Book Review: Radical Relationships

Radical Relationships: The Civil War Era Correspondence of Mathilde Franziska Anneke

Radical Relationships: The Civil War Era Correspondence of Mathilde Franziska Anneke

By Alison Clark Efford (Editor), Viktorija Bilic (Editor, Translator)

University of Georgia Press, 2021, $32.95 – softcover

Reviewed by David T. Dixon

One of the great advancements in scholarship during the second half of the twentieth century was the belated effort of historians and other scholars to recognize the expansive roles that women played in the nineteenth century world — not merely as matriarchs of a family unit, but often as key actors in and influencers of historical events. American women like Sacagawea, Harriet Tubman, Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, Harriett Beecher Stowe, Clara Barton, and many others became household names then and remain so today. Thousands of lesser-known but important American women deserve more time in the historical limelight. Mathilde Franziska Anneke’s life story and accomplishments certainly merit closer study.

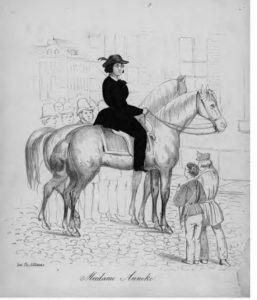

Born in 1817 to wealthy Westphalian nobleman Karl Giesler, Mathilde grew up in a castle, but that idyllic existence ended abruptly as the result of an unhappy marriage at the age of nineteen to a local nobleman who treated her so badly that she was granted a divorce after just one year of matrimony. During her divorce hearings, she published articles in the Kölnische Zeitung and soon became the first outspoken advocate of women’s rights in the German states, developing a wide reputation for oratory and writing skills. Her 1847 essay, Women in Conflict with Society, helped change laws concerning marriage and divorce throughout the German Confederation. She married Fritz Anneke, a former Prussian artillery officer turned radical revolutionary that same year, donning trousers and serving alongside Carl Schurz as Anneke’s adjutants on horseback during the failed revolts of 1849. The Annekes escaped to Switzerland, then emigrated as political refugees to America in late 1849.

Mathilde and Fritz Anneke eventually settled in Milwaukee, where she published Frauen Zeitung, one of the first feminist newspaper in US history and became the most celebrated female German language orator in the country for her activism on women’s rights, abolition, and public education.

Radical Relationships chronicles a small part of Mathilde Anneke’s eventful life through a selection of private letters written during the period from 1859 to 1865 and housed in the ample collection of Anneke manuscripts at the Wisconsin Historical Society. Victorija Bilic, a native of Germany and professor of translation and interpreting studies at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee and Alison Clark Efford, a leading scholar of German American immigration at Marquette University, collaborated to reveal insights into the transnational nature of the US Civil War, the struggle for gender and racial equality, and most provocatively, same sex relationships.

Mathilde developed an intimate friendship with Mary Booth, a talented writer in her own right and the wife of noted abolitionist Sherman Booth, who was prosecuted for raping a fourteen-year-old babysitter. Mathilde and Mary’s relationship intensified when Fritz Anneke left in May 1859 to cover efforts for Sicilian independence for the Wisconsin Free Democrat and Sherman Booth was jailed for his abolitionist activities in 1860. Mathilde Anneke conspired with other radicals to finally spring Booth from prison after eight unsuccessful attempts. In August 1860, Mary Booth, Mathilde Anneke, and their children left for Switzerland, where they hobnobbed with other leading radicals like Ferdinand Lassalle and Emma Herwegh, wrote antislavery tracts, and fell deeply in love. They remained together in Europe for five years.

Mathilde wrote Fritz shortly after their separation to express her innermost feelings. “Dear Fritz, we should never have married. We should have stayed friends, and we may have both led happier lives. And indeed, we love each other more like friends now. We love each other since we are most intimately related through the children we have together. But we do not love each other like lovers who both feel that their desire for each other fills their existence and can only be satisfied by the touch of pure lips when they kiss.”

In 1862, Fritz Anneke returned to Milwaukee to take command as colonel of the 34th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. His pride suffered from the fact that some of his revolutionary contemporaries like Schurz, August Willich, and Franz Sigel became general officers. Mathilde chided her husband in wartime letters for his thirst for public acclaim and his lack of interpersonal skills, which created conflict with peers and superiors and ultimately resulted in his court-marital and dismissal from service in 1863. The angst that Mathilde felt when she considered her duty to her husband in a passionless marriage and their mutual responsibility to their children while having finally found her soulmate in Mary is palpable in these incredible letters.

Mary Booth expressed her love for Mathilde Anneke in 1862: “Pardon me, my Dear, for writing you such a miserable little note saying I was unhappy. I am indeed very happy when I think of your sweet love. It glorifies every even[ing] and illuminates the the darkest midnights. You are the morning-star of my soul, the beautiful auroral glow of my heart, the saintly lilly of my dream, the deep dark rose bud unfolding in my bosom day by day, sweetning my life with your etheriel fragrance—dearest, you are the reality of my dreams, my life, my Love—I have no more sorrow—I have You—My dear and dearest friend— good night .”

Efford’s expert commentary and context, combined with Bilic’s sensitive and painstaking translations, uncover a complex and nuanced view radical women activists during the Civil War era that readers seldom get to experience. The life of Mathilde Anneke cries out for a full-length scholarly biography. One hopes that this unusual collection of translated letters will prompt a scholar interested in immigration history, the transnational aspects of the American Civil War, the early leadership of the women’s suffrage movement, radical abolitionism, and queer history to adopt this challenge and give this accomplished German-American pioneer the recognition she deserves.

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2020).

I’m glad that Mr Dixon has a continuing interest in the peripheral figures in 19th Century history. I would politely suggest that some individuals might remain somewhat peripheral in light of their limited actual impact on that era. Modern scholarly studies will not change that essential fact.

Perhaps not, but the worst they can do is provide appropriate context for what the modern historical consensus considers to be the more pivotal figures. And who knows, it may lead studies in new directions. Labor and social history, as it began to be studied widely in the 1950s and 1960s, was an offshoot of business and industrial history that historians to that point had not considered to be all that important.

Fascinating and interesting. Everyone has a story.

First time I read about Auguste Willich’s wife civil war exploits, I was like — wow!

Thanks for showcasing this book. The 48ers are very interesting, and I’m glad to see this. In hindsight they seem diminished, but in contemporary eyes that was not necessarily the case.