The “Emerging Civil War Series” Series: Passing Through the Fire

Writing Joshua Chamberlain’s Bio Involved a Reporter’s Approach

Writing Joshua Chamberlain’s Bio Involved a Reporter’s Approach

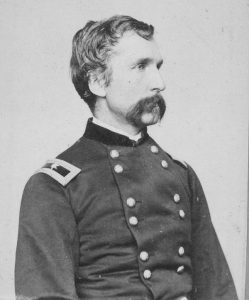

When Chris Mackowski invited me in February 2019 to write a Joshua L. Chamberlain biography for Emerging Civil War Series, I had already worked 33 years as a newspaper reporter and editor, covering the violent (murders and auto accidents) to the mundane (grand openings, school programs, and political windbags).

Chamberlain would be my first biography. How do you write a book-length biography?

Ultimately I approached it like writing a newspaper article on deadline. Chris cited a specific month and year for getting the first draft into his hands. Checking the 2019 calendar, I realized that doing research that spring, summer, and fall would position me to write in winter 2019-2020.

A reporter’s job basically involves information gathering and dissemination. When on a newspaper assignment, you start with what you know (if anything) and build on that.

After listing what I knew about Chamberlain and coalescing my limited JLC library onto one shelf, I got Alice Rains Trulock’s Chamberlain epic, In the Hands of Providence. Realizing that Trulock was thoroughly pro-JLC, I read her book to learn Journalism 101’s basic “who, what, when, where, and how.”

Trulock certainly conveyed all that information. Her extensive footnotes led to many sources and broadened my JLC knowledge. But I needed to learn much more, especially to add to Chamberlain’s tale a sixth element: “why.”

Research efforts — most likely an email — introduced me to Steve Garrett, the Joshua L. Chamberlain Civil War Round Table president and a Pejepscot History Center volunteer in Brunswick. Steve literally opened the research door to the PHC’s incredible JLC archives (print and photographic), a treasure trove as valuable to a historian as a knowledgeable inside source willing to speak off the record is to a journalist.

We had only landlines and no Internet when I started with the Bangor Daily News a few centuries back, and news reporting often required travel, particularly difficult during a Maine winter. The Chamberlain research took me physically far afield, but the Internet enhanced time spent researching and communicating.

I dug into the past online, downloaded regimental and V Corps histories and letters and memoirs, found period material referring to Chamberlain’s on-scene or nearby presence, and communicated with people who pointed at other sources. Having read many of their books, I can only imagine how Bruce Catton and Shelby Foote would have relished the Internet’s research capabilities.

As the Pejepscot History Center did with printed records, so did Susan Natale and her all-things Chamberlain website, www.joshualawrencechamberlain.com, provide extensive information electronically. She has gathered on one site material scattered physically across multiple locations; her website and the PHC’s archives saved a lot of time, effort, and frustration.

So did the staffers at the Maine State Archives and Special Collections, Raymond H. Fogler Library, University of Maine.

In the good ol’ days, reporters practiced neutrality (hopefully) when writing about controversy, and a good editor caught and cut personal opinion slanted as fact. Passing Through the Fire would not personify a JLC cheerleading squad, all Chamberlain fluff and no other stuff. After researching the Gettysburg criticisms raised by Ellis Spear and other 20th Maine soldiers and the recent contretemps involving Chamberlain’s Petersburg wounding site, I added those points to the appropriate chapters.

In the winter 1865 letters written to his parents, Chamberlain let slip the “why” that I sought. Explaining his impolitic decision to rejoin the army (and unintentionally add to his military glory), he cited his unquestionable patriotism and revealed his well-concealed ego; now a general, he sought division command.

He simply wanted more.

A good reporter looks for visuals to enhance a news article. Like all Emerging Civil War Series’ titles, Passing Through the Fire would include illustrations, photos, and maps, cumulatively far more visuals than a newspaper can publish for a single story — unless it’s on a 9/11 scale.

Dividing the JLC bio’s imagery into what was “shot” long ago and what could be photographed today, I sought the “past” online and photographed the “present” in 2019 and early 2020. Some images existed from my prior visits to Appomattox Courthouse, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg.

Edward Alexander provided the excellent maps and spent a day guiding my son, Chris, and me on a JLC tour covering late March to April 1, 1865. I lugged my camera. Not knowing which scenes would make the “cut,” I snapped away; a newspaper reporter covering fast-breaking on-the-scene news does the same, because you never know which particular image will catch that “gotcha” moment.

And the Internet took me farther afield to find wartime photos.

As do all ECWS authors, I converted the collected jpegs and PNGs to 300-dpi black-and-white Tifs. Photoshop and I already had a great working relationship; I learned photo processing a few decades ago, and this part of the JLC project was perhaps the easiest for me.

The project shifted to writing in October 2019 as winter crept over the northern Maine horizon. Organizing my writing time, I balanced the JLC chapters with freelance assignments (I’m still covering Maine news) and wrote furiously from October through January.

Newspaper reporting’s similar: You could be handling multiple breaking stories while developing a long-term, issue-oriented article. Passing Through the Fire was my long-term assignment that winter.

As with a difficult or complex news article, the book involved considerable tweaking and backfilling. And as with any news article, the book required editing. I am grateful to Chris Mackowski for his calm demeanor and patient guiding hand throughout this project. He’s an excellent editor — and I’ve known a few newsroom editors who inspired only fear and hatred and then the subsequent wild barroom celebrations when those people were fired.

I took the book’s last Maine-located photos on March 11, 2020 and heard while en route home that the World Health Organization’s director had declared Covid-19 a worldwide pandemic. By then Passing Through the Fire was into its second rewrite (others would follow).

Afterward, as with a newspaper article, the book awaited publishing.

You can write all the news articles you’re assigned, but they matter not until splashed across the newspaper’s pages. The same with an ECWS book: not until it’s published does all that work become reality.

We all know the thrill of holding that first copy of our ECWS title; a reporter feels the same when seeing that byline beneath a headline. And if you’ve ever flipped through your new ECWS book’s pages while smelling that fresh ink, you’ve experienced a newspaper moment: the smell of ink and paper hot off the press.

————

Passing Through the Fire: Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain in the Civil War

by Brian F. Swartz

Savas Beatie, 2021

Click here to read more about the book, including a book description, reviews, and author bio.