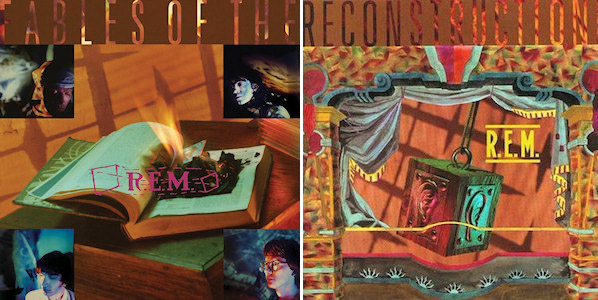

Fables of the Reconstruction

They had given their first two albums single-word titles—Murmur and Reckoning—but when it came time for R.E.M. to name their third album, they didn’t think another single-word title would do.[1] Lead singer Michael Stipe spoke to his father, a carpenter, who suggested “Reconstruction.”

It’s a word loaded with meaning, particularly for people in the South, where the Athens, Georgia, band was based. “Reconstruction” is a word that comes with a capital “R” and dark, complicated memories. Like “murmur” and “reckoning,” “reconstruction” was, says rock historian Grace Elizabeth Hale, “Another word with multiple meanings and southern roots that could, depending on a listener’s inclinations, suggest rebuilding and repair, an era of white southern humiliation, or the first flowering of African American citizenship.”[2]

According to band biographer David Buckley, though, Stipe later claimed “the album has less to do with Southern politics than more to do with the act of reassembly.”[3]

In fact, in that specific moment of the band’s history, “reconstruction” might have represented the very careful work the four musicians faced for themselves. As the story goes, as R.E.M. finished making an album that had proven artistically and personally challenging, they were as close to breaking up as they ever got in those early years. They needed to do some rebuilding.

The result was 1985’s Fables of the Reconstruction—although the album carried the alternative name Reconstruction of the Fables. If you held the cassette or CD with one side up, you had Reconstruction; if you flipped it around, you had Fables. “Unable to choose between Fables of the Reconstruction and Reconstruction of the Fables, they used both,” says Hale, who was part of the Athens music scene at the time.[4] The record company, IRS, officially went with Fables.

“The dialectical title itself is a clever word-play,” says Buckley: “here is an album that announces itself as documenting the fables from the Reconstruction era, but also seeks to reconstruct these fables for a modern audience. Past and present, fact and fiction, are intertwined. . . . In a sense, there is no history, only a ‘depthless present.’”

But rock historian Robert Dean Lurie sees the title more restrictively. “[T]he use of the term ‘Reconstruction’ is, on one level, a bit of a red herring,” he says. “There are no specific references on the album to the historical period that bears that name. . . .”[5]

Lurie offers a great description of that historical period:

a roughly ten-year span after the American Civil War during which the US government attempted to reintegrate the defeated South into the union by enfranchising freed slaves and promoting them to public office while barring former Confederate officials from holding government positions. All this while a flood of missionaries, teacher, and businessmen poured into the region with the interion of remaking both the Southern economy and the moral fabric of its society. Despite these generally noble aims . . . this scheme played out like most US military occupations usually do. That is to say, after much effort, expenditure of treasure, and a brief, tantalizing glimpse of the desired utopia at gunpoint, the whole thing collapsed into violence, corruption, chaos, and intimidation. A virulent new terrorist organization called the Ku Klux Klan emerged, the northern carpetbaggers were routed, and the South reverted to a racial caste system with wealthy whites on top, poor whites several rungs lower, and the black population at the very bottom.[6]

“The history would seem ripe for lyrical exploration,” says Lurie, “and yet, if there are any actual references to the Reconstruction era on Fables of the Reconstruction, they are deeply buried.”[7]

Not being native southerners, had R.E.M. unknowingly stumbled onto a fraught term? Drummer Bill Berry was from the upper midwest; Peter Buck was originally from California; and Michael Stipe, born in Georgia but raised in an ever-hopscotching military family. Only bassist Mike Mills had been raised in the Peach State (Buck did graduate from high school there).

“Stipe took a genuine interest in the American South,” claims Buckley, “approaching the subject not as a Southerner per se, but more as a tourist, historian or archeologist. What comes across is the feeling that this wasn’t the culture he lived in, but a foreign culture he wished to explore. His approach was thoughtful.”

Thoughtful, yes. But the album is often obscure, too—doubly so because of obtuse lyrics and Stipe’s tendency to mumble and murmur in a musical mix that treats the vocals as just one more of the instruments. That might all sound like a negative, but as a fan of the band since its early days, I can attest that those are all features that served as part of R.E.M.’s mystique and appeal.

The Old South is all over Fables of the Reconstruction, filled with quirky, gothic characters enmeshed in their own intractable pasts. “Much has been made of the Southern thread on Fables,” admits Lurie. “The South is certainly a key ingredient. . . .”[8] If William Faulkner’s southern Gothic characters had inhabited Sherwood Anderson’s grotesque Winesburg, Ohio, and it all got set to music, it would sound like Fables. “Time and distance are out of place here,” Stipe sings on “Feeling Gravity’s Pull.” That’s the world of the entire album.

There’s Wendell Gee, “reared to give respect” with good Southern manners. There’s Old Man Kensey, who “wants to be a sign painter./ First he’s got to learn to read./He’s gonna be a clown on TV.” If Reconstruction is a theme in Fables of the Reconstruction, it appears in oblique ways like that: something that, perhaps, maybe, might be a passing allusion to blackface minstrel shows. Or sunset laws, when “Green Grow the Rushes” warns, “Stay off that highway/word is it’s not so safe.” Or general deference to social superiors, when “Good Advices” advises, “When you greet a stranger/Look at his shoes” or “Look at her hands.” Wherever you look, don’t make eye contact.

In fact, “Good Advices” asks the million-dollar question about Reconstruction: “What do you have to change?”

The answer, of course, was “plenty.” For millions of Americans at the time, black and white, could the stakes have been any bigger?

My own favorite song from the album, “Driver 8,” offers an answer: “We can reach our destination, but we’re still a ways away.”

We could spend all day cherrypicking lines from Stipe’s lyrics to piece together an argument that Fables is about Reconstruction. What we do know, as Buckley reminds us, is that “the album’s title was settled on after the album had been completed. . . .”[9] So, any attempt to draw out a theme for the album is to impose one.

“And what are these songs if not reconstructed fables. . . ?” Lurie asks. Buckley agrees: “This was essentially a set of fables with the lyrics as music rather than words.”

Reconstruction might be woven in there, too, but to find it, we would have to do some reconstruction of our own.

————

[1] Grace Elizabeth Hale, Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture (Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 2020), 195.

[2] Hale, 195.

[3] David Buckley, R.E.M.: Fiction: An Alternate Biography (Virginia, 2002), 123.

[4] Hale, 195.

[5] Robert Dean Lurie, Begin the Begin: R.E.M’s Early Years (Portland, OR: Verse Chorus Press, 2019), 202.

[6] Lurie, 202.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, 201.

[9] Buckley, 123.

One 60’s song I do associate with the Civil War is Creedence Clearwater’s “Proud Mary,” a very different style of music. You can understand the words. Although the do not really relate to the war, “Rolling on the River” sure sticks in the mind as I study the Mississippi River campaigns. So does “Born on the Bayou.”

Also “Bad Moon Rising.”

“The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” by Joan Baez!

“Green Grow the Rushes” – one of my favorites off that incredible album. Kudos to you Chris on a very interesting and entertaining article!