Echoes of Reconstruction: E. P. Alexander in Washington and the Lincoln Assassination

ECW is pleased to welcome back Patrick Young, author of The Reconstruction Era blog

We all know that Ulysses S. Grant gave uncommonly generous terms of surrender to Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox in April, 1865. Rather than interning Lee’s men, he allowed them freedom to travel home.

To Grant’s surprise, hundreds of Confederates headed north after the surrender. Some were heading home. They were men from the Border States of Maryland and West Virginia who had joined the Confederacy. Others went north hoping to explore opportunities there while the Federal government paid their food and transportation costs. Still others hoped to leave the United States through ports like New York for the last outpost of slavery in Brazil.

This development alarmed the military commanders in the areas the Confederates were heading to. The war was still going on and they worried that Confederates infiltrating into the North could initiate a terror campaign in the Union heartland. When a Confederate cell carried out attacks on Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward on April 14, their worst fears seemed to be realized. The presence of scores of Confederates in Washington on the night of the Lincoln assassination led to rumors that more terrorism was afoot. Grant had given Confederates paroles to return to their homes, not to travel freely about the North. After the shooting at Ford’s Theater, military commanders began expelling Confederates from Maryland and Washington.

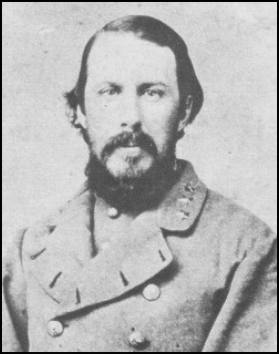

One northbound Confederate that unfortunate week was Brigadier General Edward Porter Alexander. The twenty-nine year old Georgian was one of the most respected artillery commanders in the Confederate armies. Unreconciled to defeat, E.P. Alexander suggested to Lee that he disperse his forces rather than surrender at Appomattox. After the game was given up, he decided to head to Brazil.

Alexander’s odyssey provides a look at the changing fortunes of those Confederates who left the Confederacy in the days after their war ended, but while other Confederate armies were still fighting. Alexander left an account of this time in his Fighting for the Confederacy: Personal Recollections of Edward Porter Alexander ed. by Gary Gallagher. His story begins with unexpectedly friendly treatment by some of the Union men he encountered. One was Senator Elihu Benjamin Washburne of Illinois. The senator, Alexander, and Confederate generals Wilcox and Gordon rode together with an escort of Union cavalrymen to protect them from marauding deserters. Alexander writes that the Republican senator “was exceedingly pleasant & courteous to us Confederates.” (p. 546)

When Alexander reached Farmville, Va., on April 12, 1865, he met with the son of the Republican governor of Pennsylvania. Alexander describes his reception, “The officer in command was a handsome & exceedingly nice, young General Curtin…. He took care of the whole party for the night, & took me actually to share his own pallet with him, & gave us all a good breakfast in the morning.” (p. 546) On the 13th of April, Alexander arrived in Burkeville, Va., where he surrendered his horse to the Union quartermaster. When the quartermaster tried to pay for the horse, Alexander declined the payment because it was not his personal property. He then boarded a train for City Point, Va. The Union army allowed Confederates travelling from Appomattox free rides on trains and steam ships so they could quickly get home.

The crowded train waited on the tracks for an hour, “while it waited some one came to the door of the car I was in & called “Alexander.” Not supposing it meant for me I made no reply. Then, “Is Gen. Alexander of the Confederate army here?” On this I spoke, & up rushed Gen. A. S. Webb, who had been an intimate friend at West Point in the old times. Regardless of the crowd he threw his arms about my neck, & hugged me saying, “I’ve got you at last. I’ve been trying to get you for four years & now I have got you.” Then we got in a corner behind the door, & he produced from one pocket a candle & a tumbler, & … a bottle of whiskey, & we renewed old friendship & discussed places where we had fought each other—particularly Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg— until the train left. His brigade had been at the very brunt of our assault.” (pp. 546-547).

On April 17, Alexander was in Richmond, and he called on his old commander. Alexander writes:

“Gen. Lee was staying in the city with his family, who had remained during the evacuation & the fire, & I called & spent an evening with them, all of his daughters being at home. Gen. Lee did not at all sympathise with my plan of going to Brazil. [Union] Gen. Ord was in the city, & in command of it. I called on him to get a permit to go to Washington City, & found him very cordial & pleasant.…” (p. 547)

Up until now, Alexander was gratified by the treatment he had received from his former enemies. Then ill omens appeared. According to Alexander:

Sunday evening I first heard on the streets rumors of the assassination of Prest. Lincoln. I did not believe it & went to Gen. Ord’s after supper to ask if it could be true. Gen. Ord confirmed it & advised me not to go to Washington City. But I did not know exactly what else I could do & decided to risk it. I left on Mon. morning in a boat which went down the James & up the Potomac, & landed me in Washn. on Tuesday the 18th. I had no sooner landed than I felt it in the atmosphere that I was in the wrong place. The streets swarmed like beehives. The president’s body was lying in the White House to be viewed, & the column, four deep, forming & marching past reached a half mile up Pa. Avenue.

Little was yet known of the plot which resulted in the murder, & it was naturally ascribed to Confederates in general. And somehow Mr. Davis, Mr. Clay, & others were supposed to be connected with it & rewards of $100,000 each were offered for their capture. The passion & excitement of the crowds were so great that anyone on the street, recognised merely as a Confederate, would have been instantly mobbed & lynched. In Richmond I had gotten a citizen coat & pants, & I wore a U.S. army private’s overcoat, only dyed black instead of in its original blue. But, to a close observer, such a coat would seem particularly suspicious. However, being there I went to see the Brazilian minister. He read my letters & told me that if I should go to Brazil he had no doubt I could secure a commission in the Brazilian army, but he had no authority to speak on the matter or to send any one, nor any means to use to that end. Possibly, he said, the consul in N. Y. might render aid. He said that, I am sure, just to get rid of me. He seemed to be actually afraid lest my being in his house might bring a mob on him. (pp. 547-548).

…I went by the old National Hotel for my hand baggage, left there in the morning, & took a street car to the B.&O. Railway station. I knew the city was swarming with detectives, amateur & regular, all stimulated by the enormous rewards offered for every one connected with the murder plot; and, as I got out of the street car, I spotted one of them standing on the side walk & evidently sizing up the people coming to take the train.

Alexander was followed by the detective, but he managed to evade him in the crush of people rushing for the train and make his escape to New York.

I was reminded of Alexander’s experiences while reading Caroline Janney’s fine new book Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army after Appomattox published by University of North Carolina Press (2021).

This is an interesting article. It is a miracle that Lincoln’s assassination did not result in widespread retaliation and death.

Thanks for reading it. When we think of the murder of Lincoln it is always important to look at its impact on public opinion.

Thank you for this fascinating end-of-war piece. It’s been years since I read E.P. Alexander’s Fighting for the Confederacy, and I haven’t yet tackled Caroline Janney’s Ends of War but will soon. The change in the zeitgeist following Lincoln’s assassination was dramatic and complete. Nothing captures it better than Alexander’s experience before and after April 14th.

Thanks.

A lot to unpack in this excellent article: the plight of desperate men following the defeat of their Cause; the revelation of Lincoln’s assassination and immediate responses to the news; the curious bond of West Point alumni, seemingly rising even above national affiliation…

Many of the former Rebel soldiers who fled to Brazil (known as Confederados) settled in the State of Sao Paulo, where they established the town of Americana. Their descendants may be found in Brazil to this day.

Interesting reading, because I knew nothing about the problems faced by former Confederate officers post surrender.

Thanks

It’s been some years since I read Fighting For the Confederacy, and I’d forgotten that Alexander had these conversations with former opponents immediately following the surrender. So thank you for bringing this once again to our attention! I’ve always admired Alexander, but I’ve never quite understood why he urged Lee to forego surrender and seek other avenues for continuing the war.

thanks, great post … along with Grant’s, Alexander’s is my other favorite memoir … written, i believe, at the request of his children, for his children while he was doing railwork in Central America… so, none of the bluster and self-promotion one reads in other remembrances.