking their property and the government not protecting them. He told them they have no right to expect or ask for protection from a government that they tried to destroy. “Many a noble-hearted man who fought with me under the glorious stars and stripes in Mexico,” Doniphan declared, “was led off by this delusion of secession to fight against it, and now is ruined.” He advised all those who acted against the government “to come forward like honest and manly men” and comply with the demands of the government, which would permit them to find safety and happiness.[6]

Doniphan even went so far as to aid U.S. military forces during the winter of 1862. He rode 25 miles to Plattsburg to report that a former Mexican War comrade who authored a book about his expedition, Colonel John T. Hughes, was headed to destroy the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad and recruit soldiers for Price’s army. “Now, you know that all that would not disturb me nor hurt the State, for he would take out with him an element which would be better out than in,” Doniphan admitted to Colonel James H. Birch, a boyhood friend. “But what I am looking to is this. After he leaves and the Federals come in, there will be h—ll to pay.” The only way he felt he could avoid a bloody confrontation between pro-Union and pro-Confederate civilians was to prevent Hughes from crossing the Missouri River. Birch reported the intelligence he received from Doniphan to Major General Henry W. Halleck, who sent a force to Albany to block Hughes from crossing the river. The Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad was saved from destruction, U.S. control in the region maintained, and bloodshed avoided.[7]

Sterling Price 2.0?

With his finances in ruins and wishing to escape the guerilla war raging in Missouri, Doniphan relocated with his wife to St. Louis. He took a position as a special claims agent handling cases of widows and children of Missouri soldiers in February 1864. The former Whig-turned-Constitutional Unionist reluctantly voted for Democrat George B. McClellan during the 1864 election.“[I]t is McClellan or death in the opinion of the border state Democrats,” he declared. Anything but Lincoln would do. Doniphan relocated to Richmond, Missouri, in 1868, and there lived out the last two decades of his life.[8]

Alexander W. Doniphan fighting for the Confederacy or the Union would have had major consequences during the war. Taking up arms against the U.S. early in the war may have helped to turn the tide in Missouri for the Confederacy. Doniphan was possibly Governor Jackson’s first choice to command the Missouri State Guard instead of Sterling Price. Was Doniphan a superior general than Price? Would he had performed better in the same circumstances? What if he commanded the Confederate troops at Pea Ridge instead of Price? What would have been the outcome had he defeated Major General Samuel R. Curtis’ army in March 1862?

Doniphan was a natural leader of men, and had an established a reputation for his military ability despite any formal training. His success during the Mexican War and experience leading volunteers would have made him a natural fit for an important position in the Confederate Army. Would he have eclipsed his performance during the Mexican War? Would he have become one of the great Confederate lieutenants of the war? Likewise, what would have been the repercussions had he become a Union general? Fellow Missourians reluctant to fight for the Union against the Confederacy might have followed suit and taken up arms alongside. These question will be forever be left unanswered. Regardless of if it was his intention or not, Doniphan did a great service to his country by sitting out of the war. He weakened the rebellion in Missouri and helped to prevent a Confederate takeover.[9]

Endnotes

[1] Orville H. Browning, The Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, Volume 1, 1850-1864, Theodore Calvin Pease, ed. (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1925); 451; Roger D. Launius, Alexander William Doniphan: Portrait of a Missouri Moderate (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997), 246-47; Alexander W. Doniphan to John Doniphan, February 22, 1861, C1935, The State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri; Joseph G. Dawson, Doniphan’s Epic March: The First Missouri Volunteers in the Mexican War (Topeka: University of Kansas Press, 1999), 213.

[2] “Mr. Lincoln’s first day in Washington,” The Constitution (Middletown, CT), March 13, 1861; “First Reception of the President Elect at Washington,” The Farmers’ Cabinet (Amherst, NH), March 1, 1861; Dawson, Doniphan’s Epic March, 211, 215-16; Launius, Alexander William Doniphan, 242-44, 247-48; Alexander W. Doniphan to John Doniphan, February 22, 1861.

[3] Gregory P. Maynard, “Alexander William Doniphan, the Forgotten Man from Missouri” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1973), 96; Launius, Alexander William Doniphan, 248; Alexander W. Doniphan to John Doniphan, February 22, 1861; The Oxford intelligencer (Oxford, MS), May 22, 1861.

[4] “Journal of the Senate of the State of Missouri, Begun and Held at the Town of Neosho, Newton County, MO.,” Tri-Weekly Missouri Democrat (St, Louis, MO), December 4, 1865; Launius, Alexander William Doniphan, 252-53; Dawson, Doniphan’s Epic March, 220-221; Louis S. Gerties, The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012), 28-9; “Military Appointments,” The Missouri Republican St. Louis, MO), May 28, 1861; William L. Webb, “The Story of Doniphan,” in Battles and Biographies of Missourians, or, The Civil War Period of Our State (Kansas City, MO: Hudson Kimberly Pub. Co., 1900), 278-80.

[5] “Col. Doniphan,” Hannibal Daily Messenger (Hannibal, MO), September 19, 1861; “The Rebel Army—The Chief Officer,” The Examiner (Frederick MD), November 13, 1861.

[6] Launius, Alexander William Doniphan, 251, 256; “Col. Doniphan’s Speech at Liberty,” Daily Missouri Republican (St. Louis, MO), April 14, 1862.

[7] James H. Birch, Pension Report, April 15, 1896, 54th Congress, 1st Session, House of Representatives, Report No. 1299, 4-5; Launius, Alexander William Doniphan, 255; Maynard, “Alexander William Doniphan,” 101; Webb, “The Story of Doniphan,” 281-82.

[8] Dawson, Doniphan’s Epic March, 224; Launius, Alexander William Doniphan, 261-64; Maynard, “Alexander William Doniphan,” 102-104; “A Manly Western Hero: Gen. Alexander W. Doniphan Dies in Missouri,” Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, UT), August 18, 1887.

[9] Launius, Alexander William Doniphan, 255; Dawson, Doniphan’s Epic March, 222, 224; “The Story of Doniphan,” 279-80.

Fascinating! Never thought to see what he was doing during the Civil War. This man is also very popular in Morman history for not wantonly executing Joseph Smith in Missouri.