2nd Maine veteran funded the monument to his regiment

A veteran’s desire to immortalize the 2nd Maine Infantry Regiment in bronze and stone finally bore fruit more than a century after the outfit left central Maine to help save the Union.

Born to lumberman Waldo Treat Peirce and his wife, Hannah Jane Peirce, in Bangor in 1837, Luther Hills Peirce grew up on Harlow Street next to where the Bangor Public Library stands today. Graduating from Yale in 1858, he returned to Bangor and became involved in business.

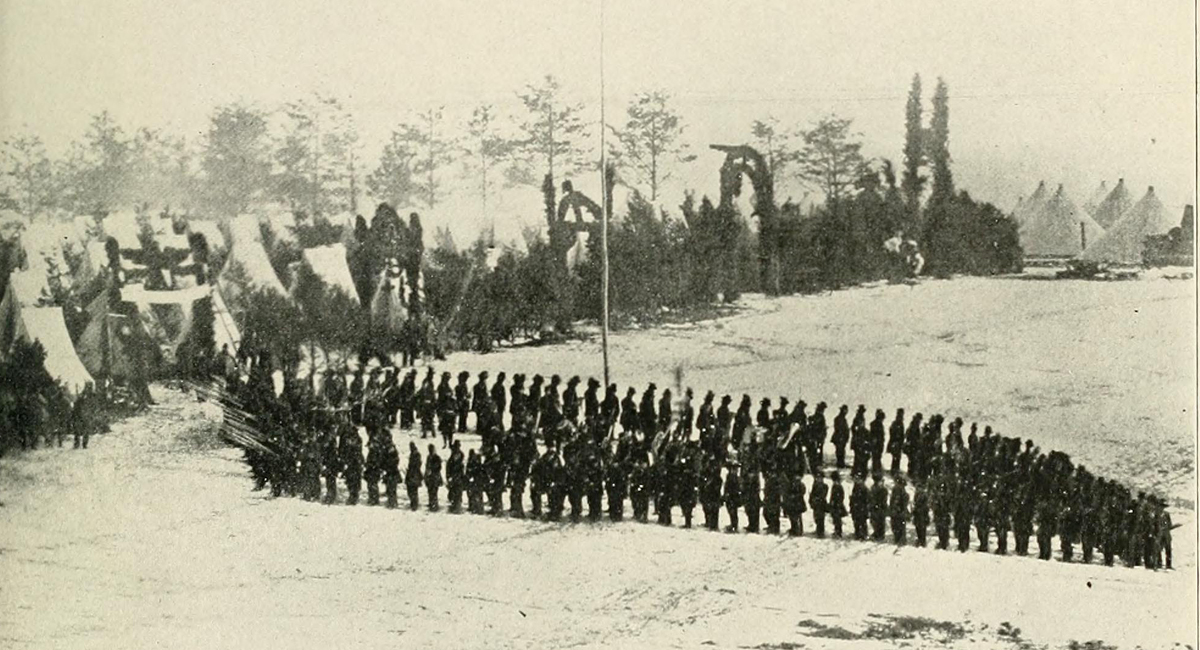

History would have forgotten him except for the Civil War. Directed by the War Department to create 10 infantry regiments in April 1861, Maine pulled together existing militia companies and new recruits to fill out the 2nd Maine Infantry Regiment. Commanded by Col. Charles D. Jameson, it coalesced at Bangor that spring.

Familiar with logistics, Peirce mustered as the regiment’s quartermaster sergeant on May 2 and fought at First Manassas. Shifting to the regular army, he became a captain (and a brevet lieutenant colonel) before resigning on January 1, 1868.

Afterwards Peirce moved to Chicago and made money investing in real estate. Sometime during the early 20th century he attended a 2nd Maine reunion in Bangor and shared with comrades his desired regimental monument: “a mammoth granite tent” occupied by statues of Jameson, Charles W. Roberts, and George C. Varney (who had all commanded the regiment), “the field officers, being grouped about.”

That version did not fly.

Peirce provided with “Clause Eleven” in his will the funds to erect a 2nd Maine monument at Mount Hope Cemetery on State Street in Bangor and to install a Second Maine Regiment Memorial Gate and Fence along the cemetery’s Mount Hope Avenue boundary.

Peirce was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery after dying in Chicago on October 20, 1915. He generously bequeathed $100,000 apiece to the Bangor Public Library and Eastern Maine General Hospital, funded the pedestrian Norumbega Parkway connecting two downtown Bangor streets, and paid for the The Last Drive, a monument depicting three bronze “river drivers,” lumbermen who rafted logs down Maine rivers in spring.

Erected in 1935 and also called the Peirce Memorial, that monument stands beside the Bangor library.

With the Civil War’s centennial looming on the horizon, the five-member executive committee of the Mount Hope Cemetery Corporation (which has run the cemetery since its 1834 inception) voted on June 16, 1960 “to accept the bequest under Clause Eleven.” The committee commissioned the officially titled “Luther H. Peirce Memorial to the Second Maine Regiment of Volunteers.”

Peirce, of course, had no say in choosing the monument’s sculptor, Owen Vernon Shaffer Jr. Born in January 1928 in Princeton, Illinois, he was as an art professor at Olivet College (Michigan) and Beloit College (Wisconsin) in the 1950s and directed the Wright Art Center in Beloit from 1955 to 1961.

Coincidentally with the Civil War’s centennial, Shaffer took up sculpting full time in 1961, and the 2nd Maine memorial was among the first complex outdoor projects in which he would specialize. Charles F. Bragg II, the Mount Hope Cemetery Corporation’s president, already knew Shaffer, possibly from his time spent in Castine, Maine. Bragg talked with the sculptor, and the MHCC’s executive committee approved his monument design in December 1961.

Shaffer created a bronze statue for a contracted $6,500, and the MHCC contracted separately for the project’s remaining components. Supervised by Mount Hope Cemetery Superintendent F. Stanley Howatt, on-site construction took place in 1963.

Backers unveiled the 2nd Maine’s monument on Tuesday, October 30, 1963. No North Carolina-at-Gettysburg monument with its larger-than-life soldiers was this unique statue, which at first sight likely evoked the question, “What is it?”

Shaffer utilized a white granite wall, eight feet wide and 14 feet tall, to which he mounted a bronze sculpture approximately 15 feet tall. “A semi-circular native field stone wall sets the memorial off” from its surroundings, the Bangor Daily News noted, and a concrete walk led to the memorial from Main Avenue, the cemetery’s entrance road.

“I tried in this sculpture not to design another heroic war memorial,” Shaffer stated — and he certainly accomplished that goal. The 2nd Maine’s monument contrasts starkly with the monoliths, sculpted granite blocks, and stirring statues appearing on distant battlefields and with the 140-plus Civil War monuments found elsewhere in Maine.

Its massive bronze wings spread in flight, an angel rises heavenward, its face invisible within a head-covering hood. The angel securely grasps a soldier’s wounded or lifeless body; his eyes closed and his head and shoulders resting against the angel’s lower left wing, the soldier dangles his left arm and both legs.

While eschewing traditional design, “at the same time [I] wanted to show that heroism existed[,] but not without pain. The face and the figure show pain and yet the wings express glory. I hope I succeeded,” Shaffer said.

The sculpture’s placement in the granite block’s upper half depicts ascent, not descent, as if the Death Angel carries a stalwart hero’s soul to meet God. There is a sense of ultimate sacrifice, that the soldier is not forgotten in death.

Inscribed in the granite wall below the soldier’s left foot is the phrase, “Not Painlessly Doth God Recast And Mould Anew The Nation,” taken from the first verse of Ein Feste Burg ist unser Gott (also called Luther’s Hymn), an anti-slavery poem written by John Greenleaf Whittier.

Inscribed below the poem is the 2nd Maine’s “Battle Record” dating from July 1861 to May 1863: Bull Run, Yorktown, Hanover Court House, Gaines Mill, Malvern Hill, Second Bull Run, Antietam, Shepherdstown Ford, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville.

Located three miles from downtown Bangor, Mount Hope Cemetery is not a tourist destination, despite the presence of Vice President Hannibal Hamlin and many lesser-known Civil War stalwarts. After parking in the designated Main Avenue spaces opposite the 2nd Maine monument, people often walk the cemetery’s paved, tree-shaded streets; for such recreationists, the 2nd Maine monument is only a visual backdrop to fresh-air exercise.

Perhaps Luther Hills Peirce should have sited his 2nd Maine monument at Manassas, near where his comrades dueled with Virginia infantry on July 21, 1861. But he insisted on Bangor and a site in the cemetery where so many 2nd Maine boys lie.

Unfortunately the monument draws little attention; not even the Bangor School Departments sends students to view the monument and learn the 2nd Maine Infantry’s history written in blood, sweat, and gore.

Luther Hills Peirce could not foresee the time when his regiment would be all but forgotten by Mainers.

Sources: Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine for 1861, Appendix D, (Augusta, Maine, 1862), p. 61; Index of Names and Subjects of General Orders, Quartermaster General’s Office, 1867 (Washington, D.C., 1868), p. 4; Memorial Unveiled to Men of Second Maine Regiment, Bangor Daily News, Thursday, November 1, 1963; Mount Hope Cemetery Corporation, Memorial to the Second Maine Regiment of volunteers in the Civil War, (Bangor, Maine, 1968); Trudy Irene Scee, Mount Hope Cemetery of Bangor, Maine: The Complete History (Charleston, SC, 2012), pp. 188-190

That’s one of my favorite Civil War monuments.