Symposium Spotlight: What If…The Realities of Civil War Amputation

Welcome back to our annual spotlight series, highlighting speakers and topics for our upcoming symposium. Over the coming weeks, we will continue to feature previews of our speaker’s presentations for the 2022 Emerging Civil War Symposium. We’ll also be sharing suggested titles that you may want to read in preparation for these programs. This week we feature Jon Tracey…

What if Civil War medicine wasn’t as bad as we think it is?

When you think of Civil War medicine, you probably think of a pretty grisly scene (maybe the iconic amputation scene from the movie Glory or the hospital scenes in movies like Gettysburg?). Popular media and public conception of Civil War medicine is an image of brutality. We envision doctors hacking off limbs without painkillers in a dirty hospital and doing so when soldiers didn’t require an amputation, and believe treatments were even deadlier than doing nothing.

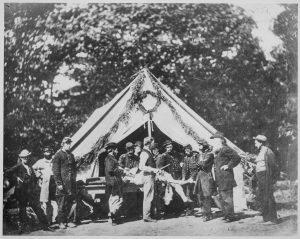

However, Civil War medicine was a lot more advanced and more effective than we give it credit for. Modern images and conceptions Civil War medicine are often a lot different than the realities and improvements shown in primary sources. Throughout the war, surgeons learned how to treat soldiers and professionalized American medicine by sharing what they learned, which led to marked improvement. In addition, as the National Museum of Civil War Medicine makes absolutely clear, 95% of surgeries during the Civil War included the use of anesthesia such as ether or chloroform.[1] Through detailed analysis of treatment records at Gettysburg’s Camp Letterman, possibly the largest tented hospital site during the Civil War, it becomes very clear that by 1863 the US Army’s medical system and staff were prepared and efficient. Though Camp Letterman did not come into being until a few weeks after the battle, the records show what happened to dozens of men who endured these operations, including those who had amputations during the battle.

Medicine has advanced since the Civil War, but many of those advancements were made because of the war. As Shauna Devine explored in Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science, new systems of recording and sharing treatments and results “paved the way for medical knowledge, study, and practice to develop,” and did so through tangible improvement and making doctors “producers of medical knowledge.”[2] In few fields was careful study and dissemination of knowledge clearer than in examination of amputation and what made it successful.

It is worth mentioning that even with all the wonders of modern medicine, similar injuries can lead to amputation. In November 2021, a Minnesota hunter’s firearm discharged into his thigh, damaging bone and blood vessels. The leg was amputated, reminding us that sometimes.[3]

Doctors were often unprepared in the beginning of the war, but how could anyone have been fully prepared? Doctors went from hometown practitioners that may never have seen bullet wounds to treating hundreds of ghastly bullet and shell wounds, but they learned. Accounts of the chaos at the beginning of the war and of bloody hospitals were more dramatic than the quick and marked improvement, and public memory latched onto the drama. Though the aftermath of battle was indeed horrible, doctors were not brutal butchers but instead skilled practitioners that saved lives. Seeing the many successes of surgeons during the war can make one wonder: What if it really was that bad? This talk will present the common image of amputation and contrast it with the realities, using Camp Letterman’s treatment records as a case study.

Find more information on our 2022 Symposium, and purchase tickets, by clicking here.

[1] “Anesthesia in the Civil War,” National Museum of Civil War Medicine, https://www.civilwarmed.org/anesthesia/

[2] Shauna Devine, Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 269, 272.

[3] It is worth mentioning in 2018 a man hunting with a .58 caliber Minie ball shot himself in the arm, shattering a bone. Though this man retained use of his arm, it had to be carefully pieced together with numerous titanium screws and plates. This level of care was simply not available during the Civil War. “Deer Hunter Has Leg Amputated After Gun Accidentally Discharges, Shoots Himself,” MSN.com, https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/deer-hunter-has-leg-amputated-after-gun-accidentally-discharges-shoots-himself/ar-AAQUt0R; “The Civil War’s Latest Casualty: This Reenactor Who Shot Himself With A Minie Ball,” Task & Person, https://taskandpurpose.com/thelongmarch/civil-war-reenactor-minie-ball/

I saw a presentation by National Parks Service that said they could recognize specific surgeons by the saw tracks in the bones of amputated limbs.

Thank you for this article. I didn’t realize that anesthesia was used for 95 percent of surgeries. Just think what more could have done for the wounded if they had had antibiotics.

Indeed – it was rather widespread. Yes, it is sad that antibiotics and germ theory were still a ways off, but it was still pretty remarkable what they could do.