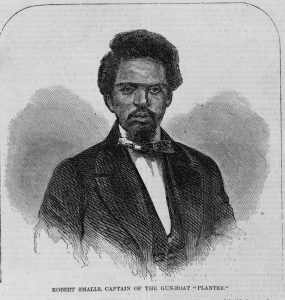

Robert Smalls and the Daring Capture of “Planter”

ECW welcomes guest author Scott L. Mingus, Sr.

At dawn on May 13, 1862, an enslaved eight-man crew, with several family members and other friends onboard, brazenly stole the Confederate gunboat Planter and delivered her past unsuspecting Rebel forts and batteries to the blockading Union Navy. The unprecedented feat garnered headlines in the North and South, and reinforced the notion that the U.S. military should begin using African-Americans in front-line duty. The mastermind of the plot, 23-year-old Robert Smalls, received praise and national recognition that eventually led him to successful business and political careers.

Planter, a wood-burning side-wheel steamer, was 140-feet long with a 50-foot beam. It drew less than four feet of water, making it ideal for shallow operations such as in Charleston Harbor and the river inlets along the Atlantic seaboard. The Confederate government had chartered the cotton ship in 1861 from owner John Ferguson and converted it into a gunboat with a 32-pounder cannon on a pivot and a 24-pounder howitzer. On the evening of May 12, while docked at Cole’s Island, the ship had taken on four additional guns from a decommissioned fortification that now were to be transferred to the Middle Ground Battery at Fort Ripley. These were a banded 42-pounder rifled gun, an 8-inch columbiad (both originally from the Union garrison at Fort Sumter), an 8-inch seacoast howitzer, and another 32-pounder, as well as 200 rounds of ammunition and 20 cords of much-needed firewood. Planter then returned to Charleston and docked at Southern Wharf.[1]

The ship’s officers were Captain Charles J. Relyea, Mate Samuel H. Smith, and Engineer E. Zerich Pitcher. The crew of enslaved Blacks included the pilot, Robert Smalls; engineers John Smalls (no relation) and Alfred Gradine; and crewmen J. Samuel Chisholm, Abraham Allston, Gabriel Turno, Abraham Jackson, and David Jones. Robert Smalls, a fair-skinned enslaved native of Beaufort, SC, had been a wheelman (equivalent to a pilot) in Charleston Harbor for many years. An ardent sailor since his teen years, he had served on Planter since the fall of 1861, piloting it during its use as a transport vessel and harbor guard.[2]

After one of the crew joked about running the vessel out to sea, Smalls started to think about the prospects. The seemingly preposterous idea gained traction in his mind. He warned the crew not to mention stealing the ship, even in jest, and asked them to meet at his quarters above a stable on East Bay Street in Charleston if they were interested in learning more. All but David Jones joined in the endeavor; he swore his secrecy.[3]

The group debated various plans to commandeer the ship and steam it out to the protection of the U.S. Navy. They decided to leave the detailed planning up to Robert Smalls, agreeing to obey him and be ready at a moment’s notice. He hid extra provisions in the hold and waited for an opportune moment to slip away. Finally, after three days of anxious waiting, that chance came. On Monday evening, May 12, the Confederate officers went ashore to spend the night. They planned to return in the morning and take Planter to Fort Ripley for several days. Robert Smalls notified his men that the time was at hand. With the officers’ permission, his wife Hannah and three of her children came on board, as did John Smalls’ wife, child, and sister, and two of the crew’s girlfriends, as long as they departed before curfew. Crew members took them ashore before secretly escorting them to a nearby ship, Etowah.[4]

The Confederates had posted three sentinels within sight of Planter, with another 20 men within hailing distance in case of trouble. About 3 a.m., the crew lit the fires under the boilers. By 3:30 a.m., Planter had her steam up, and the Confederate and South Carolina flags were hoisted. She soon was underway along the bay. First, they picked up the women and children, as well as a steward, William Morrison, from Etowah. Smalls blew Planter’s whistle, as was customary at the Atlantic Wharf before heading out into the harbor. The guards believed this was a routine exercise and paid no special attention to the ship as it headed out into the harbor. Smalls wore the captain’s linen shirt and jacket and characteristic floppy straw hat and copied his mannerisms, aiding in the ruse.[5]

At 4:15 a.m., Planter, fighting the tide, approached Fort Sumter, where Smalls gave the requisite signals, three long shrill blasts of the whistle and a then very quick hiss. Inside the fortifications, the corporal of the guard dutifully reported the ship’s presence to the officer of the day, Captain David G. Fleming. A veteran soldier, he was considered “one of the best and most reliable officers of the garrison.” Neither he nor the corporal found anything unusual in Planter’s passage, believing that she was a guard-boat routinely heading to Morris Island. Onboard, the women cried quietly and prayed for deliverance. Smalls steered the ship on a normal course to defuse any suspicion, despite pleas from some of the men for him to keep a wide berth.[6]

Once they were safely out of range of the Confederate guns, Smalls struck the colors and raised a white bed sheet that his wife had brought and steamed for the blockading fleet some seven miles from the harbor. The USS Onward spotted the oncoming vessel and prepared to fire a gun. However, the white flag became discernable and Captain John F. Nichols boarded Planter, where the men and women were shouting with glee, whistling, singing, and dancing on the deck at their deliverance from slavery. Nichols soon delivered Planter and its daring crew to his superior officer.

Onboard the USS Augusta, Captain Enoch G. Parrott received the “contraband crew” cordially. He assigned Acting Master Watson command of the prize and sent it, with Smalls and his party aboard, 60 miles down the coast to Flag Officer Samuel F. Du Pont at Port Royal. They reached his flagship, Wabash, at 10 p.m. on May 13. Later, the families were taken to Union-held Beaufort. Smalls and the other seven men joined the U.S. Navy, desiring, as he wrote in August, “to serve till the rebellion and slavery are crushed out forever.”[7]

“The Planter is just such a vessel as is needed to navigate the shallow waters between Hilton Head and the adjacent islands,” the Herald reporter believed, “and will prove almost invaluable to the government.” He interviewed Robert Smalls and learned that the prevailing feeling in Charleston was near panic. All women and children had been ordered out of the city in expectation of a Union attack. More importantly, Smalls mentioned that there were seven Confederate steamers in the harbor and only one, Marion, was armed. Provisions were “terribly scarce and dear.” Du Pont and other Federal officers used the detailed information from the intelligent and observant Smalls to capture several Confederate sites along Stono Inlet, which the Union controlled for the rest of the war.[8]

When Planter headed out to sea, it became clear that someone had hijacked it. Maj. Gen. John S. Pemberton sent a message to Robert E. Lee on May 13, informing him of the capture. Confederate authorities soon arrested the three officers on charges of disobedience of a standing order that officers and crews of all government-employed light-draft steamers must remain onboard day and night. The Mercury reporter noted, “The result of this negligence may be only the loss of the guns and of the boat, desirable for transportation. But things of this kind are sometimes of incalculable injury.” He believed the lives and property of the entire Charlestown community were at stake, despite the “trifling” nature of the brazen theft. He urged that the officers be dealt with sternly for their dereliction of duty. Two of them were later convicted at a court-martial, but their verdicts were overturned.[9]

Robert Smalls and his seven comrades each received prize money from the Federal government. His share, as “captain” of the captured vessel, was $1,500. The government also granted him quarter ownership of Planter. Rumors abounded that Confederate authorities in Charleston were offering a reward of $4,000 for the capture and return of Smalls.[10]

He later traveled on furlough to New York City, where he was the guest of honor at a reception at Shiloh Church on October 2. After Smalls entered to extensive applause, he was given a handsome gold medal with a depiction of Planter steaming past Fort Sumter on the obverse. The reverse carried an inscription, “Presented to Robert Smalls by the colored citizens of New York, Oct. 2, 1862, as a token of their regard for his heroism, his love of liberty, and his patriotism.” He, his wife, and small son Robert received “wild and prolonged cheers.”[11]

Abolitionists throughout the North used Smalls’s bold example in their exhortations to use the war to forever end slavery. President Lincoln reportedly considered Smalls’s actions as he contemplated the use of Black troops, a decision that eventually led to the creation of the U.S. Colored Troops and other regiments. Robert Smalls returned to Beaufort after the war, purchased his former master’s house, and raised his family. The staunch Republican served in the South Carolina senate and several terms in Congress before dying on February 23, 1915, at the age of 75.[12]

[1] “Disgusting Treachery and Negligence,” Charleston Mercury, May 14, 1862.

[2] F. G. Ravenel to R. S. Ripley, May 14, 1862, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion [OR] (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922), series 1, vol. XIV, 14-15.

[3] New York Herald, May 15, 1862.

[4] New York Herald, May 15, 1862.

[5] New York Herald, May 15, 1862; F. G. Ravenel to R. S. Ripley, May 14, 1862, OR, vol. XIV, 15.

[6] New York Herald, May 15, 1862; Alfred Rhett to L. D. Walker, May 13, 1862, OR, vol. XIV, 15.

[7] New York Herald, May 15, 1862; “Letter from the Negro Robert Smalls,” Boston Evening Transcript, August 23, 1862.

[8] New York Herald, May 15, 1862.

[9] J. S. Pemberton to R. E. Lee, May 14, 1862, OR, vol. XIV, 13-14; “Disgusting Treachery and Negligence,” Charleston Mercury, May 14, 1862; R. S. Ripley to J. R. Waddy, May 14, 1862, OR, vol. XIV, 14. Zerich Pitcher was found not guilty. Captain Relyea received a sentence of three months in prison and a $500 fine; the first mate had a lesser sentence and fine.

[10] “Complimentary,” The Liberator, October 24, 1862.

[11] “The Hero of the Planter,” Chicago Tribune, October 7, 1862.

[12] “Robert Smalls,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. https://bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/S000502. Accessed Dec. 5, 2021.

in December 2022 when we are detailing “Stories of the Year”, please put this story in the top 5. Amazing and well done.

Thank you, Ed!

thanks Scott … this is a great, but not well-known, Civil War sea story … African Americans — enslaved and free — have a long and distinguished history of seafaring … in fact, going to sea was the only 19th century profession where they could serve alongside their white shipmates in the same jobs — able bodied seaman, pilots and even captains of vessels … African Americans also earned the same pay … Jeffrey Bolster’s BLACK JACKS is a great read for those who want to know more about seagoing African Americans in the age of sail.

Thanks, Mike. I wrote two books on the Underground Railroad here in York County, PA, and mention the critical role formerly enslaved people played in the local economy. One man, William C. Goodridge, became one of the wealthiest men west of the Susquehanna River.

May 1862. The bloody Battle of Shiloh, fought in Tennessee, was still a recent memory. And a bit further south, New Orleans had fallen, and was now under command of Major General Benjamin Butler… the same man who in May 1861 had declared captured Southern enslaved persons as “contrabands of war.” It took a while for Butler’s contraband declaration to catch on: even while General Grant was at Pittsburg Landing, in the weeks prior to Battle of Shiloh, local Southerners were permitted to petition for return of their runaways. But, the U.S. Congress used Benjamin Butler’s declaration as inspiration and incrementally enacted laws granting greater rights and recognition to “escaped slaves that found their way to U.S. Army camps.” By April 1862 it was illegal for the U.S. Army to return escaped Southern slaves to their masters. [See “The Revolutionary Summer of 1862” (2017) by Paul Finkelman https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2017/winter/summer-of-1862 ].

Robert Smalls’ timing in executing his operation was perfect.

Great addition, Mike!

Why this is not a blockbuster movie is beyond me. So many great roles for folks, such a dynamic story–and heroes abound! Please?

That’s a great idea, Meg!

Recently, underwater archaeologists discovered a wreck, believed to be that of Robert Smalls’ steamer, “Planter.” Perhaps 30 miles NE of Charleston, South Carolina, the remains “are stripped down, with only the boilers and some wood still recognizable.” The wreck is covered by 10 feet of water and 15 feet of sand. [See “A Bold Civil War Steamer” (July/AUG 2014) by Eric A. Powell https://www.archaeology.org/issues/139-1407/trenches/2186-civil-war-steamer-planter-discovered ].

Oh, that is interesting, Mike! Thanks for sharing the link! Stay well.

Glad you found the above link worthwhile. The fate of the “Planter” has been of personal interest since conducting research on Civil War activities in and around Pensacola Bay, and reading that a shallow draft steamer named ‘Planter’ arrived at Fort Barrancas wharf in August 1864. The vessel was used by Union Brigadier General Asboth to conduct operations against Rebels ensconced along the Escambia, Yellow and Blackwater Rivers (northeast catchment of Pensacola Bay.) Most notable actions involving Planter (as transport): Milton, Point Pierce, and Marianna. See OR Series 1 Vol.35 (Part 1) pp.442 – 443; and OR (Navy) Series 2 Vol.1 page 180 “Entry for USS Planter: Disposition.”

Apparently, the USS Planter was towed/ cruised back to south Carolina March/ April 1865 in time for the flag-raising ceremony at Fort Sumter [see “The New South” newspaper of Port Royal, South Carolina dated 22 APR 1865 page 1 col.2 https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025760/1865-04-22/ed-1/seq-1/

What an adventure story! Thanks for that. The book “1846” has great detail of Fort Sumter’s occupation, defense, and surrender, but it mentions not in my memory that two of its guns were thusly recaptured. These were a banded 42-pounder rifled gun, an 8-inch columbiad (both originally from the Union garrison at Fort Sumter). I took a commercial boat tour of Charleston harbor and there was no mention of this page in it’s storied history going back to the Revolutionary War. Thanks again.

You are most welcome!

I’m with Meg. The life of Robert Smalls NEEDS to be made into a movie. The man accomplished so much during and after the war and doesn’t get enough attention. Well done, sir!

Thank you, Sheritta! This would indeed be a fascinating movie if ever made.

One of my favorite Civil War accounts. And I’ll echo Meg and Sheritta: this needs to be a movie.

Thank you sharing your research and writing!

Amazing story. Do you know where Smalls’ gold medal is located? That is quite an artifact.

I do not know the current location of the medal, but Smalls had a large family and his descendants likely have it. Some of his family later moved to the Philadelphia area.

Thanks for the update. The engraving was wonderful. Great article!

One of the greatest feats of derring do in the history of warfare. Glad to see the hero lived until 1915.