The First Draft of Naval History: USS Minnesota’s Deck Log and the Battle of Hampton Roads

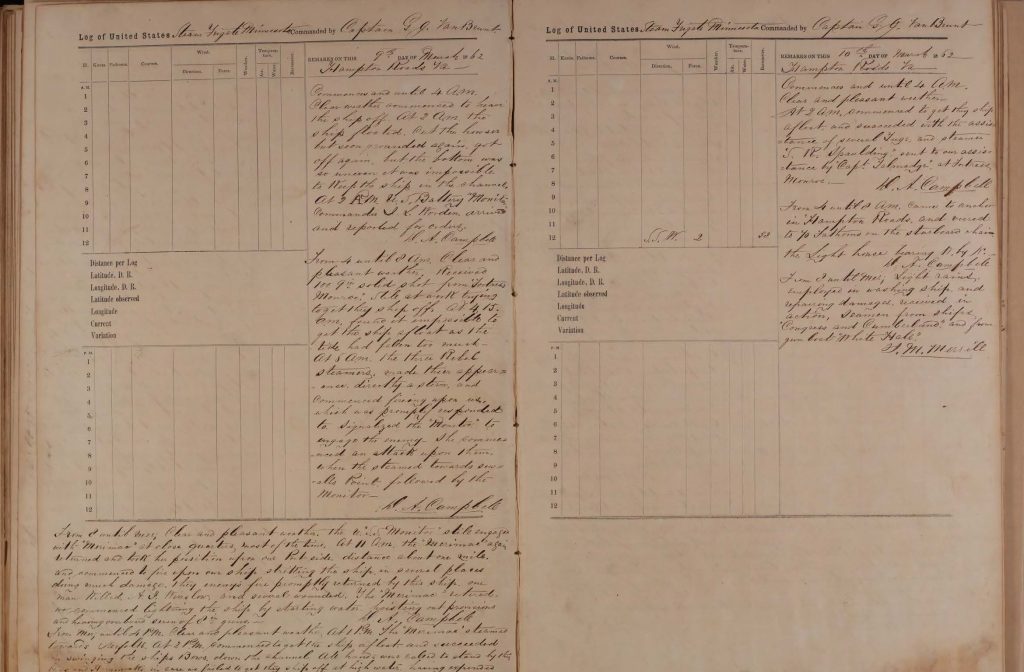

In naval circles, the deck log is sacred. It is a ship’s official record, documenting location, weather, personnel and supply transfers, and changes in course and speed. Anything significant, important, or novel is recorded in a ship’s log and signed off at the end of each watch by the officer of the deck, certifying its accuracy. These logs form the first draft of naval history.

Deck logs of Civil War warships now reside in the National Archives. For naval historians, these are must use sources, but for those who do not often delve into naval history, they often represent a missed opportunity. For example, anyone researching 1862’s Peninsula campaign can use U.S. Navy deck logs to learn changes in weather, what supply vessels supported George McClellan’s movements, and how warships supported the Army of the Potomac near Malvern Hill.

Recently, there have been significant advances in access to Civil War deck logs. In the last five years, thanks to grants for gathering data to track climate patterns, many Civil War era logs have been digitized on the National Archives website.[i] The project has completed its look at the Civil War era and the National Archives is now working on the Vietnam War era. Logs for fifty Civil War warships have been made available online.

The most famous Civil War naval engagement, the Battle of Hampton Roads, occurred 160 years ago on March 8-9, 1862. CSS Virginia, accompanied by several improvised and converted war steamers, struck the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron on March 8, sinking USS Cumberland, burning USS Congress, and forcing USS Minnesota aground. March 9 saw the timely arrival of USS Monitor, which successfully defended the grounded Minnesota, fighting the first battle between ironclad warships in the process.

Logs of two warships present at Hampton Roads are digitized, that of Monitor and Minnesota. Since the turreted ironclad Monitor rightfully gets the most attention in this battle, I wanted to look at the battle through a different lens, that of Minnesota, by diving into its log from the two days of combat. The pages reveal interesting anecdotes about Minnesota’s participation in the battle, including how its crew undertook superhuman efforts to refloat their ship, and how the sailors present in Hampton Roads first documented the Civil War’s most famous naval battle.

The morning of March 8, 1862, began as many others for Minnesota’s crew, with beautiful weather allowing for an easy transfer of mail from an approaching boat. The easy morning shifted to a chaotic afternoon when Minnesota’s deck officer observed “three steamers off Sewall’s [sic.] Point” closing the blockade; Captain Gershom J. Van Brunt ordered the steam frigate to slip its anchor, releasing it to allow the ship to maneuver, before closing the approaching Confederates.[ii] Shore batteries at Sewell’s Point starting a heated artillery exchange with Minnesota at 2 P.M. One Confederate shell damaged Minnesota’s main mast, and after an hour of firing, the frigate ran aground a mile from Newport News.

“We backed the Engine and set the mizzen topsail to back the ship off, but all to no effect.”[iii] The frigate was firmly aground, at the mercy of CSS Virginia, which was then attacking USS Cumberland and USS Congress. There, the ironclad made history, which Minnesota bore witness to: “At 3.30 P.M. the ‘Cumberland’ went down with her Colors Flying. At 4 P.M. the ‘Congress’ struck her Colors and hoisted a white flag.”[iv] Miles away, entering Hampton Roads’ outer approaches, USS Monitor’s officer of the deck recorded “heavy firing in distance.”[v]

After sinking Cumberland and forcing the surrender of Congress, CSS Virginia closed Minnesota. Captain Van Brunt’s sailors “immediately transported four of the broadside guns to the bow ports, and commenced firing” at the Confederate ironclad and its two wooden escorts, Jamestown and Patrick Henry, but with little effect.[vi] With light fading, the Confederates withdrew, set to return the next day to finish Minnesota off.

Recognizing this, Captain Van Brunt’s crew worked through the night to refloat the frigate. Doing so was a delicate process. Refloating a grounded ship was easiest done at high tide, when ocean water flooded into Hampton Roads, raising water levels. The Hampton Roads area experiences diurnal tides, meaning that high tide comes twice daily. Based on Minnesota’s log, it appears that high tides for the Sewell’s Point area were at approximately 2 A.M. and 2 P.M. during the battle. Twice the ship was temporarily freed before being stuck in the mud again. During the attempts, at 2 A.M, USS Monitor arrived with orders to “render assistance to US Steam Frigate ‘Minnesota,’” so delighting Captain Van Brunt that he claimed all on his frigate “felt that we had a friend that would stand by us in our hour of trial.”[vii]

At dawn on March 9, the Confederate squadron renewed its efforts to sink USS Minnesota and break the Hampton Roads blockade. Minnesota’s crew witnessed the first battle between ironclad warships, as USS Monitor “commenced an attack,” engaging CSS Virginia “at close quarters most of the time.”[viii] When the ironclads were close enough, Minnesota added its own artillery to the fight as well.

By midday, CSS Virginia began withdrawing from the scene of action. Despite this, Captain Van Brunt did not know whether the Confederate ironclad would return the next day after resupplying. So, while USS Monitor received laurels and visits from dignitaries (including Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox), Minnesota fought to refloat itself once again.

The vessel’s log highlights the tedious work filled with setbacks: “We commenced lightening the ship by starting water, hoisting out provisions and heaving overboard seven of 8in guns.”[ix] This might lighten the ship to allow it to refloat at the next high tide. After several hours, the crew “succeeded in getting the ship afloat,” but “again grounded” after steaming only a few hundred yards.[x] There it remained, awaiting the next high tide. In the pre-dawn hours of March 10, Minnesota succeeded in getting refloated, “with the assistance of several tugs and steamer ‘S.R. Spaulding.’”[xi]

Around dawn, the frigate anchored in deeper water and started “repairing damages received in action,” anticipating a renewed battle that would not occur.[xii] Unknown to Minnesota’s sailors, CSS Virginia was preparing to enter dry-dock for repairs. The first ironclad battle was over, the blockade of Hampton Roads was momentarily secured, and USS Monitor proved itself in combat, successfully protecting the grounded Minnesota. Nothing represents that victory more than the words of Monitor’s captain, Lieutenant John L. Worden. Blinded when one of CSS Virginia’s shells struck his ship’s pilothouse during the height of the battle, Worden was taken below for medical treatment. As combat concluded, his officers checked on him. When Worden learned that his turreted ironclad saved USS Minnesota from destruction, he curtly claimed “Then I can die happy.”[xiii]

Aground and unable to fully participate in the fighting on either March 8 or 9, USS Minnesota witnessed the Confederate ironclad Virginia’s strikes against the blockade’s wooden vessels, as well as the defense of that squadron by USS Monitor. Something must be said however, that Minnesota’s crew did not sit idle waiting for CSS Virginia to shell them into submission. Instead, Minnesota’s log documents the loss of USS Congress and USS Cumberland, the battle between Monitor and Virginia, attempts by USS Minnesota to participate in the fighting, and the herculean efforts of Captain Van Brunt’s crew to refloat their frigate, often while under enemy fire, so they might better help their fellow shipmates.

By no means is USS Minnesota’s deck log the premier source for the Battle of Hampton Roads. But the availability of these logs, the first draft of the battle’s history, allows us to see what mattered to the ships, their officers, and crews in those pivotal days.

Sources:

[i] Hannah Hickey, “Civil War-era U.S. Navy ship’s logs to be explored for climate data, maritime history”, January 18, 2018, UW News, https://www.washington.edu/news/2018/01/18/civil-war-era-u-s-navy-ships-logs-to-be-explored-for-climate-data-maritime-history/, accessed January 12, 2021; To help researchers, Civil War Navy – The Magazine has posted a document on their website compiling links to all of these logs, sorted by ship and date.

[ii] March 8, 1862, USS Minnesota Logbook, Logbooks of US Naval Ships, 1801-1940, Record Group 24: Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798 – 2007. US National Archives.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] March 8, 1862, USS Monitor Logbook; Van Brunt to Welles, March 10, 1862, “Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Commanding Officers of Squadrons, 1841-1886”, North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, M89, RG 45, US National Archives.

[viii] March 9, 1862, USS Minnesota Logbook.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] March 10, 1862, Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] S. Dana Greene, “In the ‘Monitor’ Turret,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, (New York, The Century Co., 1887), Vol. 1, 727.

thanks Neil, great story … i knew MINNESOTA ran aground and was saved by MONITOR, but did not know all details of the ship’s efforts to get off the mud … i.e., heaving 8″ guns over the side … there is great stuff in those old deck logs … and much more detail then recorded in my Navy days … thks for lettiing us know about this great resource … well done and thanks agian.

Thanks so much Mark. While most people studying the war might find these logs filled with too much of the mundane activity of ship life and daily routine, that is exactly what many examining the naval side of things love to see. Also, they are filled with gems of information that might not be recorded elsewhere.