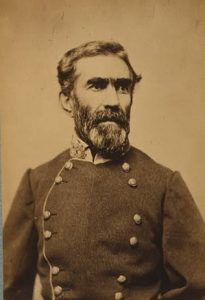

Symposium Spotlight: Braxton Bragg and Command of the Army of Tennessee

Welcome back to our yearly spotlight series, highlighting speakers and topics for our upcoming symposium. Over the coming weeks, we will continue to feature previews of our speaker’s presentations for the 2022 Emerging Civil War Symposium. We’ll also be sharing suggested titles that you may want to read in preparation for these programs. This week we feature Sean Chick.

No other single Confederate army commander has been as derided as Braxton Bragg. Neither of his successors had much success, but John Bell Hood took command in a desperate situation while Joseph E. Johnston never suffered a humiliating defeat. Both men had their charms. Johnston was popular with the troops and many of his subordinates. Not even Hood’s worst detractors would deny his bravery, nor his abilities as commander of an infantry brigade and division.

No other single Confederate army commander has been as derided as Braxton Bragg. Neither of his successors had much success, but John Bell Hood took command in a desperate situation while Joseph E. Johnston never suffered a humiliating defeat. Both men had their charms. Johnston was popular with the troops and many of his subordinates. Not even Hood’s worst detractors would deny his bravery, nor his abilities as commander of an infantry brigade and division.

Bragg had few of these traits. He lost great battles, his worst defeat being Chattanooga, where most of the Army of Tennessee was routed from the field. He was never loved by his men and he quarreled often with his subordinates. Making the contrast even more serve, before 1861 he was one of the regular army’s leading officers. He won fame at Buena Vista and his name featured in one of Zachary Taylor’s campaign slogans

Soon after the war it was argued that Bragg was one of the major authors of Confederate defeat. The argument was that Bragg should have been replaced with another commander, at least after Stones River. While Bragg certainly had his defeats, it was not a simple matter of removal. Jefferson Davis had a limited talent pool and Federal resources meant the Confederates needed not merely a good general, but a great one. In Virginia Davis had Robert E. Lee and in Louisiana Richard Taylor worked wonders with a pittance of men, but commanders of their caliber were rare. Davis tried to remove Bragg in early 1863, but Johnston refused to command.

Perhaps it is not so much that Davis should have removed Bragg, but rather who were the realistic candidates. The fact that there were so few explains one overlooked element of Confederate defeat. The South simply lacked enough first rate generals capable of field command. The North could of course stomach defeat better and their resources meant even a military incompetent like Nathaniel Banks could still take Port Hudson, even after suffering heavy losses. In addition, the North found a successful cast of commanders early in the war, including Ulysses S. Grant, George Thomas, and William S. Rosecrans. Bragg, seen as the army’s savoir in after Corinth fell, would face all three of those men and be defeated by all three of them.

Find more information on our 2022 Symposium and purchase tickets by clicking here.

After reading Earl Hess’s book about Bragg I’m convinced Leonidas Polk bears most of the responsibility for the discord in the AOT’s command structure. Not that Bragg is blameless. But in the early days of the war, in Pensacola his efforts met with general approval.

While Polk was absolutely a schemer and a cancer in that army, Bragg could not get along with anyone. Anyone at all. I can’t put “ most of the blame” on anyone but him.

General Bragg and the Peter Principle.

Braxton Bragg assumed command at Pensacola (his HQ was at the Rebel-occupied Navy Yard) in March 1861, replacing the ineffectual William H. Chase. Supposedly tasked with “taking possession of Fort Pickens, soon as possible,” the Pickens Truce between President Buchanan and ex-Senator Stephen Mallory remained in effect. And while Brigadier General Bragg found himself in a limbo situation not of his making, with thousands of untested Rebel volunteers arriving each month, West Point-trained Bragg made use of the empty hours to train and discipline those men. Even after Fort Sumter fell, the stalemate at Pensacola endured; and the training continued. By July/ August 1861 Braxton Bragg considered “his” army of perhaps 12,000 soldiers, well-trained. And he formulated a plan, and submitted a proposal: he would remain at Pensacola-Mobile and train new recruits, on condition he be allowed to swap trained soldiers for new arrivals, one-for-one. [This would have maintained his force level at about 12,000 while providing trained soldiers to the Confederacy, for use wherever needed.] Unfortunately for Bragg, his Training Camp proposal was overtaken by events: first he was offered command of the Trans-Mississippi, which he declined; then Confederate control of Kentucky began to unravel, and Bragg “and such force as he could provide” were ordered north. By February 1862 Braxton Bragg had amassed an army of trained, well-disciplined soldiers, numbering approximately 18,000. Of these, he left 6-8000 behind at Mobile and joined Albert Sidney Johnston at Corinth. And in April, the Battle for Pensacola was fought at Shiloh: in May 1862, Rebel-occupied Pensacola was abandoned, and all “facilities of potential use to the Federals” put to the torch.

The Pensacola Training Camp idea had merit, if for no other reason it would have kept Braxton Bragg away from control of the Army of Tennessee.