Fallen Leaders: Did Daniel Chaplin commit death-by-sniper?

After seeing his 1st Maine Heavy Artillery destroyed at Petersburg, Col. Daniel Chaplin “seemed not to care to live after his regiment was gone,” thought Pvt. Joel Brown, Co. I. Two months later the distraught colonel was gone, too, possibly by committing death-by-sniper.

Born in New Brunswick in January 1820, Chaplin grew up in Bridgton, Maine before moving to Bangor in 1841 to clerk at a ship chandlery. He married Susan Davis Gibbs in 1846, and the couple ultimately had five children, their only daughter dying very young.

By 1860 Chaplin was a 40-year-old clerk, literate, apparently well educated, and obviously comfortable with numbers, but not wealthy. The family lived in a blue-collar neighborhood, the married men laborers, teamsters, one a watchmaker and another a “manufacturer of pencil sharpeners.”

In late spring 1861 he mustered as captain, Co. F, 2nd Maine Infantry, fought at First Manassas, made major that September, and, after serving on the Peninsula, returned to Maine in summer 1862 as colonel, 18th Maine Infantry Regiment.

Chaplin viewed his soldiers as humans, not as career-ladder rungs. “His men belonged to the same neighborhood as him,” recalled 1st Lt. Horace Shaw. “He had organized them; he had led them from the forests of Maine. They were his great family.”

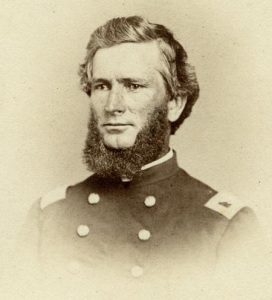

Standing 5-10, with hazel eyes and a dark complexion, Chaplin looked younger than his early 40s when photographed wearing his bird-colonel epaulets. Sporting a full head of gray hair and a thick, but trimmed beard that slipped under and not over his chin, he exuded competence.1

The 18th Maine left Bangor on August 24 and promptly went into the District of Columbia defenses as ax wielders, clearing “more than 3,000 acres of land” to open fields of fire. Redesignated the 1st Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment in January, the unit expanded to 12 companies with 150 men apiece. The work was challenging, but “Chaplin … performed the duty with consummate ability, and brought his men to a high degree of discipline.”

Ulysses S. Grant summoned D.C.-assigned heavy artillery regiments in mid-May 1864 to reinforce the battle-damaged Army of the Potomac. Under Brig. Gen. Robert O. Tyler, the regiments left Washington by ship on May 15 and disembarked at Belle Plain.

Tyler fought Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s combat veterans at Harris Farm on May 19. After recapturing a wagon train, the 1st MHA and other heavy artillery regiments chased the retreating Southerners at the double quick “through a piece of woods—I judge a half mile,” recalled Pvt. George W. Madox of Co. L.

“Coming to an open field, the rebels having taken up position on the opposite side behind embankments and breastworks, we made a stand” in “the open field,” Madox said. “Here the battle commenced in good earnest.”

Rather than fighting from cover, the heavy artillery regiments stood up, presenting juicy targets to their enemies. Formed on the division’s right flank, the Mainers fought around 2½ hours. Chaplin lost 77 men killed and 400 wounded.

Afterwards the 1st MHA contacted enemy troops almost daily and bled accordingly as Grant worked his way south and southeast and across the James River. “The regiment was under fire for 22 days” through June 18, the day that Chaplin saw his men murdered.2

By Petersburg the 1st MHA belonged to the 3rd Brigade (Brig. Gen. Gershom Mott), 3rd Division (Maj. Gen. David B. Birney), II Corps (Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock). Chaplin’s “regiment had dwindled” to around 900 men, Joel Brown recalled.

Plagued by his Gettysburg wound, Hancock relinquished II Corps to Birney Friday evening, June 17. Mott took over the 3rd Division and Chaplin its 3rd Brigade. With Lt. Col. Thomas H. Talbot sick, the 1st MHA’s command passed to Maj. Russell B. Shepherd.

Birney “pushed forward a strong skirmish line” either side “of the Prince George Courthouse Road” soon after dawn on June 18, Horace Shaw said. The skirmishers discovered enemy defenses abandoned near the Hare House and “a new line, the best that engineering skill could devise, bristling with rifles” and “artillery,” constructed nearer Petersburg.

With Maj. Gen. George G. Meade pressuring his corps commanders to attack the city, Birney sent his 2nd Division (Brig. Gen. John Gibbon) in at noon, only to be repulsed. Approximately three hours later, Birney ordered another attack involving the 3rd Division, supported on its left by the 1st Division (Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow) and a 2nd Division brigade.

About 3 p.m. the 1st MHA “came out of our breastworks” and shifted “up to the right, down a sunken road” (the Prince George Courthouse Road), Brown said. “Knapsacks, haversacks and blankets were thrown off” to “lighten our load,” and men wrote messages “to be sent home, in case anything happened.”

Chaplin watched from the Hare House through a telescope. “As we scrambled up out of the road, what a sight was before us,” Brown said. Some 1,000 to 1,500 “yards away, across an open field … covered with old corn stubble, were the rebel works, bristling with artillery, still as death.”

The distance was “some 400 yards,” estimated Capt. Frederic E. Shaw, Co. D.

A Chaplin aide that day, Horace Shaw also watched from the Hare House. “The whole division was to advance at the same time,” forcing the Johnnies to spread out their shooting, he said. Veteran regiments adjacent to the 1st MHA opted not to attack, the regiment went in solo, and “the enemy’s firing along their whole line was now centered on this field. The earth was literally torn up with iron and lead. The field became a burning, seething, crashing, hissing hell.”

“Ordered not to fire till they got into the enemy’s works,” the Mainers “went in cheering, marching in three Battalions 20 paces apart,” Frederic Shaw reported. “Before getting two thirds of the distance, nearly every man went down.”

Surviving the charge with only a shoe heel and a lock of hair shot off, Brown dropped into the sunken road and walked “towards the left to where the colonel [Chaplin] was” after leaving the Hare House. Up rode Mott.

“Col. Chaplin, where are your men?” he asked.

“There they are, out on that field where your tried veterans dared not go,” Chaplin replied. “Here, you take my sword,” he said, holding the blade out to Mott. “I have no use for it now.”

Then “the old hero sat down in the road and cried like a child,” Brown watched Chaplin’s reaction.

According to Horace Shaw, casualties incurred “in ten minutes” on that metal-swept cornfield amounted to 632: “115 killed, 489 wounded, and 28 missing.”

The attack shattered Daniel Chaplin, “struck him a mortal blow, from which he did not recover,” Horace Shaw observed. “When he saw them [his men] sacrificed … by a fantasy as deadly as useless, a melancholy discouragement took hold on him. He was surrounded by phantoms.”3

Wednesday, August 17 found the 1st Maine on the front line at Deep Bottom and Chaplin commanding the line that day.4 About 10 a.m. he stood “on the picket line, examining the enemy’s works with his glass,” reported Frederic Shaw. Chaplin knew he could not present a better target. He knew he should be reconnoitering from cover.

He “was seen, probably, by a sharpshooter,” likely two snipers. A bullet “wizzed by” Chaplin, who told Shaw, “Ah, they see me.”

“At that instant he was struck [by a second bullet] and fell, saying, ‘They have hit me this time,’” said Shaw. The colonel “was faint and bled freely.”

Stretcher bearers carried him to a hospital. The 1st Maine boys hoped Chaplin would survive. “We all feel badly — the whole regiment is attached to him,” Shaw commented. “We think the Colonel’s wound is too high up to be fatal. He appeared strong for one wounded so severely.”

Evacuated to a Philadelphia hospital, Chaplin died there on Saturday, August 20. Notified by telegram that day about his wounding, his family received on Sunday “a second despatch … that he died of his wounds.”

The bullet wound was listed as Chaplin’s official cause of death. Joel Brown disagreed. “Our colonel was broken hearted over his [regiment’s] loss and threw his life away at Deep Bottom soon after,” he explained.5

————

1 Joel F. Brown, The Charge of the Heavy Artillery, The Maine Bugle, January 1894, 8; 1860 U.S. Census for Bangor; Horace H. Shaw and Charles J. House, The First Maine Heavy Artillery, 1862-1865 (Maine, 1903), 141; Daniel Chaplin Soldier’s File, Maine State Archives

2 Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, 1864-1865, Appendix D (Augusta, Maine, 1866), 337-339; R. H. Stanley and George O. Hall, Eastern Maine and the Rebellion, (Bangor, Maine, 1887, 138-141; The Ellsworth American, Friday, June 3, 1864

3 Brown, The Charge of the Heavy Artillery, 4-8; Daily Whig & Courier, Wednesday, June 29, 1864; Shaw and House, The First Maine Heavy Artillery, 1862-1865, 121-129, 141

4 Horace Shaw and Lt. Col. Col. Thomas H. Talbot both wrote that Chaplin was shot on August 17. Frederic Shaw, who evidently was with the colonel, saw the hospitalized Chaplin shortly before 10 p.m., August 18, but not specifically cite that day as being when the colonel was wounded. Maine Adjutant Gen. John L. Hodsdon reported August 18 as the date of Chaplin’s wounding.

5 Brown, The Charge of the Heavy Artillery, 8; R. H. Stanley and George O. Hall, Eastern Maine and the Rebellion (Bangor, Maine, 1887), 146-147; Daily Whig & Courier, Monday, August 22, 1864

This was excellent. Thank you! I have always wondered about the circumstance surrounding Chaplin’s wounding at Second Deep Bottom.

Thank you, Todd.

The 1st Maine Heavies–great regiment. Their baptism of fire at Harris Farm on May 19, 1864, was a real slugfest, overshadowed by their later slaughter at Petersburg. No wonder Chaplin was so shaken up.

A sad story. Col Chaplin wanted to join his boys. Which is worse – a frontal assault or trench warfare ? Both horrific. The mentality then was different. Soldiers were expected to die. Aggressive officers expected no less. Poor Col Chaplin suffered from PTSD. Both sides slaughtered the other unmercifully. The objective was destruction of the opposing army which meant annihilation.

I had not considered that Chaplin suffered from PTSD. His death suggests he did not care any more, and his men noticed his attitude change after watching the 1st MHA slaughtered at Petersburg.

A terrible, poignant tragedy. His picture shows the eyes of a poet. This post puts a real human touch to the losses entailed in wartime. As Chris points out, Harris Farm was a hell of a baptism by fire, and the slaughtering fields of Petersburg no better. Too many lost their lives in too many ways owing to the hamfisted tactics often employed, and witnessing the losses carved out many hearts.

There are two versions of this particular Chaplin photo. Here he looks straight ahead; in the second photo *obviously taken at the same time) Chaplin turns his eyes slightly to the left to gaze directly into the camera. His is the countenance of a man who cared.

Thank you for an engaging and moving story.

For more insight on Chaplin’s state of mind after 6/18 you need to read General Robert McAllister’s letters. McAllister was a fellow Brigade commander in the same division as Chaplin. The mornin after the charge McAllister wrote of Chaplin I consider him a fair officer but I do think he might have made more of an effort to get off these wounded. General Regis de Trobriand in his memoirs after the war describe Chaplin as being marked for death and surrounded by phantoms. My read is that the experience of watching his regiment suffer in front of his eyes changed him but to say he intentionally exposed himself and thus wanted to die is to far of a stretch. He did have a family at home including young children. The fact is he continued to lead the regiment in additional actions for two months after June 18th.

Thanks for this very interesting article!

Patton was “old blood and guts.” “His guts, our blood,” said his soldiers, for example William Foley, author of “Visions from a Foxhole.” Chaplin, a man who had lived among his soldiers before the war, wasn’t of this ilk. No doubt, he thought of these men’s fathers, mothers, wives and their children, many he probably knew. If they had only been ordered not to shoot standing up at Harris Farm his men wouldn’t have been juicy targets.