A Forgotten Fort: Fort Tejon in Lebec, CA

A calm, crisp mountain breeze blew down from the Tehachapi Mountains into La Cañada de las Uvas (Grapevine Canyon). Major Jonathan Letterman, stationed here since December 1859, removed his hat, and wiped his forehead with the back of his hand. It was mid-May in 1861, and he had just received orders to report to Washington for a new assignment. There was a war on, and he was needed where the actual fighting would be, not just here at sleepy little Fort Tejon, minding the indigenous Emigdiano people collected on the Sebastian Indian Reservation.[1]

All in all, Letterman had enjoyed his posting at Fort Tejon. The weather was splendid if a little snowy in the winter. Established in 1854 by Edward Beale, Superintendent of California Indian Affairs, Tejon was the headquarters of the 1st U. S. Dragoons. In 1858, the fort was used by the experimental U. S. Camel Corps. This novel approach to transportation used camels to carry supplies across the deserts of the American southwest. Unfortunately, the camels proved to be temperamental and spooked the horses used by the cavalry which accompanied them.[2]

Letterman did not mind the camels, but it took a while for an easterner like himself to get used to the earthquakes. In 1857 there had been “a big one.” Although it was centered ninety-three miles away, it was known as the Fort Tejon Earthquake because the most reliable reports of the event came from the men at the fort. Luckily, Major Letterman had missed that one.[3]

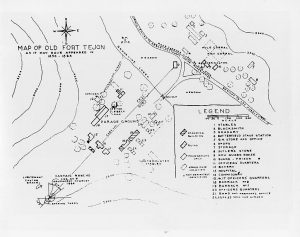

The men at Tejon were mounted dragoons, for the most part. In addition, there were cooks, blacksmiths, wives, and children. A quartermaster was located here, supplying the army and other government services. Local passengers waited at the Butterfield stagecoach station, which ran along the Stockton-Los Angeles Road, delivering mail on the overland route.[4]

And now Major Letterman would be leaving the small adobe fort behind. He thought about this place called “California.” It was one of thirty-four states, but English was certainly not the predominant language. Even the word “adobe” had been strange at first, but it was certainly better than saying “mud brick” to describe how the buildings at Tejon were constructed. Furthermore, spicy chunks of meat rolled up in a flat piece of cornbread, called a “tortilla,” and cooked in a pan over an open flame? Now there was a treat rarely seen in Philadelphia. Letterman would miss the sights, sounds, and smells of the place he had called home for a year. “What would happen to the fort now that there was going to be a war?’ he wondered. Well, it was not his problem. He needed to pack and get on one of those Butterfield stages. Washington was almost 3,000 miles away. Maybe he would be able to get back to this beautiful golden state sometime in the future. When one is in the army, however, the future takes care of itself. Major Letterman turned, replaced his hat, and entered the shade of the Officer’s Quarters. “Better get started,” he thought.

Letterman left Fort Tejon, followed by most of the U. S. Army soldiers. However, the fort remained occupied by California volunteer troops through 1863. Those units included Companies D, E, and G of the 2nd California Volunteer Cavalry from July 6 to August 17, 1863, and Company B of the 2nd California Volunteer Infantry, which remained there until Fort Tejon was abandoned for good on September 11, 1864. There it remained, in Grapevine Canyon, left to the elements.[5]

In 1940, a group of local citizens urged the Tejon Ranch Company, now the owners of the land under and around the fort, to deed five acres of land to the State of California. A state park was established at that time. The remaining original buildings–the Barracks and the Commanding Officer’s Quarters–were documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey and listed on the National Register of State Historic Places. Both buildings are open to visitors. The barracks contain displays of original uniforms and recreated troopers’ quarters. The commanding officer’s quarters have several restored and furnished rooms. Nearby parts of buildings are stabilized by lumber, masonry, and reinforcing rods. Restoration work, as well as archeology projects, are ongoing. There is a park office and restrooms, but they are open depending on current Covid restrictions. Natural features include centuries-old valley oaks and regular sightings of California condors.[6]

The Fort Tejon Historical Association, which has been around for a long time, remains active and involved. Men, women, and children show up on specific weekends to represent the dragoons and their families. A blacksmith often shares his craft, and something is always cooking. No camels have shown up, but one never knows! Additionally, Fort Tejon is one of southern California’s most active Civil War re-enactment sites. Like everything else, demonstrations and battles have been canceled because of Covid, but the doughty FTHA does everything possible to keep both the Dragoon and Civil War programs alive.[7]

If you have the chance to visit this beautiful little gem of history, conveniently located off I-5, please call ahead to see what is available. The worst that can happen is that you can stand on Major Letterman’s porch, take off your hat, wipe your forehead and spend a few minutes lost in thought. More of that, please!

[1] https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=585

[2] http://www.militarymuseum.org/Camel.html

[3] https://scedc.caltech.edu/earthquake/forttejon1857.html

[4] Fort Tejon State Historic Park pamphlet, State of California, Department of Parks & Recreation, Sacramento, California, 1991

[5] https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=585

[6] Ibid.

[7] http://www.forttejonca.org/

Several buildings, lots of exhibits, and only 40 yards off I-5 near the top of the Grapevine. A nice stop after driving several hours. Then back on the freeway in minutes.

They used to have monthly Civil War reenactments at Fort Tejon. I reeanacted there for many year when I lived in California.

We had a Confederate hospital.

.