The Romney Expedition: A Forgotten Union Victory?

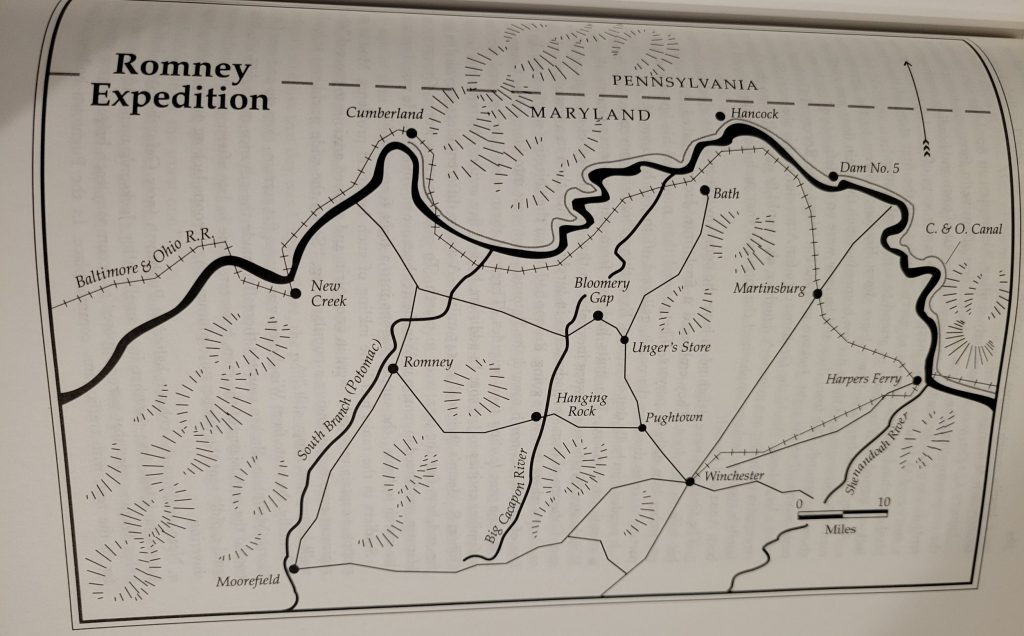

The Romney Expedition pushed Federal troops across the Potomac and out of the larger towns of Bath and Romney. Along with the capture of supplies worth thousands of dollars, the Confederates were poised to set up a defensive and communication chain into western Virginia which could have delayed a future Union advance toward Winchester. However, due to the internal squabbles of the Confederate commanders, Romney was eventually evacuated and the advantages slipped away.

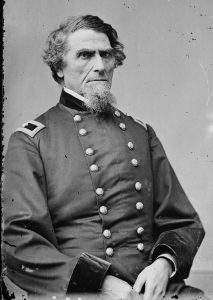

Did you that some Union commanders actually claimed a victory during the Romney Expedition? Not during their retreat to the Potomac, but during their military offensive in Jackson’s rear. General Benjamin F. Kelly submitted the following report, highlighting a skirmish at Hanging Rock Pass:

General: I herewith [e]nclose you Colonel Dunning’s report of the expedition to Blue’s Gap on the 8th [7th] instant.

I am happy to say that the expedition was an entire success. The effect was, as I intended, to divert the attention of General Jackson from Hancock, he supposing that I was moving on Winchester with my whole force, and therefore beat a precipitous retreat from Hancock and fell back on Winchester.

I am happy to say that the troops under my late command evinced on that occasion the same energy and gallantry that have characterized them ever since they have been under my command.

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

B. F. KELLEY, Brigadier-General.[i]

While Jackson looked at the freezing Potomac and lobbed a few shells toward Hancock, Maryland, other Union troops swung south between the Confederate army and Winchester, threatening their rear. Jackson did fall back toward Winchester, temporarily, then continued further west to Romney as the campaign progressed.

Colonel Samuel H. Dunning of the Fifth Ohio Infantry wrote an official report about the skirmish at Hanging Rock Pass, including these details:

General : In obedience to your orders by telegraph, received at these headquarters January 7 [6], directing me to make a detail of six companies from each of the following regiments: Fifth Ohio, Fourth Ohio, Seventh Ohio, First West Virginia, Fourteenth Indiana, and, by special request of Colonel Carroll, six companies of the Eighth Ohio, with one section of Baker’s Parrott guns, Damn’s battery, the Bing-gold Cavalry, the Washington Cavalry, and three companies of the First West Virginia Cavalry. Owing to sickness and large numbers on picket duty, the response was small, and the whole force did not exceed 2,000 men.

The command assembled about 11 p. m., and by 12.30 o’clock the column was in motion for its destination at Blue’s Gap. The fall of snow, with the disagreeable and cold night, rendered it difficult for the troops to march, but by 7 o’clock in the morning we reached a hill within about a mile of the gap. On this hill the Parrott guns were planted, and from it the enemy could be seen preparing to fire the bridge. I then ordered the Fifth Ohio to advance by double-quick. The order was responded to by a shout, and in a few minutes the advance of the regiment was on a bluff near the bridge, and with a few shots compelled the rebel forces to retire from the bridge to the gap. The column vras then ordered to advance rapidly on and over the bridge, and the Fifth Ohio was deployed up the mountain to the left and the Fourth Ohio to the right. A sharp action then ensued, first on the left of the gap and then on the right. Our forces pressed on, driving the enemy from the rocks and trees, behind which they had taken position, and to the top of the mountain to the left they were found in rifle-pits. A charge was ordered, but before bayonets could be fixed the rebels had left their pits and were fleeing down the mountain in haste to the back of the gap. At this time the remaining detachments of infantry pressed through the gap, and the victory was complete. The cavalry was then ordered to charge, which was done promptly, but the enemy had by this time scattered in the mountain, rendering the charge of little avail.

The enemy left behind them two pieces of artillery (6-pounders, one a rifled gun), their caisson, ammunition, wagons, and ten horses; also their tents, camp equipage, provisions, and correspondence. Seven prisoners were taken and 7 dead bodies were found on the field. Not one of my men were either killed or wounded.

I take pleasure in stating to you that our officers and men seemed to vie with each other in the promptness with which they obeyed orders, and all advanced with the bravery of veteran soldiers….

Finding the mill and hotel in the gap were used for soldiers’ quarters, I ordered them to be burned, which was done; but I am sorry to say that some straggling soldiers burned other unoccupied houses on their return march.

The force of the rebels was stated by negroes and citizens at from 800 to 1,000, but their papers show that rations were drawn for 1,800 men.

We marched to the gap, fought the battle, and returned to camp within 15 hours, bringing with us prisoners, cannon, and other captured articles.[ii]

This Union success hampered Jackson’s plans. The only Confederate outpost between Winchester and Romney had been surprised and captured. Whether the Union officers realized it or not, the road east to Winchester lay open to them.[iii]

Then, in one of the odd turn of events that are difficult to explain, the Union force at Hanging Rock simply fell back to Romney. There was no advance on Winchester or further operations in Jackson’s rear. Perhaps the officers through the numerical addition to the defenders at Romney would make a difference if Jackson turned that way. (It didn’t.) Perhaps they were more sensible of the weather and campaign conditions. Maybe they thought there were more Confederates at or arriving at Winchester. Whatever the reason, their sudden retreat left a hollow victory at Hanging Rock.

Although the Union maneuvers and the success at Hanging Rock did not impact the outcome of the campaign, they are an important reminder that successful skirmishes did happen in the mountains or Shenandoah Valley and that not all Union volunteers retreated or lost when they faced Stonewall’s expeditions. A few weeks later, thousands of Union soldiers prepared to march into the Shenandoah Valley from different points. They looked for victory in their Valley Campaign and certainly had not settled on inevitable defeat.

Sometimes, knowing how the story ends in the winter or spring of 1862 makes it easier for the successful moments of the losing side to slip through without much notice. However, these smaller skirmishes were moments of importance to the soldiers who fought there and should be remembered in the larger contexts of the campaigns.

Sources:

[i] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 5. Page 403-404. Accessed via HathiTrust: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077730194&view=1up&seq=419&skin=2021

[ii] Official Records, Series, Volume 5. Page 404-405. Accessed via HathiTrust: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077730194&view=1up&seq=419&skin=2021

[iii] James I. Robertson, Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, (New York, Macmillan, 1997). Pages 309-310.

“Victory was complete.” Great series, Sarah, thank you.

Thanks for reading! I enjoyed putting it together and am waiting for the temperatures to rise a little before I attempt my own trek to Romney. 🙂

Frederick Lander, if he had lived, might have caused Stonewall a lot of problems and altered how the Valley campaign played out. We’ll never know though.

Captain John Keys of the Ringgold Cavalry was ordered by Lander to retake Romney and burn down their bank, courthouse, and jail. When Keys got there he refused to carry out the order. “If I carry out my orders, the way the wind is blowing, the entire town will be consumed. Rather than turn helpless women out of doors, at this time of year, I will disobey this order” (Elwood’s Stories of the Old Ringgold Cavalry, p.88). Actions like this gained much respect for the Ringgold Cavalry in the secessionist-majority town of Romney, and even among their principal antagonists, the McNeill Partisan Rangers.

Thanks for putting this information together Sarah. Deb and I will be in Romney in October.