Two earthen Civil War forts still stand in Maine

After Confederate Navy Lt. Charles W. Read captured the Revenue Service cutter in Portland Harbor in late June 1863, the Maine state government responded by constructing seven earthen batteries to protect five other seaports. The batteries shared a similar design and armament.

Because they were sited on federal property, two batteries still survive, well preserved in Maine state parks.

After attacking and capturing HMS Margaretta in Machias Bay in June 1775, colonists built earthen batteries along the lower Machias River to oppose Royal Navy incursions in far Down East Maine. Fort Foster has since vanished; a mile or so downriver the crescent-shaped Fort O’Brien mounted four cannons that could shoot across the river.

Although British forces later destroyed the fort, American troops rebuilt it, and a small garrison returned in 1808 amidst growing tensions with Great Britain. A Royal Navy squadron arrived in late summer 1814, and British troops burned O’Brien’s barracks and demolished the fort.

During the Revolution the British had defeated a Massachusetts expedition sent to capture Castine, a major Hancock County port on Upper Penobscot Bay. Colonists failed to take the multi-bastioned Fort George built atop Castine Neck, an arriving Royal Navy fleet annihilated the American fleet, and Britain only reluctantly returned eastern Maine after the war.

To protect Castine against unfriendly warships, the federal government constructed Fort Madison on the shore nearer the harbor entrance in 1811. Garrisoned by Army artillerists, the fort mounted four 24-pounder cannons.

The same British naval squadron that had captured Fort O’Brien then approached Castine on September 1, 1814. The American soldiers fired and spiked their guns before retreating. British troops occupied Castine and forts George and Madison (renamed Fort Castine) until mid-April 1815.

Technically still federal property, Madison emerged from almost 50 years’ obscurity after the Portland raid. Contractors built at each post an almost duplicate copy of the batteries constructed at Belfast and Rockland (two apiece) and Eastport.

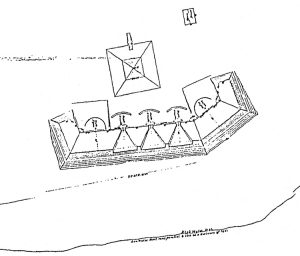

At Belfast, contractor Axel Hayford built each battery from “earth and stones pounded into a solid mass” and “covered with turf.” The sloping walls stood eight feet high, 18 feet wide at the top, 28 feet wide at ground level, and 150 feet long. “About forty feet” behind the walls at each battery Hayford built a pyramid-shaped powder magazine out of “logs, earth, and stone.”

The Fort O’Brien powder magazine was probably similar in dimensions to those built elsewhere. According to the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands, it measured 10-by-43 feet with a 12-by-18 “underground storage chamber for powder and ammunition,” over which “earth was piled . . . to protect it from mortar and shot.”

Each of the seven batteries mounted three 32-pounder smoothbores at the center embrasures and two 24-pounder rifled cannons mounted en barbette, one at either flank. Wooden barracks were built at each Belfast battery and likely at Fort O’Brien, where the state has identified a 10-by-14-foot storehouse site, and evidence suggests other buildings existed at the post, too.

Completed by late 1863 and garrisoned by companies of “Coast Guards Infantry” locally recruited and liable for call-up to federal duty, the batteries never fired their guns against hostile vessels. The Fort Madison garrison proved trigger happy, however.

In mid-November 1864, soldiers spotted “a supposed rebel pirate making for Castine” and “fired into” it and drove it away. The cheering barely died at Fort Madison when someone discovered “the ‘supposed privateer’ was the U. S. Revenue cutter Mahoning,” a Portland newspaper reported.

They must have a wonderful amount of stupidity in the Coast Guard at Castine, not to understand the signals of an American vessel, or to send their solid shot after such a vessel when she had dipped her colors, and observed all the rules for making herself known and understood by nautical men,” the newspaper chortled.

The incident, of course, caused a lot of eye-rolling around Penobscot Bay.

Abandoned after the war, most batteries disappeared beneath coastal development, but the federal government owned forts O’Brien and Madison into the 20th century (ditto granite-casemate forts like Knox and Popham). Washington transferred the forts to state control by the 1920s and ’30s.

Today the distinctive earthworks constructed in 1863 are preserved at Fort O’Brien State Historic Site and Fort Madison State Historic Site. The state keeps a cannon at each fort, mows its grounds and trims its grassy embrasured parapets, and maintains the on-site explanatory signage.

A granite monument identifies Fort O’Brien’s powder magazine, overtaken by shrubbery and trees; Madison’s pyramidal power magazine is kept neatly trimmed.

Access to both sites is free; be aware there are no toilet facilities at either site. To reach Fort O’Brien State Historic Site, turn onto Route 92 from Route 1 in Machias and drive south along the Machias River. The fort’s sign is located on the left, just before the Fort O’Brien School.

Fort Madison State Historic Site lies off Perkins Street in Castine, much nearer the Battle Avenue intersection than Main Street to the east. Watch carefully for the Fort Madison sign, almost lost against the background foliage. A narrow gravel driveway leads from Perkins Street to the site’s parking lot.

The Castine shore is readily accessible at Fort Madison.

Sources: Coast Batteries, Etc., Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine 1863 (Augusta, Maine, 1863), 43; Joseph Williamson, History of the City of Belfast in the State of Maine, From Its First Settlement in 1770 to 1875 (Portland, Maine, 1877), 486-490; That “Supposed Privateer at Castine, Portland Daily Press, Friday, November 18, 1864

I love Fort O’Brien. I’ve been there (after a slice of pie at Helen’s, of course), on my way to Jasper Beach, one of my absolute favorite places in the world. Here’s a peek (some non-Civil War writing from me): https://scholarsandrogues.com/2010/08/11/the-billion-billion-stones-of-jasper-beach/