An Update and Correction on Edmund Clarence Stedman

ECW welcomes back guest author Max Longley

Here is a brief update to my recent George Gordon post – the abolitionist imprisoned for attacks on U. S. marshals who was released from prison based on a Presidential pardon in 1862.

In that post, I erred by misreading a signature – an error which Professor Jonathan White, author of a related article in the Journal of the American Lincoln Association, graciously reached out to me to address. The post gave the wrong name for the pardon clerk in the office of Attorney General Edward Bates. This was the pardon clerk who recommended that Lincoln grant clemency to George Gordon, not on the broad abolitionist grounds urged by Gordon’s supporters, but based on the disproportion between the sentence and Gordon’s actual guilt.

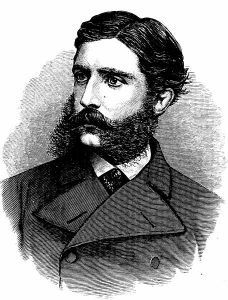

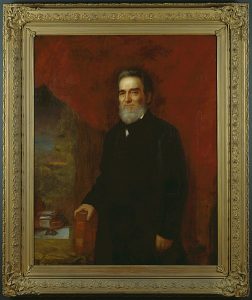

Without repeating my misspelling, here is the the correct name of the clerk: Edmund Clarence Stedman (1833-1908). Stedman is important not only to Civil War history but to the history of American letters. I’ll take a non-chronological approach and take a broad look his life, followed by some brief look at his Civil War experiences, especially so far as they illustrate his attitude toward the Gordon case.[1]

Stedman’s aspirations were toward literature, though he relied on numerous nonliterary day jobs to support himself and his family. Before the war he was the editor of several newspapers, and a real-estate broker. During the war he was a journalist and of course a clerk for Bates. Starting near the end of the war he was a stockbroker, a business he kept at more or less continuously until his 1900 retirement.

His business career had its ups and downs until he received a great personal and financial blow in the 1880s – his son Frederick embezzled funds of the brokerage, and Stedman went into debt, working hard to extricate himself from these embarrassments. Despite setbacks, Stedman seemed, to the outside observer (especially the jealous literary observer) as having made a good living while pursuing the Muse.

Poetry was to Stedman’s literary career what literature in general was to his nonliterary work: the summit to which he aspired while laboring at more financially rewarding work. He wanted to be a serious poet, even an epic poet, though his best successes in verse were satirical or occasional poems in the papers (like this one on Kearny at Seven Pines).

It was as a literary critic and an editor, though, that he earned much of his modern fame. He published a volume of criticism on the Victorian poets, trying to organize his theme in a somewhat scientific manner. He issued a comprehensive anthology of American poems. Goodreads has a list of his works. In the final years of his life, Stedman was known for mentoring younger writers like Edwin Arlington Robinson.

Now, turning back the clock a bit, we’ll look at Stedman during the Civil War.

He covered the early parts of the war as a journalist, even trying to rally retreating troops at the Battle of Bull Run. He welcomed Attorney General Bates’ offer of the clerk position as helping support him in his writing endeavors. According to his own account, he put in a good day’s work in his clerkship even though he could have taken it easy. He was a solid Republican (quitting a remunerative gig at the New York World newspaper when it became firmly Democratic), a supporter of a firm prosecution of the war, while at the same time, for part of 1862, a defender of Gen. McClellan’s generalship until he was ultimately disillusioned. He even took a break from his job with Attorney General Bates to cover McClellan’s Peninsular campaign.[2] His experiences at the front, meeting the soldiers and getting shot at were not as immersive as Ambrose Bierce’s, and did not squelch his romantic conceptions of war as they did with Bierce.

Serving in his Washington clerkship, Stedman wrote a letter to his mother (Feb. 4, 1862) saying something similar to what he would soon write in his Gordon memo: that the North was being very lenient toward Confederates: “But in reading your statement that we are hanging traitors, people at home lift their eye-brows. Not a man has been hung by the North. The War has been hitherto conducted by us with gloves on, and that is the reason we have had no better fortune. Lincoln and Company are afraid of hurting somebody. Probably no war, since the world commenced, was ever waged on such scrupulously false humanitarianism, as this has been by us.” In the same letter, he reassured his mother that he thought religion was a very good thing, at least for women and children.[3] This makes it interesting to wonder what he personally thought of the piety of Rev. Gordon.

Stedman recalled in 1899 that “My chief, Attorney-General Bates, soon discovered that my most important duty was to keep all but the most deserving cases from coming before the kind Mr. Lincoln at all; since there was nothing harder for him to do than to put aside a prisoner’s application, and he could not resist it when it was urged by a pleading wife and a weeping child.” (this, at least, was the message he wanted Joseph M. Proskauer to give “to your East Side boys”)[4]

Between his clerkship and his moving back to New York City for a career in banking and brokerage, Stedman wrote a wartime ballad, Alice of Monmouth. Critics correctly note that this poem, following the life and death of a war hero and the sorrows of his wife and father, is more suffused in sentimentality in the Romantic vein than is strictly appropriate for this particular war, at least.[5]

Max Longley is the author of Quaker Carpetbagger: J. Williams Thorne, Underground Railroad Host Turned North Carolina Politician (McFarland, 2020), For the Union and the Catholic Church: Four Converts in the Civil War (McFarland, 2015), and many articles. He is on Substack (https://maxlongley.substack.com/about) where he is working on articles about various topics, definitely including the Civil War.

[1] For this brief summary of Stedman’s life, I’m relying on Robert J. Scholnick, Edmund Clarence Stedman (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1977.

[2] Laura Stedman and George M. Gould, Life and Letters of Edmund Clarence Stedman, Volume 1 (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1910) pp. 254 ff.

[3] Stedman and Gould, pp. 261-62.

[4] Stedman and Gould. p. 265.

[5] Edmund C. Stedman, Alice of Monmouth, and Idyll of the Great War, with Other Poems (New York: Carleton, 1864), pp. 11-91.

I, for one, appreciate when a researcher or historian or other “fact expert” comes clean and admits they made a mistake: it indicates “awareness of new material; and being receptive to incorporating new, proven information with existing, widely accepted material.”

Thank you for the mea culpa, and for the compelling follow-up report.

Cheers

Mike Maxwell