The 111th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Lookout Mountain

At three o’clock in the morning on Tuesday November 24, 1863, having received his orders from Union XII Corps commander Major General Joseph Hooker, Brigadier General John Geary sent the men of his Second Division forward. Before them, Lookout Mountain loomed.

Photo: wikipedia.org

The Division’s Second Brigade, under the command of Colonel George A. Cobham Jr., the brigade consisted of the 29th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, the 109th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, and the 111th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. They were to lead the assault.

Upon reaching Lookout Creek, the brigade was joined by Brigadier General Walter C. Whitaker’s brigade of the Union IV Corps. Together, the force crossed Lookout Creek, and Cobham’s brigade assumed position on the right of the Union line, with Whitaker’s brigade making up a second line, its right on the center of Cobham’s line. (1)

The weather that day was cold and damp. Low clouds and an accompanying mist hung in the air, shrouding the mountain, and making it hard to see the movements of enemy troops.

At 9:00 a.m., a charge began along the entire line and the charge continued for three miles in the fog. The center and right of the line advanced about a mile before they encountered the first enemy pickets who were quickly driven in. Soon thereafter, the Federals met their first real resistance.

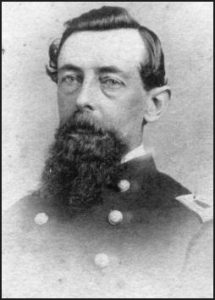

Photo: from “Soldier’s True” by J. Richards Boyle

The 111th, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas M. Walker, made up the center-right of the brigade, with the 29th Pennsylvania on their right. Across from them was a brigade of Mississippians under the command of Brigadier General Edward C. Walthall. “The 111th charged the Mississippians while the 29th swept around their flank. In five minutes, a wall of flaming steel surrounded the besieged line, and within fifteen minutes the enemy threw down their arms.” (2)

Due to the slope of the mountain, the Second Brigade made its way forward by constantly moving to the right, corkscrewing its way upwards. This caused the brigade to get out ahead of the rest of the division, making quicker work towards the crest, preventing the enemy from attacking its flank. This movement also let the division outflank this part of the Confederate line, leaving the Rebel rifle-pits and breastworks completely indefensible.

Once past the captured entrenchments, the 111th, with the 29th at its side, came around the point of the mountain, bringing the Craven farm into sight. The farm sat on a small shelf of land not too far from the top of the mountain. Confederates had set up a defense on the plateau, centered around the Craven house. It consisted of rifle pits and stone walls, as well as being supported by artillery. Other troops assumed position in line form the palisade on the left, across the farm and down the slope to the right. Cobham, and his brigade attacked the Confederate defenders by the flank, from near the shoulder of the shelf, while Colonel William Grose’s brigade of General Charles Cruft’s Division of the Union IV Corps, Army of the Cumberland, made a direct assault up the slope, together they charged the position. To help blunt the attack, Confederates at the top of the mountain tried rolling shells and grenades from above, but to little effect. As the confederate defense began to falter, the men were pulled out, and fell back around the eastern side of the mountain. Within minutes the Craven house, and the area around it, were in Union hands. The Confederates then established a line of works, several hundred yards beyond the Craven house, to prevent any further union advance.

By 2 p.m., most of the fighting was over, though firing continued into the evening, neither side attempted to attack the other. Cobham’s flag flew from the highest point of the mountain gained during the day. (3) The 111th remained on the line until 10 p.m. at which time they were relieved by fresh troops. General Hooker believed that once his men had possession of the western slope, and shoulder of the mountain, the Confederate position upon the crest would have to be evacuated, and he did not have his men try to advance any further. That night, the Confederates evacuated the crest of the mountain to strengthen their position on Missionary Ridge.

The 111th’s loses were light: one enlisted killed, seven wounded, and two officers wounded. (4) In 1890, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania erected a monument to the 111th at Lookout Mountain that featured bronze bas relief of the action of the battle. Like several other monuments on that part of the battlefield, it was embedded in the side of the palisades along the trail between the Craven house and the top of the mountain, the final position of the regiment during the battle.

- OR 31, pt. 2, 424

2.Boyle, John Richards, Soldiers True: The Story of the One Hundred and Eleventh Regiment Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers and the Campaigns in the War for the Union. Creative Media Partners, LLC, 2015, 177.

3. OR 31, pt. 2, 397

4. OR 31, pt. 2, 83

Good story. Having been to Lookout Mountain a few years ago, I marvel at the ability of the Geary Division to ascend and fight in that location.

Nice piece. The men of the 111th Pa had a great deal of trust in Walker, at least that’s what I see from 1862. That seems to be demonstrated here as well.