Yellowhammers and Environmentalism: Following Law’s Alabama Brigade to Gettysburg (part four)

Read the first parts of this story here.

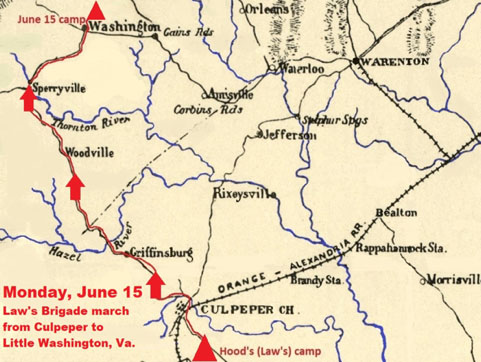

Part 4 – Law’s Alabama Brigade on the move from Culpepper to Little Washington, Virginia.

At 5 a.m. on Monday, June 15, Evander Law’s Brigade of 2,000 Alabama “Yellowhammers” moved out of Culpeper with James Longstreet’s massive column, north-west, towards the Shenandoah Valley. Throughout the day the column would march 50 minutes and halt for 10. There would be a one-hour rest at noon. Following their same route on modern U.S. Route 522, the old Sperryville Pike, Joe Loehle and I moved towards the majesty of the iconic Blue Ridge.

We would often look to see where the old roadbed would deviate from the modern road. To accommodate the speed of the automobile old roads where straightened, and cuts and fills implemented to level-out the infrastructure from the traditional hilly, winding, paths of the horse and wagon past. Thinking of the roads of the earlier period triggered a plethora of thoughts on the subject – private ownership of roads versus government, revenue, macadamization, costs of operation, taxes for improvement, erosion, fencing, bridges, and overall, what did the it look like?

Law’s Alabamians crossed the Hazel River at 3 p.m. on the 15th and then moved on to Woodville and then Sperryville. Crossing the Hazel River Joe and I soon entered Rappahannock County – a favorite in the Old Dominion. There was not a single stoplight in the county. No commercial or residential sprawl existed in the extremely pristine area. It was a relief to see better stewardship and smarter growth. It was my understanding that in the late 1960’s educated, and pedigreed, “hippies” began moving into Rappahannock County and became politically active in protecting the area from the impending sprawl from the rising Washington DC commuting area.

We continued to the quaint town of Sperryville, pushed up against The Blue Ridge, on the Thornton River. Sperryville was a place where you wanted to spend more time. It felt like Virginia – not the “anywhere USA” feel we had seen along Fredericksburg’s/Spotsylvania’s Virginia Route 3 corridor. Sperryville was a nice alternative from the norm of northern Virginia. In Rappahannock County there was “a sense of place”. Interestingly, a little house in Sperryville had been the Virginia headquarters for 2000 Presidential Green Party candidate, Ralph Nadar; appropriate to be in the little town, surrounded by greenspace.

This haj into vanishing rural Virginia caused me to think further of the future of greenspace, agriculture, etcetera. It made me think about conservation, its interpretation, and Conservative politics and philosophy – was there any kinship? Could the Green political element ever work with the politically Right-leaning conservationists that exist in the vein of Teddy Roosevelt? Later I would begin to study conservative-intellectualism some, as a curiosity, and came across the rare Conservative academic intellectual, Sir Roger Scruton, who professed for decades on Conservatism and conservation, he being vocally anti-sprawl. Scruton was a refreshing discovery amongst the perceived political right. Ironically, Roger Scruton was a resident of Rappahannock County in the early 2000’s.

In the Sperryville area there are a couple of iconic grey Virginia state roadside markers that mention where elements of John Pope’s Federal “Army of Virginia” had fought and occupied in the summer of 1862. These state markers are a small example attesting to the layers of Civil War history in the area.

The columns of Law’s sun-blistered brigade moved into Sperryville, then turned right, or east, and away from The Blue Ridge. At 5pm they crossed the Thornton River. The worn Yellowhammers marched 6 more miles before going into bivouac in the area of Little Washington (or Washington), Virginia on the evening of June 15.

Private P. Turner Vaughn, of Company C, 4th Alabama, said of the blistering march, “The day was excessively warm. I have seen more men faint today than ever before. It is said several have died.” Another Rebel said of their corps commander, “Gen. Longstreet is losing too many men by forced marches.”

One of Hood’s Confederates wrote a brutal account of the June 15 march to Little Washington: “[W]e made a distance of twenty miles, under the hottest sun we have ever yet sweltered. To give you an idea of the intense heat of the sun, I will state that we marched through old fields, almost entirely empty of timber, a cloudless, and it seemed brazen sky, by its convex form reflecting the concentrated rays of a burning sun. For hours not a breath of air stirring to cool our fevered brows, clouds of suffocating dust rising, blinding and stifling the men, and the scarcity of good water added greatly to the soldiers’ suffering. Several men died from the intense heat . . . .”

Thinking about this account makes me wonder about the cyclical nature of history; it is not simply just “old”, but constant. When you research temperatures in Northern Virginia during the Civil War you see that they were generally cooler than in more recent times – an interesting perspective to contemplate between now and then.

Fourth Alabama Adjutant, Robert T. Coles, said, “Our first days march was a record one. We went into camp that night in the vicinity of Little Washington, in Rappahannock County, near a beautiful spring, the men were almost completely exhausted.”

A Rebel in Hood’s Division said on June 16, “Last night the soldier needed no rocking to put him to sleep, sweet, sound, oblivious sleep, in the open fields, with the rich, waving, luxuriant clover for a bed.”

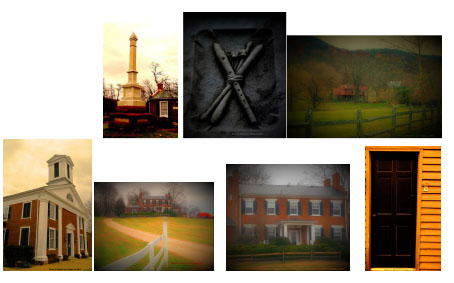

Arriving in Little Washington Joe and I witnessed another Virginia gem – old buildings, a rural setting, peaceful, quiet – and another area where making connections with history was easier because the space had not been compromised yet. I have dreams of living in Little Washington someday. We wanted to stay longer, but we couldn’t — that was a theme on this trip.

At 8:30pm on June 15 General Lee wrote to First Corps commander Longstreet about future movements of his divisions, “Should nothing render it inadvisable within your knowledge, I wish you would advance Hood by the road to Barbee’s Crossroads, &c., to Markham, as arranged today. Your reserve artillery, trains, &c., may be sent, if you think proper, by Chester Gap. Let McLaws and Pickett follow you as rapidly as they can, and should the roads or other circumstances make it advantageous that they should proceed to Front Royal, give them the proper directions accordingly. You can threaten as much as you please an attack upon the enemy’s right flank, so as to throw them back across the Potomac, but advance as rapidly as you can with propriety.”

The welcomed return of Rob Hodge!

I love Route 522 and going through Sperryville! Thanks for the extra history that I will keep in mind on the drive. If you need an excuse (other than history to stop in Sperryville), the Rappahannock Pizza Kitchen is a small, local restaurant with great flavors. 🙂

Enjoyed read about E. M. LAW. After reading the blog I took a short drive to Oak Hill Cemetary and visited the family plot of Major General Law.. The Cemetary is located in Bartow Florida which is named for Col. Francis Bartow. He was killed at First Manassas.