On the March to Sailor’s Creek with Tucker’s Naval Battalion

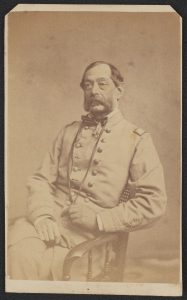

One thousand Confederate sailors and Marines defended Richmond by April 1865. Rear Admiral Raphael Semmes commanded the James River Squadron’s ironclads, wooden steamers, and torpedo boats. The Confederate Naval Academy, officers in training, operated CSS Patrick Henry. Captain John R. Tucker commanded land batteries guarding the James River at Drewry’s Bluff. A scattering of sailors at department headquarters and Richmond’s navy yard completed the list.

Three naval columns departed Richmond upon its evacuation. The Naval Academy midshipmen and Semmes’s men left by train, while Tucker’s command evacuated by foot, joining Robert E. Lee’s retreat and gaining notoriety at the battle of Sailor’s Creek on April 6, 1865. Their participation in that battle was widely documented, but their march much less so. Used to working afloat, one might expect these sailors and Marines to struggle on the march west. Eyewitnesses, however, point to an organized and professional trek.

The Naval Academy’s midshipmen never intended to march out of Richmond. When the capital was evacuated, they boarded trains escorting naval records, politicians, and the Confederate treasury to safety. Their journey ended in Georgia when President Jefferson Davis was captured.

Admiral Raphael Semmes was directed to scuttle his squadron. “Let your people be rationed, as far as possible, for the march” Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory ordered, “and armed and equipped for duty in the field.”[1] The admiral believed his 500 sailors and Marines “incapable of marching a dozen miles without becoming foot-sore.”[2] They instead commandeered an abandoned locomotive at the Richmond and Danville rail yard. Reaching North Carolina, Semmes surrendered with General Joseph Johnston in May.

No one informed Drewry’s Bluff of Richmond’s evacuation. Hearing explosions signaling the James River Squadron’s destruction, Captain John R. Tucker grew nervous. “I am without instructions,” he telegraphed Robert E. Lee, telling the general he would “be happy to learn your wishes concerning this post and garrison.”[3] With no reply he messaged Major General William Mahone, camped nearby, asking “what was going on[?]” Mahone advised him to “follow the movement of the troops … and march.”[4] Captain Tucker acquiesced. On April 3, he mustered his 300-400 men, issued two days rations, destroyed his magazine, and began marching west.

For two days Tucker’s tars marched 30 miles through rain and mud, fighting off occasional cavalry patrols. On April 5, they rendezvoused with Lieutenant General Richard Ewell at Amelia Court House, joining Major General George Washington Custis Lee’s division. Soldiers and sailors alike remembered “many stragglers from the army,” but Tucker’s battalion “did well enough on the march” with few falling behind.[5]

Tucker’s men drew glances from soldiers. Major Robert Stiles was “amused” at how the sailors intermixed “seaman’s and landsman’s jargon” with military orders. “They responded ‘aye, aye’ to every order,” Stiles remembered, “repeating the order itself.” When an army officer offered to help Captain Tucker organize the march, the captain barked back “Young man, I understand how to talk to my people.”[6]

Despite the surprisingly organized march, some straggling occurred. On the sick list and left in Richmond, Midshipman Hubbard Minor reached the rail yard, where he found “several trains & got aboard one.”[7] Marine Corps Major George Terrett was taken prisoner by a US patrol on April 5. Others developed illness on the march. “I was taken with a chill and stopped near the road,” Landsman Robert Watson wrote in his diary.[8] Left behind in Richmond to ensure the naval squadron’s ironclads were fully destroyed, Second Assistant Engineers Eugenius Jack, Joseph Viernelson, and Adolphus Schwartzman hurried to catch up with Tucker.

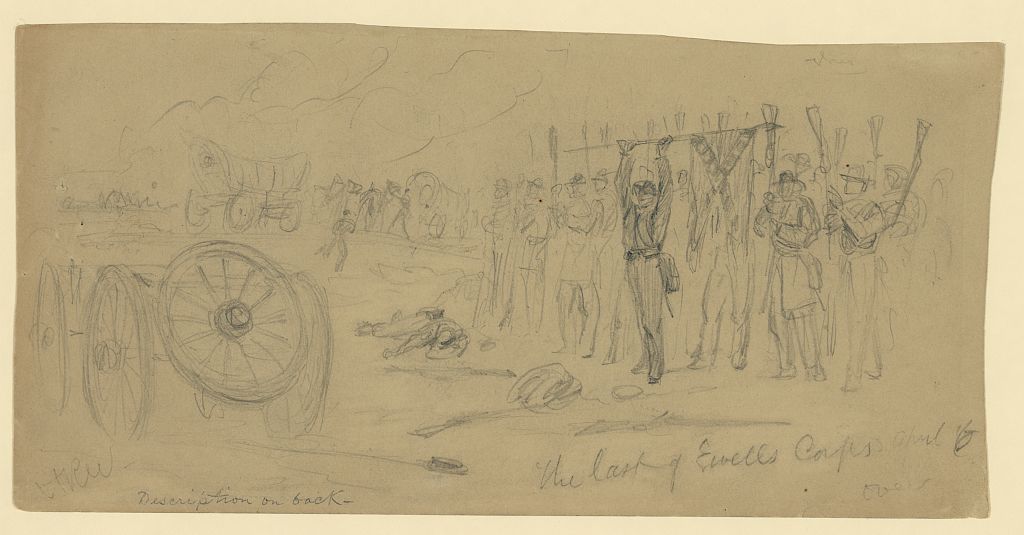

On April 6, the naval battalion fought in the battle of Sailor’s Creek, where the Army of the Potomac attacked General Ewell’s forces “in front & rear capturing or dispersing the whole.”[9] The tars were recognized for fighting “with peculiar obstinacy.”[10] “Those marines fought like tigers” Georgia soldier Daniel Sanford recalled, while a US officer remembered Tucker’s men “clubbed their muskets … and used the bayonet savagely.”[11]

One anecdote about the naval battalion’s performance specifically mentions their marching conduct under fire. Believing he received an order “to take a new position in rear,” Captain Tucker withdrew his men “in a perfectly regular formation.” Staff Officer Howard McHenry was sent to correct Tucker’s unordered shift. The sailors and Marines marched back to the firing line “without a single skulker remaining behind,” something McHenry had never “seen … done as well during the war.”[12]

By nightfall, the naval battalion was surrounded and forced to surrender. Several tars escaped by hiding “in the thick Pines.”[13] Landsman Robert Watson “heard heavy firing” on April 6, as he tried to catch up to the command that was now cut off.[14] He was captured on April 8. Engineers Jack, Viernelson, and Schwartzman were captured on the Sailor’s Creek battlefield’s fringe, still trying to reach Tucker’s battalion. Parole records indicate 108 sailors and Marines surrendered three days later at Appomattox with Lee’s main body.

Several clues hint at how Captain Tucker maintained an organized march amid Lee’s retreat. Most of Tucker’s men had recent extensive marching experience. Marines were permanently stationed at Drewry’s Bluff since 1862, but Tucker’s sailors were survivors from squadrons in Savannah, Charleston, and Wilmington. Captain Tucker himself commanded Charleston’s flotilla until that city was lost. These sailors destroyed their own warships when their respective cities fell, then proceeded north. The remnants of the Charleston and Savannah flotillas marched 100 miles from Florence, South Carolina, to Fayetteville, North Carolina, before continuing to Richmond by rail. On that march, officers strove for discipline, ordering anyone “caught straggling would be tied to the rear of the wagons and made to keep up.” This caused “considerable indignation” amongst the sailors, but the organized march continued.[15]

Another factor was the men themselves. With manpower scarce, infantrymen with extensive marching experience were often transferred to the navy. Among these was Landsman Watson, who spent the first half of the war in the Army of Tennessee.

Another contributing factor was its naval roots. Better supplied throughout the war and unused to the drudgery of land campaigning, many sailors maintained high morale even at the end. A staff officer interrogating two sailors along a road asked what command they belonged to, receiving the reply “To the navy, by gosh, and a bully work it has done.” Out of their element, “the sailors seemed to look up to their officers like children” for guidance and direction.[16] Perhaps they closed ranks with trusted officers out of loyalty, or perhaps it was the desperation of sailors worried about imminent ground combat staying with leaders promising to get them through it all.

Though soldiers commented on the odd uniforms and naval terminology on the march, conceivably military officers were equally as perplexed at how these tars maintained high morale and orderly marching amidst the Army of Northern Virginia’s final trek. Whether it was naval discipline, earlier exposure as infantrymen, loyalty to their officers, a desire to impress nearby soldiers, ignorance of the dire straits they faced, or a host of other intangibles, Captain John R. Tucker’s sailors and Marines managed solid marching and battlefield prowess out of their element.

Footnotes:

[1] Mallory to Semmes, April 2, 1865, Semmes Family Papers, LPR43, Alabama Department of Archives and History.

[2] Raphael Semmes, Memoirs of Service Afloat (Baltimore: Kelly, Piet, and Co., 1869), 812.

[3] Tucker to Lee, April 2, 1865, Robert E. Lee Headquarter Papers, 1850-1876, Mss3 L515 a, Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

[4] William C. Davis, ed. “On the Road to Appomattox,” Civil War Times Illustrated, (January 1971), Vol. 9, No. 9, 7.

[5] April 4, 1865, George M. Brooke, Jr., Ed. Ironclads and Big Guns of the Confederacy: The Journal and Letters of John M. Brooke (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2002), 202; W.W. Blackford, War Years with Jeb Stuart, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1945), 283.

[6] Robert Stiles, Four Years Under Marse Robert, (New York: Neale Publishing Company, 1903), 329.

[7] R. Thomas Campbell, ed. Confederate Naval Cadet: The Diary and Letters of Midshipman Hubbard T. Minor, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2007), 131.

[8] April 6, 1865, Robert Watson Civil War Diary. State Archives of Florida.

[9] Ewell to Mrs. Ewell, April 20, 1865, Donald C. Pfanz, ed. The Letters of General Richard S. Ewell, (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2012), 313.

[10] Wright to Ruggles, April 29, 1865, OR, Ser. 1, Vol. 46, Pt. 1, Section 2, 980.

[11] Daniel B. Sanford, Confederate Veteran, (April 1900), Vol. 8, No. 4, 170; Morris Schaff, The Sunset of the Confederacy (Boston: John Luce and Company, 1912), 107.

[12] McHenry Howard, Recollections of a Maryland Confederate Soldier and Staff Officer, (Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company, 1914), 384.

[13] David S. Woodson to auditor of Public Accounts, September 20, 1917, Confederate Pension Rolls, Veterans and Widows, Virginia Department of Accounts, 1902, Library of Virginia.

[14] April 6, 1865, Watson Diary.

[15] Alan B. Flanders and Neale O. Westfall, Memoirs of E.A. Jack, (White Stone, VA: Brandylane Publishers, 1998), 37.

[16] Howard, 378n, 383.

Thank you for sharing this completely new(to me) story.