Civil War Myth-busting: Did General Lee inherit a genetic marker that made him more aggressive on the battlefield?

If Lee wasn’t a warmonger, why was he so aggressive on the battlefield? One historian suggests that this combative behavior was passed down through his father’s bloodline.[1] Aggression, though, isn’t exactly inherited. Today’s geneticists acknowledge that heredity “may predispose” an individual “towards becoming an aggressive person.”[2] That said, scientists also “stress that . . . environmental factors play a crucial role in determining whether or not that predisposition will actually be expressed . . . .”[3] Let’s bust a myth!

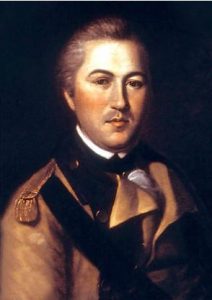

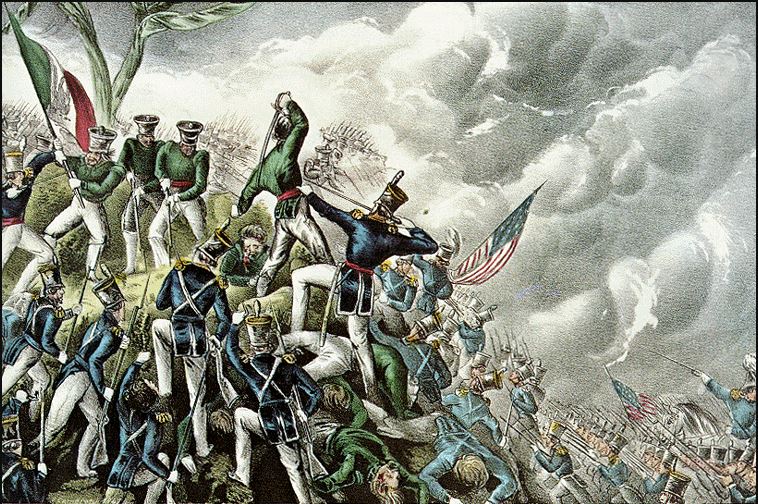

The Lees functioned within a violent professional environment. That’s a given. So, showing aggression to a certain extent was within context. Lieutenant Colonel Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee commanded a legion of cavalry and infantry in the American Revolution. During the Mexican War, Captain Robert Lee served on Major General Winfield Scott’s staff. Many times in their respective billets their commanders directed them to reconnoiter. This action required an aggressive response—time was paramount; speed was critical.

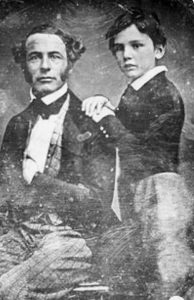

Both Lees executed their tactical tasks quite well. This was because reconnoitering played to their physical and intellectual strengths. Harry was considered little at 5’6″ or 5’7″. His contemporaries described him as “light and agile.”[1] No matter, Light-Horse used his smaller size, high energy, and wits to his advantage. He relied less on brawn and more on cunning calculation, speed, activity, and mobility.[2] Robert inherited his athletic build from his mother’s side or a Lee uncle. He stood at 5’10 ½” and weighed about 145–150. Though larger than his father, he possessed the same hallmark traits as Harry. Captain Lee showed quick thinking and displayed incredible stamina, determined drive, and courage in the Mexican War.[4]

Let’s briefly turn to the Civil War. General Lee exhibited those same qualities: tenacity, vitality, and bravery. He at the same time aggressively used his army on the battlefield. His exploitation of offensive tactics, however, was part of his strategy. He formulated this idea from a professional belief, not a personal one. In other words, he wasn’t employing offensive tactics because of an aggressive genetic marker. This brings us back to the father and son comparison.

It’s important to distinguish between a violent individual and use of the offensive. Light-Horse Harry was not only aggressive in battle; he embraced a vicious nature. Biographer Charles Royster aptly described him. “As a professional soldier, [Henry] Lee was devoted to violence, no matter with how much skill and order he might grace killing.”[5] His Legion participated in the insurgent and civil war aspects of the revolution. His men used unconventional tactics. The combat was extremely violent. At Stony Point in 1779, he hung a deserter. He then chopped his head off and sent it to General George Washington’s Headquarters “to be used as warning to the troops.”[6] In February 1781, his legion dressed as British cavalrymen and ambushed a 300 man loyalist battalion. Light-Horse’s men “sabred [sic], bayoneted, and shot to death about one hundred” of them. Another two hundred were wounded. Harry Lee likewise made decisions that intentionally harmed colonial civilians, like taking all their food.[7]

The youngest Lee son reacted to warfare quite differently from his father. Sure, he was a hard-charger in battle, but he restrained himself. In fact, in his thirty-six years as a professional soldier, there exists no record indicating that he personally killed one of his adversaries.[8] That’s pretty incredible considering the amount of battles he participated in. His involvement, though, was enough for him to see the hideousness of war. He wrote to a relative after his first open engagement during the Mexican War: “You have no idea what a horrible sight a field of battle is.”[9]

General Robert Lee despised the brutality of war so much he made every effort to diminish its effects in the Civil War. He even created policy that kept the violence away from Northern civilians. During the Gettysburg Campaign, he released General Order 72. The directive provided strict orders for procuring supplies while in enemy territory. His first regulation stated: “No private property shall be injured or destroyed . . . .” He then designated the heads of his commissary, quartermaster, ordnance, and medical departments could obtain goods. Anyone who violated his directives would be promptly and swiftly punished.[10] From the beginning to the end of the war, he sought only to inflict violence against the Union armies in a conventional manner on the battlefield.

In fact, talk of unconventional tactics was shunned at General Lee’s headquarters. He disapproved of insurgents. He viewed them as undisciplined. He felt the benefits of guerrilla warfare didn’t outweigh the destructive results. Homes burned; civilians murdered.[11] Around the time of Appomattox, an officer asked him to continue the war using unconventional methods. He refused. Lee replied the “country would be full of lawless bands in every part, & a state of society would ensue from which it would take the country years to recover.”[12] It was time for the nations to heal.

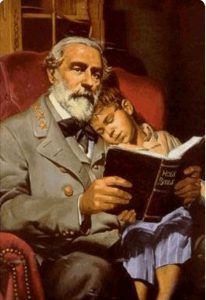

Like many commanders, Robert Lee lived two distinct lives. He was an aggressive soldier on the one hand. It could even be argued that as a general he excessively employed offensive tactics. Even so, he wasn’t a violent man. Those who met him described him as kind and gentle.[13] He dearly loved his family. He had a compassionate way with animals. He enjoyed a natural connection to children. He seemed to put them at ease. He had many run-ins with youngsters. Some occurred while he served as President of Washington College. On one occasion, he was attending a college commencement when a “little fellow” stole away from his mother, got up on the platform, and sat down on Lee’s feet! This once fearless general “remained in one position for a long time, and put himself to considerable inconvenience and discomfort” because he was afraid of waking a child.[14] What a contrast!

The best way to understand how a person can exhibit aggressiveness and kindness is to befriend combat veterans or read about them. Over time, you’ll find out what branch they were with, where they served, and what battles they fought in. You should at the same time get to know them as civilians. Ask them what kind of job they did after the war? How many kids they have? What are their hobbies? What kind of pets do they have? You will probably discover that these once great warriors are now gentle giants.[15]

[1] Royster, 25–7.

[2] Ibid., 26.

[1] Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee through His Private Letters (New York: Viking, 2007), 323–24. Though I disagree with Pryor’s assessment on this subject and others, this is a good biography. I have a hardback copy and a digital one.

[2] Barbara Krahé, The Social Psychology of Aggression, 2nd ed. (New York: Psychology Press, 2013), 33. See also, Anastasi.

[3] Krahé, 33.

[4] Charles Royster, Light-Horse Harry Lee and the Legacy of the American Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1981), 26. Mason, 49.

[5] Royster, 74.

[6] Thomas Boyd, Light-Horse Harry Lee (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1931), 39 and Royster, 36–9. General George Washington warned Lee to “practice with caution” hanging deserters. The General too asked Lee not to commit such a brutal act again. See George Washington to Major Henry Lee, July 10, 1779. George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, vol. 15, May 6, 1779 – July 28, 1779, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1936), 399.

[7] Royster, 53.

[8] He served on Scott’s staff as an engineer during the Mexican War. His assignments included reconnoitering and deploying batteries. For Mexican War, Douglas Freeman, R. E. Lee, vol. 1, 218–87 and “‘We Are Our Own Trumpeters,’ Robert E. Lee Describes Winfield Scott’s Campaign to Mexico City,” ed. Gary Gallagher. Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 95, no. 3 (July 1987): 363–75.

[9] Douglas Freeman, R. E. Lee, vol. 1, 246.

[10] R. E. Lee, General Orders No. 72, June 21, 1863, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), Ser. 1, vol. 27, pt. 3, 912–13. See also, R. E. Lee to Davis, Headquarters, June 23, 1863, Ibid., vol. 27, pt. 2, 298.

[11] Anthony James Joes, America and Guerrilla Warfare (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2000).

[12] Chris Mackowski, “Lee and Guerrilla Tactics,” ECW, December 7, 2017.

[13] Robert E. Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (New York: Doubleday, 1904), 158.

[14] John W. Jones, Life and Letters of Gen. Robert Lee: Soldier and Man (New York: Neale, 1906), 465.

[15] List of Illustrations: Light-Horse Harry Lee, National Archives; Battle of Cerro Gordo, http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/cerro-gordo.htm; General R. E. Lee rallies his men, Mort Kunstler; R. E. Lee with his son William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney”, Virginia Historical Society; The Christian General by William Maughan

Thanks JoAnna for this erudite and well researched presentation!

Well written, JoAnna. His gentleness of person and sweetness of disposition was often commented upon, not always favorably. Thus the snide remarks about “Granny” and “Evacuating” Lee. People don’t realize how much an anachronism Lee was in the thrusting, ambitious “new” planter society of the South, many of whom were the leaders of the rebellion. He was bold in strategic conception, his weakness was in reasonable evaluation of resources for tactical implementation. He loved and admired his men beyond logic.

Remarkably, Lee also gave pincushions to any soldier mentioned in a dispatch. The pincushion had little value to a man, but it was a valued by the soldier’s wife or female relative. Lee understood some 100 years before the US Army the value of appealing to the families of soldiers. Nice post. Thanks.

Tom

Some animals are more equal then others….Lee was not as gentle too all according to Owen Robinson , Rachel Cormany and Jakob Hoke citizens of Chambersberg July 1863. All three testified about the great ex-slave/ freedmen droves being pushed back to Richmond under the lash and Command of General Robert E Lee.

It was beneath Lee’s dignity to personally ‘Lash an escaped slave, his position on the institution of slavery and its evils was lukewarm. Slavery in many forms is alive and well in the muslim world, slavery even tho hidden, rears it ugly head in the news from time to to time! Wm. Wilberforce and Sir Isaac Newton would roll in their graves!