The “Lost General” is at Last Found

ECW welcomes guest author Bruce Allardice

In May of 1861 a stocky, handsome man of military bearing walked into a recruiting office in Jackson, Tennessee, at the head of a group of volunteers from Memphis. He gave his name as R. C. Tyler, and his age as 28. He was a stranger to Memphis. But his name had been in the newspapers in recent years, first as an officer of William Walker’s Nicaragua army, and later as the promoter of another filibustering expedition.[1] The Confederacy lacked men of military experience, so a man of Tyler’s background and manifest abilities soon saw him promoted to brigade quartermaster and then to Lt. Colonel of the 15th Tennessee Infantry. He led the 15th at Shiloh and Perrysville, being wounded in the former battle and earning the full colonelcy. Praised by a fellow soldier as “one of the bravest men I ever saw,” General Braxton Bragg appointed Tyler provost marshal of the Army of Tennessee. He led the 15th at Chickamauga, where he was again wounded, and at Chattanooga, this time commanding a brigade. At this battle Tyler suffered a wound that caused amputation of his leg.

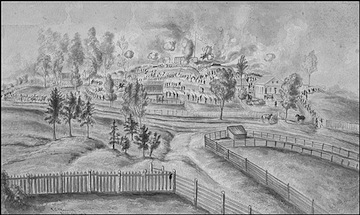

The crippled officer had earned promotion to Brigadier General, which came to him in March 1864 while he was still hospitalized. Unfit for further field duty, he instead was made commandant of the post of West Point, Georgia. It was at West Point on April 16, 1865, a week after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, with the Confederacy collapsing and James Wilson’s Union cavalry overrunning southwest Georgia, that Tyler mustered a handful of militia and convalescents to defend an earthwork defending the city, named Fort Tyler in his honor. For three hours 120 ragtag Confederate fought off 3,000 Union cavalry. But the fort eventually fell, along with the general it was named for. Early in the action a Union sharpshooter killed the general. Tyler became the last general killed in action during the Civil War.

Tyler’s war record is well known. But who was he?

Before now, what little was known came from reminiscences from old army comrades, who recalled that he had fought in William Walker’s filibusterer army in Nicaragua in 1857, that he lived in Baltimore prior to coming to Memphis, and that he was a stranger to Memphis when he enlisted in 1861. Tyler has been termed the “Mystery General…. The South’s Shadowiest Figure.” Historian Ezra Warner, in his seminal Generals in Gray, labeled Tyler “by all odds the most enigmatic figure of the 425 generals of the Confederacy,” a man of “mystery” who “stepped from absolute obscurity… and then dropped back to oblivion.” Subsequent historians such as Jack Davis and Stuart Sanders have been forced to admit that, other than his military career, “almost literally nothing is known about him.” [2]

My own 1995 article in Civil War Times Illustrated put more flesh on who Tyler was, particularly his background as a prominent filibusterer. He’d been a lieutenant in Walker’s army, and after Walker’s surrender he’d briefly lived in Baltimore—confirming the reminiscences. My article uncovered his prominent role in the Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC), George W. Bickley’s short-lived filibustering group that issued a nationwide call for money and volunteers. Tyler chaired the sparsely attended 1860 KGC “national convention” and criss-crossed the country trying to raise money for the cause. But still there was nothing definite on his family or his pre-1857 background.

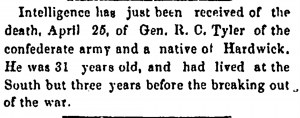

But I kept up my interest in Tyler. And the advent of online digitalized newspapers enabled new resources and searches to be made. Imagine then my surprise when four years ago I ran across this item in an 1865 Massachusetts newspaper:

Of course historians know that newspapers in the 1860s (and newspapers today) are not always accurate or reliable. This notice alone can’t be accepted as definitive proof of who General Tyler was. Still, this newspaper item provided a start to further research.

The simple part was to determine if there existed an “R. C. Tyler” of suitable age who ever lived in Hardwick, Massachusetts (a small town 20 miles west of Worcester). Hardwick baptismal records showed a “Reuben Cutler Tyler” as being the only “R. C. Tyler” baptized during that period. Reuben was born Dec. 4, 1832, the son of Reuben and Elizabeth (Billings) Tyler. The family appears on the 1850 census of Hardwick, the father being a farmer of modest means, with Reuben listed as age 17 and a laborer on the farm. The father’s 1859 will lists his son Reuben Cutler as a beneficiary, along with his daughters Sarah Clementine and Eliza Elizabeth.[3] A well-known genealogy of the Tyler family not only gives data on this family, but clearly states that Reuben Cutler died close to the same day as “General R. C. Tyler” did.[4]

My 1995 article on Tyler speculated that in the 1850s he lived in the then semi-frontier state of California, the state where William Walker recruited a large portion of his filibusterers. This speculation matches up with Reuben. By 1852 he’d moved to Yolo County, California, being listed as a “farmer,” born Massachusetts, on the 1852 California state census. By 1855 he’s being sued for debts in Sonoma County.[5]

Tyler’s connections with the “Knights of the Golden Circle,” a filibustering group, furnished the clue to the last link in his identification. The KGC was founded by a shady character, George W. Bickley, with “R. C. Tyler” as his chief deputy. From his comrade’s reminiscences, we knew the KGC’s “R. C. Tyler” was the general. What was left was to prove that Reuben was the KGC’s Tyler.

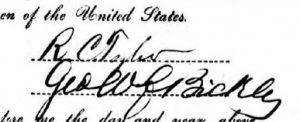

In recent years scans of US Passport applications have gone online. A search of them revealed that in January 1860 “Reuben C. Tyler” applied for a passport (presumably to travel abroad to explore more filibustering opportunities). His passport application is witnessed by none other than George Bickley, who also applied for a passport about this time.

In the passport application Reuben states he was born in Massachusetts, and lives in Maryland. The handwriting in the “R. C. Tyler” signature on this application compares favorably to General Tyler’s wartime “R. C. Tyler” signature.

So how did Reuben Cutler Tyler morph into “Robert Charles” Tyler? In his compiled service record, he uniformly signs documents, and is referred to as, “R. C. Tyler.” A search of online newspapers through the 1890s shows that the general was always referred to as “R. C. Tyler.” It isn’t until the early 1900s that the first names “Robert Charles” are added. The impetus for this comes from one of Tyler’s old army comrades, W. J. Slatter, who in 1896 wrote an article on the Battle of West Point published in The Confederate Veteran. For previous historians, the article was the main primary source on Tyler’s life, and in it Slatter calls him “Robert C.” Slatter references a letter of Tyler’s written early in 1865.[6] It is of course possible that Slatter mis-transcribed the letter, or that Tyler preferred to be known as Robert to conceal his northern background.

With these discoveries we now know the main reason why historians never found “Robert Charles” Tyler—because he never existed.

Bruce S. Allardice is a professor of history at South Suburban College, near Chicago. He has authored, or co-authored, 6 books, and numerous articles, on the Civil War, including “More Generals in Gray” and “Confederate Colonels.” He is past president of both the Chicago and Northern Illinois Civil War Round Tables.

[1] “Filibusterer” is defined as “An adventurer who engages in a private military action in a foreign country.” Filibustering expeditions like Walker’s were common in the 1850s.

[2] Ezra Warner, Generals in Gray (LSU Press, 1959); William C. Davis (ed.), The Confederate General (National Historical Society, 1991); Stuart Sanders, “Robert Charles Tyler,” Military History Quarterly, Spring 2006; Bruce Allardice, “Out of the Shadows,” Civil War Times Illustrated, Jan/Feb. 1995.

[3] Hardwick vital records, 1850 MA census, 1859 will, accessed via ancestry.com. At the time of his death Reuben owned a 128-acre farm, plus 66 acres of meadowland. See Barre Gazette, April 13, 1860.

[4] Willard Tyler Brigham, The Tyler Genealogy. Descendants of Job Tyler of Andover (1912) v. 2, p. 427. The April 25 date is taken from the newspaper. However, Tyler was killed on the 16th. The Worcester newspaper probably received a garbled report of Tyler’s death—a common occurrence at the time.

[5] 1852 California State Census, Yolo County, shows “R. C. Tyler,” age 20, born Massachusetts. Court documents (in the Petaluma Sonoma County Journal, April 25,1855) make it plain Tyler couldn’t be found, presumably because he had already joined William Walker’s filibusterers.

[6] W. J. Slatter, “Last Battle of the War,” Confederate Veteran, v. 4 (1896), p. 353.

In the absence of the Internet or other means of general communication prior to the Nineteenth Century, it was possible to reinvent yourself. Obviously this is what Reuben Cutler Tyler did. We are left to wonder why R. C. chose the South when he had been reared in Massachusetts. Without more facts, this is a splendid opportunity for fiction. Thanks to Professor Allardice for a fascinating article.

Cool article, great detective work on R. C. Tyler. Amazing how the Internet enabled further research on this mysterious soldier.

Thanks, Larry.

I’ve also just “discovered’ the unknown Confederate Congressman, M. H. MacWillie of the Arizona Territory. I’ll be editing his wikipedia bio and posting on the CECW thread for the Southwestern Symposium.

Excellent digging!

Great article Bruce!

Great, solid work. Thanks for sharing!

Prior to conducting research into “The Origin of the Disunion Movement,” this author had assumed that the organization known as Knights of the Golden Circle was little more than a bit player, or distraction in what became the main events of secession and Civil War. Founded in Cincinnati in 1854, it was written off as a “midwestern association of Southern sympathizers” and for the longest time the most senior members of the organization were identified as George W. L. Bickley and “Robert” C. Tyler… not names familiar to most Civil War enthusiasts. Recently, more serious study (by David Keehn) has brought to light the jaw-dropping identities of pre-Civil War leaders who were members of the KGC (many of whom had been suspected, but proof was lacking.)

Thanks to Professor Allardice for sharing this valuable research on just one of the shadowy frontmen promoting the secret society devoted to creating a Slavery-based empire.

Thanks to all for your kind words.

Nice work!

Tom