Gettysburg of the West?: The Battle of Glorieta Pass

ECW welcomes back guest author Patrick Kelly-Fischer

More than one Civil War battle carries the nickname “Gettysburg of the West” – Chickamauga and Westport come to mind. But I’ve most often heard it applied to Glorieta Pass, fought in northern New Mexico in March 1862. These battles all share some particular traits: They’re typically the climactic moments of Confederate offensives, among the largest and bloodiest battles of their respective theaters of the war, and often can be framed as a Confederate highwater mark.

While Glorieta Pass was fought by armies only a fraction the size of those involved in better-known battles like Gettysburg and Chickamauga, it had a major impact on the course of the war in the West. This was the climax of Confederate Brig. Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley’s campaign in the Arizona and New Mexico Territories, and the death knell for Confederate dreams of a Southwestern empire.

By early March of 1862, the Confederate star was ascendant in the Southwest. Secessionists had organized their own territorial government for the Arizona Territory, the southern half of present-day Arizona and New Mexico. Sibley had arrived with around 3,000 Texan troops who he would dub the Army of New Mexico, and he had already won one battle against Federal forces.

By their own accounts, the Confederates’ ambitious aim was to take the gold fields of Colorado and California, which would dramatically expand the Confederacy’s ability to pay for the war effort while depriving the Union of that same revenue, and open Pacific ports to circumvent the Federal blockade. One of Sibley’s close subordinates specified that “his campaign was to be self-sustaining,” raising sympathetic troops from across the West while living off of captured Union supplies.1

Their most practical route north from Texas was along the Rio Grande to Santa Fe. This would offer a reliable source of water, and most of the population centers – and therefore the supplies they were intent on capturing – were along the river. The path north was initially blocked by Union Col. Edward R.S. Canby at Fort Craig; advancing north in February, Sibley’s army defeated him at the battle of Valverde, but lacked the supplies and artillery necessary to capture the fort and destroy Canby’s army.

Leaving Canby in his rear at Fort Craig, Sibley continued north to Albuquerque, where he hoped to capture enough supplies to keep his army in the field and continue the invasion. William Lott Davidson, a 24-year old private in Company A of the 5th Texas, wrote after the war, “My special duty was to go to the front and scour the country for food and provisions, as we are about out. Of course, the Federals removed everything beyond our reach and if there was anything to be had for the boys, I’ll get it. The enemy moved everything to eat out of the country.”2

Word of Canby’s defeat quickly made its way north, and Union troops burned most of what Sibley was hoping to secure at Albuquerque. While he found a scattering of supplies to keep his army fed, in part with the help of local sympathizers at Cubero, Sibley’s situation was still tenuous. Advance elements of the Confederate army captured Santa Fe without a fight, but most of the badly needed supplies there had already been hidden or evacuated to Fort Union, the northernmost Union post in New Mexico, near the Colorado border.

Fort Union became a rallying point for Federal forces. In addition to supplies, the territorial government of New Mexico had been evacuated there. More importantly, it was the destination for reinforcements coming from Colorado. Early news of Sibley’s invasion had already prompted 900 men of the 1st Colorado Volunteers, commanded by Col. John Slough, to be sent from their posts in Denver and Fort Lyon.3

The regiment marched the better part of 350 miles from Denver in a matter of weeks. Hearing news of the defeat at Valverde, they redoubled their efforts. According to some sources, they supposedly finished the final 100 miles from Raton Pass to Fort Union in just two days, though this may be stretching the truth in the retelling.4

Despite being bottled up at Fort Craig, more than 250 miles from Fort Union, Canby still attempted to exercise command over the situation. He sent detailed instructions to Slough at Fort Union on the importance of patience, coordinating their movements, and not risking the loss of either post. Slough took one line of this – “While waiting for re-enforcements harass the enemy by partisan operations.” – and stretched it to the breaking point, using it as justification to march toward Santa Fe with 1,300 troops, almost his entire force.5

In Santa Fe, only 100 miles away from Fort Union, the Confederates were also on the move. Certainly it was clear to them that the city wouldn’t be the answer to their supply needs, and they needed to keep moving. As a major outpost, Fort Union was likely to have provisions, as well as being astride the path to Colorado’s gold fields and recently settled cities.

Between Santa Fe and Fort Union is a rough stretch of heavily wooded mountains, broken up by narrow canyons and flat-topped mesas. This stretch had been the site of the Pecos Pueblo and was historically both a crossroads and cultural melting pot, between the plains to the northeast and the desert and Rio Grande valley to the southwest. It was also a natural chokepoint that both sides sought to take advantage of.

On March 24, Maj. Charles Pyron of the 2nd Texas led 400 Confederate troops into Apache Canyon to block the Union advance. While they had gone looking for a fight, they were still surprised on the 26th when they were attacked by the similarly-sized Union vanguard under Major John Chivington of the 1st Colorado, who would later become infamous for his leading role in the Sand Creek Massacre.6

Participants on both sides described the fighting as somewhat confused. The Confederates struggled but failed to establish their first two defensive positions, but eventually fell back to a line stretching across the mouth of the canyon. Confederate sources claim they were able to hold their final line successfully, though Chivington blamed nightfall for not pressing the attack further.7,8

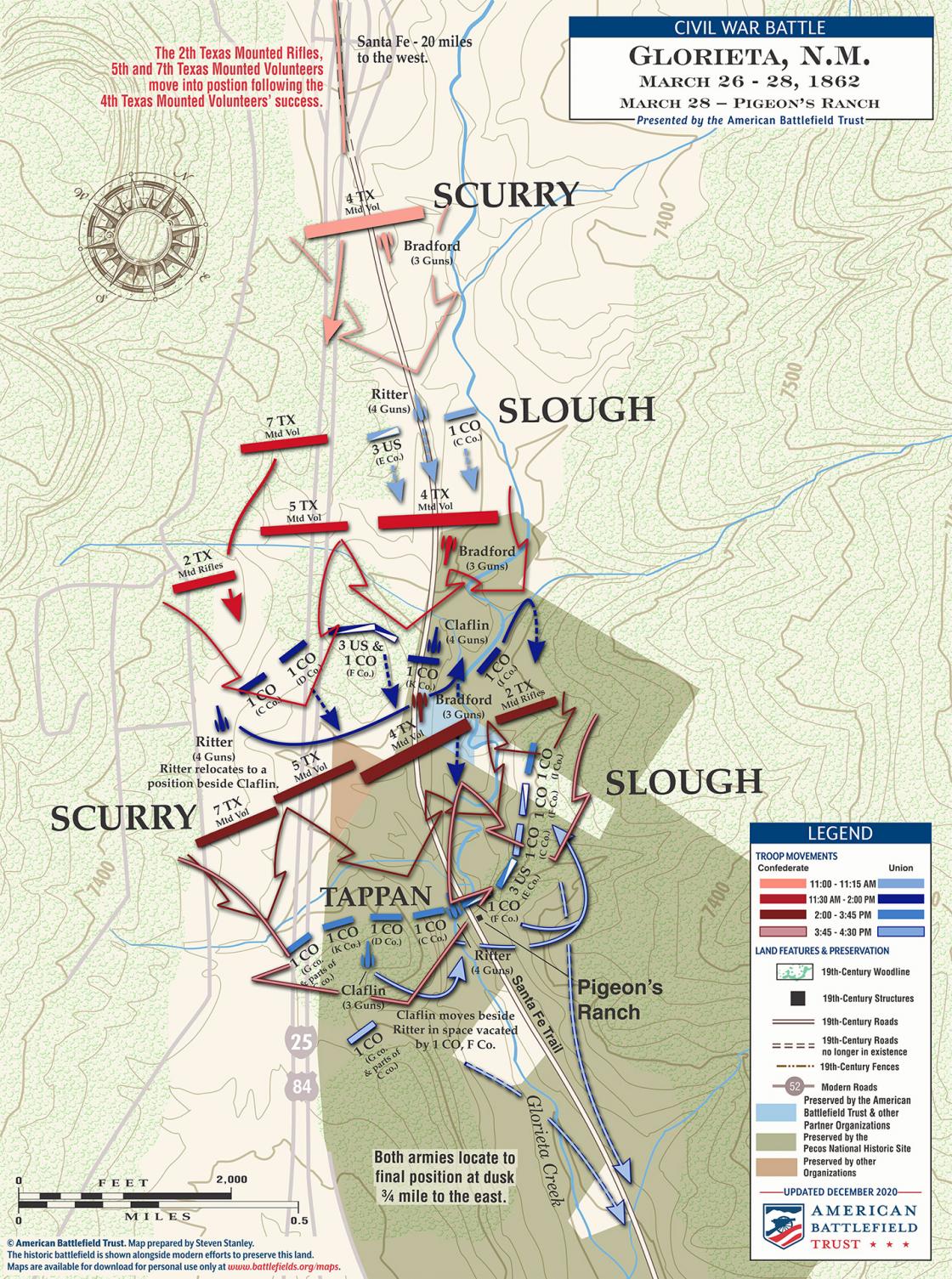

Overnight, Col. William Read Scurry of the 4th Texas arrived with significant reinforcements and took command, bringing Confederate forces to around 1,250, on par with Slough’s 1,300 man army. Throughout the next day, both sides dug into strong defensive positions, expecting the other to attack – and eventually growing impatient, both sides decided to take the offensive on the morning of the 28th.9

They met in Glorieta Pass, 7,500 feet above sea level. Private Davidson of the 5th Texas described the terrain after the war: “We reached a rugged pass between the mountains. Thermopylae was nothing compared to its steep cliffs of rocks with cedar brush on each side of the road. Cliffs were so steep that a man had to get down and crawl up them.”10

Similarly, Slough wrote that, “The character of the country was such as to make the engagement of the bushwhacking kind.” Through about six hours of fighting, Union troops were hard pressed. They fell back repeatedly, but in good order, though you’d never know it from reading Slough’s official reports. As the sun set, they withdrew toward Bernal Springs, in the direction of Fort Union.11

If this had been the only fighting that day, it would likely be remembered as a minor Confederate victory, perhaps one that cleared a path to an eventual rematch with Slough at Fort Union. But unbeknownst to the main Confederate body under Scurry, Slough dispatched Chivington around the pass and around the right flank of the Confederate army. With 400 men scrambling eight miles over rough terrain, without a road, up the towering Glorieta Mesa, by early afternoon Chivington found himself overlooking the lightly guarded Confederate wagon train.12

Charging down the side of the sheer mesa, Chivington dispatched some troops under Capt. Edward Wynkoop of the 1st Colorado to silence the one cannon defending the supply train. Chivington also freed a handful of prisoners taken from Slough’s forces during that day’s fighting, who gave him the impression that Slough was losing. (This is the same Wynkoop for whom a street would be named in downtown Denver, and much later, a brewery founded by now-U.S. Senator John Hickenlooper.)

Chivington finished burning the trains – “The wagons were all heavily loaded with ammunition, clothing, subsistence, and forage, all of which were burned upon the spot or rendered entirely useless” – and then withdrew back the way he came to rejoin Slough. This was devastating to the Confederate army, and was arguably the moment that swung the whole campaign in the United States’ favor.13

Interestingly, 2nd Lt. P.J. “Phil” Fulcrod, a Confederate battery commander, later suggested that the broader Confederate plan was very similar to the plan the Federals executed. He stated that the plan was for Scurry to block the Santa Fe end of the canyon and pass, while Sibley sent six companies of cavalry under Col. Green of the 5th Texas around the Union’s southern flank, where they would block Slough from retreating to Fort Union. According to Fulcrod, Sibley was surprised to learn that days later the battle had already occurred before he could put all of this into motion. This is easier said than done of course, but it was a reasonable plan and offers an interesting counterfactual about how the campaign might have played out.14

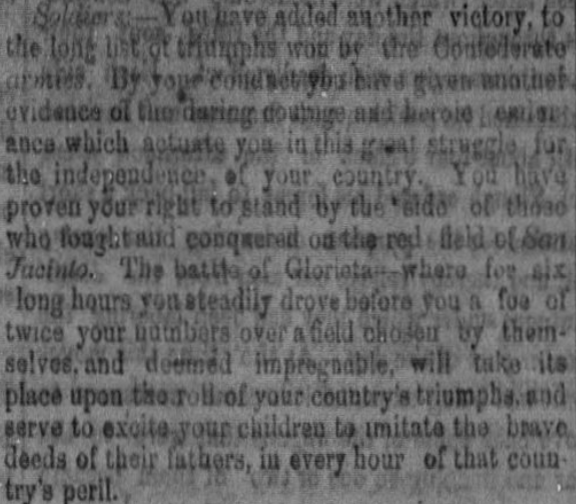

In the aftermath of the battle, Scurry retreated to Santa Fe, where he claimed a victory by publishing a proclamation in the Santa Fe Gazette. But Confederate logistics had been badly overstretched coming into the battle; with the loss of the wagon train, they became a crisis. The Gazette wrote of Scurry’s troops, “All were in the most destitute condition in regard to the most common necessities of life.”15

His proclamation in the Gazette notwithstanding, Scurry admitted the battered condition of his troops in his official report. “The loss of my supplies so crippled me that after burying the dead I was unable to follow up the victory. My men for two days went unfed and blanketless unmurmuringly. I was compelled to come here for something to eat.”16

Davidson painted a similar picture – the two months of desert campaigning had taken a serious toll on the Confederate army. “Old Company A. There wasn’t much of her left. Twenty-three were lost at Valverde, 29 here, 11 gone from pneumonia, smallpox and measles. This only left us 45 out of our 108.”17

In a letter to Richmond on March 31, Sibley tried to paint Glorieta Pass as another Confederate victory. But he was rightfully concerned about Canby’s larger army behind him, Slough’s additional Union forces to the north, and the overall supply situation. He subtly wrote to Richmond, “I must have re-enforcements. The future operations of this army will be duly reported. Send me re-enforcements.”18

Hearing of the battle but not yet knowing the results, Canby also wrote to Washington, D.C. on March 31, expressing grave misgivings that Slough had brought on a battle prematurely.19

A week later Sibley abandoned Santa Fe for good, withdrawing south to face Canby’s forces who were advancing north toward Albuquerque. While there were intermittent skirmishes to come, Glorieta Pass was the end of Confederate offensive operations in the region, and the beginning of a long, brutal retreat down the Rio Grande, through stretches of desert, and eventually back to Texas. Months later, the retreat ended in San Antonio, with fewer than half of the troops returning who had originally set out from there with Sibley.20

Patrick Kelly-Fischer lives in Colorado with his wife, dog and cat, where he works for a nonprofit. A lifelong student of the Civil War, when he isn’t reading or working, you can find him hiking or rooting for the Steelers.

- Major T.T. Teel. “Sibley’s New Mexico Campaign – Its Objects and the Causes of its Failure,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 1888, 700.

- Thompson, Jerry. Civil War in the Southwest: Recollections of the Sibley Brigade. Texas A&M University Press, 2001, 78.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 631-632.

- Nelson, Megan Kate. The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West. Scribner, 2020, 96.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 649.

- Nelson, 104.

- Thompson, 81-83.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 530-531.

- Nelson, 105.

- Thompson, 84.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 533-535.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 538-539.

- Ibid.

- Thompson, 89-90.

- “Military events in New Mexico,” Santa Fe Gazette, April 26, 1862.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 542.

- Thompson, 85-86.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 541.

- United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 658.

- Thompson, 129.

Nice to see solid coverage of the very far western part of the early Civil War. The absence of water and the critical scarcity of food and fuel were always important to 19th century troops, but in most of the land west of the Mississippi they were absolutely essential. I grew up in that country. Tough tough ground to campaign on.

I visited last May. Be sure to buy the $2 map at the National Park for sale at Pecos. I didn’t and all they have are numbered markets along with some placards telling about the battle but without the key you won’t know what happened where the numbers are. Also, very difficult to find and Pecos will give you the combination to the lock to open the gate to the parking area and trails.

I took the car driven tour of the battle with a NP ranger. It was cold and we didn’t really get out and about other than where the Union forces fell back to, and on the side of the road in the pass itself where the main battle was. Definitely couldn’t get out to where Chivington came down, but it was easy to understand what happened that day and about where. Confederates shouldn’t have gone into the pass and just let the Union attack them just to the west of it, where their supply wagons had been. Slough probably would have retreated back to Ft. Union if not to Colorado. Tough men on both sides. Hard country.