Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet in Chattanooga, Part II

ECW welcomes back guest author Ed Lowe

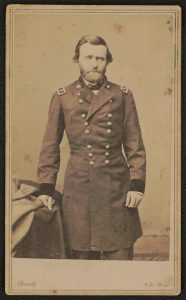

James Longstreet and Ulysses S. Grant had known each other from their West Point days and into their initial assignments at Jefferson Barracks close to St. Louis. Longstreet was well aware of the man President Abraham Lincoln had now chosen to head up operations in Chattanooga, Tennessee in the fall of 1863. One of the first steps Grant took upon receiving command of the new Military Division of the Mississippi was to replace the Army of the Cumberland’s commander, Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, with the Virginian-born Maj. Gen George Thomas. Arriving on the 23rd of October, Grant immediately set out to reverse the debilitating supply situation and for that, he turned his attention to an also-recently-arrived officer to Chattanooga, Brig. Gen. William Smith, new chief engineer for the Army of the Cumberland.

James Longstreet and Ulysses S. Grant had known each other from their West Point days and into their initial assignments at Jefferson Barracks close to St. Louis. Longstreet was well aware of the man President Abraham Lincoln had now chosen to head up operations in Chattanooga, Tennessee in the fall of 1863. One of the first steps Grant took upon receiving command of the new Military Division of the Mississippi was to replace the Army of the Cumberland’s commander, Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, with the Virginian-born Maj. Gen George Thomas. Arriving on the 23rd of October, Grant immediately set out to reverse the debilitating supply situation and for that, he turned his attention to an also-recently-arrived officer to Chattanooga, Brig. Gen. William Smith, new chief engineer for the Army of the Cumberland.

General Smith birthed a plan to relieve the army’s challenging supply issues by capturing Brown’s Ferry, constructing a pontoon bridge over the Tennessee River, securing Lookout Valley, and establishing reliable contact with the supply depot at Bridgeport. Grant approved the plan, which Smith put into motion for an early-morning operation on October 27. The plan called for launching 50 pontoon and flatboats carrying over 1,600 troops under the command of Brig. Gen. William Hazen at midnight on the 26th of October, making the nine-mile voyage along the Tennessee River, around Moccasin Bend, and landing at Brown’s Ferry for the assault against a meager Confederate force. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. John Turchin’s brigade of nearly 4,000 troops would cross Moccasin Bend. Once Hazen secured the landing area, the pontoon boats would shuttle Turchin’s men over. The result would be a pontoon bridge across the river and into the city. Also strengthening U.S. forces in the area, newly arrived Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker would advance from Bridgeport with the 11th and 12th Corps and link up with forces from the ferry. It was a robust and intricate plan requiring precision but Grant’s propensity for offensive action fit perfectly with the proposal. Little did Longstreet or his men know what was to fall upon them.

Hindering efforts along Longstreet’s front were two U.S. artillery batteries expertly anchored on Moccasin Bend, a piece of land opposite the northern end of Lookout Mountain across the Tennessee River. The cannoneers had zeroed their guns to almost every visible route along the face, making it near impossible to quickly move men and supplies from one side of the mountain to the other. Counter-fire by Longstreet’s artillerist, Colonel Edward P. Alexander, or into targets inside Chattanooga proved ineffective. As historian Alexander Mendoza pointed out, the battery’s presence made “a Confederate advance against the supply line impossible.”

Colonel William Oates and his 15th Alabama Infantry held the precarious position at Brown’s Ferry, along with elements of the 4th Alabama. On the night of October 26, Oates had gotten wind that there was U.S. activity around Bridgeport; however, his plea for confirmation and reinforcements went unanswered. So, Oates, in the waning hours of that day, went to sleep. Meanwhile, Hazen’s men floated quietly down the river, reaching their objective around 4:30 in the morning of October 27. Men of the 23rd Kentucky Infantry landed on the west bank and moved against surprised Confederates. One Alabama soldier expressed in his diary that the U.S. soldiers “had us in a trap and could have captured us with ease had they pushed on.” Mission accomplished; the U.S. soldiers began building a pontoon bridge across the river. Smith’s operation had exceeded expectations and the aggressiveness of Grant paid off. Carrying a wounded Oates with them, the Confederates swiftly withdrew toward Lookout Creek.

Blame and heightened emotions soon followed; Bragg was furious and demanded not only answers but also action to reverse the situation at Brown’s Ferry. Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws and Brig. Gen. Evander Law placed responsibility on Longstreet for the loss that he did not cast enough attention to this area. His biographer, Jeffry Wert, concluded that Longstreet “seems not to have demonstrated serious interest in the region until it was too late.” The following morning, October 28, Longstreet and Bragg met on Lookout Mountain for the first time since Davis left Chattanooga two weeks earlier.

As the two conversed, an excited Confederate soldier rushed up, proclaiming that U.S. troops were moving through the valley below. Bragg believed this was nonsense. “General, if you ride to a point on the west of the mountain I will show them to you,” the young soldier replied. Both generals were stunned at what they saw, two U.S. corps marching along the valley toward Brown’s Ferry. Just a day removed from having lost the key terrain of Brown’s Ferry, Bragg wanted the ferry brought back under Confederate control, and immediately. Longstreet, however, noticed something else. A force of about 1,500 soldiers had halted about three miles in the rear of the main body, around the area of Wauhatchie. This force was a small division of the 12th Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. John Geary. “A plan was laid,” Longstreet pointed out in his memoirs, “to capture the rear-guard by night attack.” Longstreet launched into action the battle of Wauhatchie.

Braxton Bragg offered up to four divisions to retake the Ferry. As historian David Powell indicated: “For good reasons, Longstreet believed this to be impractical.” He would have to wait until night to move forces around Lookout Mountain; the pesky U.S. batteries on Moccasin Bend made this impossible. Longstreet recognized moving reinforcements across the face of the mountain would take time, given the batteries below. Perhaps more importantly, the U.S. forces would have ample notice to respond to large Confederate movements. Still filled with doubt, Longstreet waited on Lookout Mountain until around midnight on October 28th. As he and his officers assembled, discussing the operation, Longstreet realized that McLaws had not been given orders. With only the division of Jenkins on hand, his chance of success slashed in half, Longstreet called the operation off, or so he thought. “Under the impression that the other division commander understood that the move had miscarried,” Longstreet confessed in his memoirs, “I rode back to my headquarters, failing to give countermanding orders.” Brig. Gen Micah Jenkins, however, went full steam ahead. Or, as Longstreet stated, “the gallant Jenkins…decided that the plan should not be abandoned.” Longstreet failed to give clear instructions to Jenkins, or at least enough to convey the operation was off.

Brigadier Generals Evander Law and Jerome Robertson moved their two brigades to block the road leading to Brown’s Ferry, with Jenkins placing Law in charge of this sector. Brig. Gen. Henry Benning’s brigade covered the line of retreat back across Lookout Creek, leaving only Colonel John Bratton’s South Carolina brigade to mix it up with Geary’s defending force at Wauhatchie. With orders relayed, the veterans of many hard-fought battles moved out for a rare night action.

Longstreet rested in his headquarters while one of his divisions went into action. Geary’s men held up to Bratton’s attack. Bratton had no alternative but to pull back across Lookout Creek. Blame floated around Longstreet’s command as to who pulled out first and when with Law catching much of the criticism. The loss of Brown’s Ferry and the night action at Wauhatchie sealed the fate of General Lee’s veteran First Corps. Wauhatchie and the deteriorating relationship between Longstreet and Bragg facilitated Bragg’s decision to send Longstreet into East Tennessee toward Knoxville. With Grant gaining strength every day, this was just the opening Grant needed to finalize his offensive plans and secure Chattanooga. The question for the Confederates was: Could Longstreet complete his mission against U.S. forces in and around the Knoxville area and return to Chattanooga before Grant opened his assault? Part III of this series will focus on the question of whether Longstreet had won at the battle of Campbell’s Station and returned to Chattanooga before Grant attacked.

COL (ret) Ed Lowe served 26 years on active duty in the U.S. Army with deployments to Operation Desert Shield/Storm, Haiti, Afghanistan (2002 & 2011), and Iraq (2008). He attended North Georgia College and has graduate degrees from California State University, U.S. Army War College, U.S. Command & General Staff College, and Webster’s University. He is currently an adjunct professor for the University of Maryland/Global Campus & Elizabethtown College, where he teaches history and government. He is currently working on two books for Savas Beatie. The first covers Longstreet’s First Corps from Gettysburg to East Tennessee, and the second is an Emerging Civil War Series book on Longstreet’s East Tennessee Campaign. He is married with two daughters and lives in Ooltewah, Tennessee. He currently serves as President of the Chickamauga & Chattanooga Civil War Round Table, reconstituted in September of 2020.

Suggested Readings

Longstreet, J. (1984). From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. Blue and Grey Press.

Mendoza, A., & And, F. (2008). Confederate struggle for command: General James Longstreet and the First Corps in the West. Texas A & M University Press.

Powell, D. A. (2020). The impulse of victory: Ulysses S. Grant at Chattanooga. Carbondale Southern Illinois University Press.

?Sword, W. (1995). Mountains touched with fire: Chattanooga besieged, 1863. St. Martin’s Press.

?Wert, J. D. (1994). General James Longstreet: the Confederacy’s most controversial soldier: a biography. Simon & Schuster.

?Woodworth, S. E. (1998). Six armies in Tennessee: the Chickamauga and Chattanooga campaigns. University Of Nebraska Press.

While it is well known the Booth family provided America great Shaxperean actors, in 1846 when the Fourth Infantry was stationed in Corpus Christie prior to the war, James Longstreet, nominated for but disqualified by his height from the role of Desdemona in “Othello,” entertainment intended to relieve the tedium of the assignment, and a play which contains the line, “I do perceive here a divided duty,” was replaced by, …, wait for it, … Ulysses Grant, who rehearsed the role but never got his chance on stage, being replaced by a professional actress at the request of Othello.