ECW Weekender: Belle Isle Prison Camp

In the days when I worked in retail, I took a variety of history books to the breakroom. Reading was an escape during my lunch break, but I’m not sure my coworkers always approved of my “light reading.” One of the books had the not-so-lovely title Hell on Belle Isle: Diary of a Civil War POW. After reading this journal of J. Osborn Coburn from Company I of the 6th Michigan Cavalry, I knew I wanted to visit Belle Isle in Richmond and see this place where he spent the final months of his war service and life. This past Memorial Day Weekend I finally had the chance and came away with some emerging ideas to build into my historic interpretation goals.

In the days when I worked in retail, I took a variety of history books to the breakroom. Reading was an escape during my lunch break, but I’m not sure my coworkers always approved of my “light reading.” One of the books had the not-so-lovely title Hell on Belle Isle: Diary of a Civil War POW. After reading this journal of J. Osborn Coburn from Company I of the 6th Michigan Cavalry, I knew I wanted to visit Belle Isle in Richmond and see this place where he spent the final months of his war service and life. This past Memorial Day Weekend I finally had the chance and came away with some emerging ideas to build into my historic interpretation goals.

(Note: this is a different location than Belle Isle State Park on the Rappahannock which I visited a few years ago.)

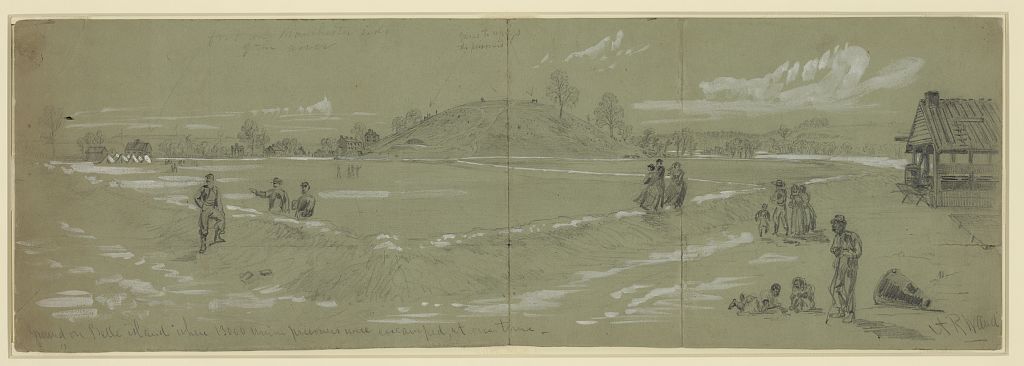

The prison camp opened in June 1862 on an island in the James River, across from Tredegar Iron Works. The 54 acre island had been the property of Old Dominion Iron and Nail Works and some of their factory ruins still remain on the island. Through its history, the prison opened and closed several times, depending on the influx of prisoners and the changing situations with prisoner exchange. The camp closed for the last time in October 1864. In the beginning, Confederate officers planned that Belle Isle Prison would only be a temporary holding location for their Federal captives, but eventually their used it more permanently—sending officers to Libby Prison and noncommissioned officers and privates to Belle Isle. Despite the more permanent nature of the 6 acre prison camp, no major improvements were made for the prisoners’ shelter. Tents, a dead line to prevent escapes, and artillery to deter revolts were the extent of the Confederate efforts at fortifying or building at the prison camp. Captain Henry Wirz oversaw Belle Isle, the same officer who later went to Andersonville, Georgia, and the same officer who was executed for his cruelty to prisoners. His methods and cruelties were practiced and refined at Belle Isle.

Overcrowding at Belle Isle Prisoner of War Camp proved problematic and deadly, leading to disease outbreaks. At the worst times, dozens of Union soldiers died daily and were buried outside the camp without coffins. In addition to a lack of food, shelter, and even blankets during the cold Virginia winters, Confederate guards restricted their prisoners’ activities and punished them for stealing food, attempting to go to the latrines at night, and other actions that could disturb the “order” of the camp. The overcrowding was dire during the winter of 1864, and the prisoners were redistributed to other prison camps further south: Andersonville, Danville, or Salisbury.

Civil War prisons on both sides were notoriously bad, but Belle Isle may rival Andersonville for physical harm to its captives. Photographs of Union prisoners held at Belle Isle show skeleton-like bodies—soldiers who had been through hell on earth and are barely alive to tell their story. In total, 20,000 Union soldiers stayed on Belle Isle during its operational months; 1,000 died at the island camp, and others from the effects of their experience there.

Belle Isle is a grim place, but it is part of Civil War history that should not be forgotten. When speaking of the casualties of a battlefield, that includes the dead, the wounded, and the missing. The missing were frequently “the captured.” What happened to them? Where did they go? What was their experience? Is this part of interpretation that needs to come back into the history shared on the battlefields “where it happened”? I am beginning to feel strongly that it would be helpful to mention where “the missing” on both sides were sent after particular battles. And so, with this in mind and Osborn Coburn’s journal words in my backpack, I headed to the infamous island.

Located in the James River, Belle Isle is now accessible by pedestrian bridge. I parked near the American Civil War Museum and Tredegar Iron Works and walked along the river until I found the sloping rampway up to the walking bridge.

Once on Belle Isle, the first thing that caught my eye was low wooden buildings and some metal structures. The maps and interpretive panels clarified that these were left from post war industry. There are layers of history on this river island. Following the pathway to the right, there are some interpretive signs about the prisoner of war camp.

A little further on, a shady grove covers the prisoners’ cemetery. There aren’t obvious gravestones, but someone laid some large stones in the shape of a memorial cross.

A sort of earthwork line caught my eye next. It looked like a border and I wondered if it had been part of the prison camp or if it was leftover from a later project. A sign confirmed my suspicion: this was the dead line of the prison camp. On the high ground behind it, cannon overlooked the prisoners. Without a stockade, the Confederate guards used the artillery threat and the dead line to contain the prisoners. Anyone caught trying to cross the low earthwork would be shot by the guards.

The land of the prison camp itself was used in later decades for industrial metalwork and is now an overgrown woodland. A short trail loops back toward the pedestrian bridge and across the prison camp location.

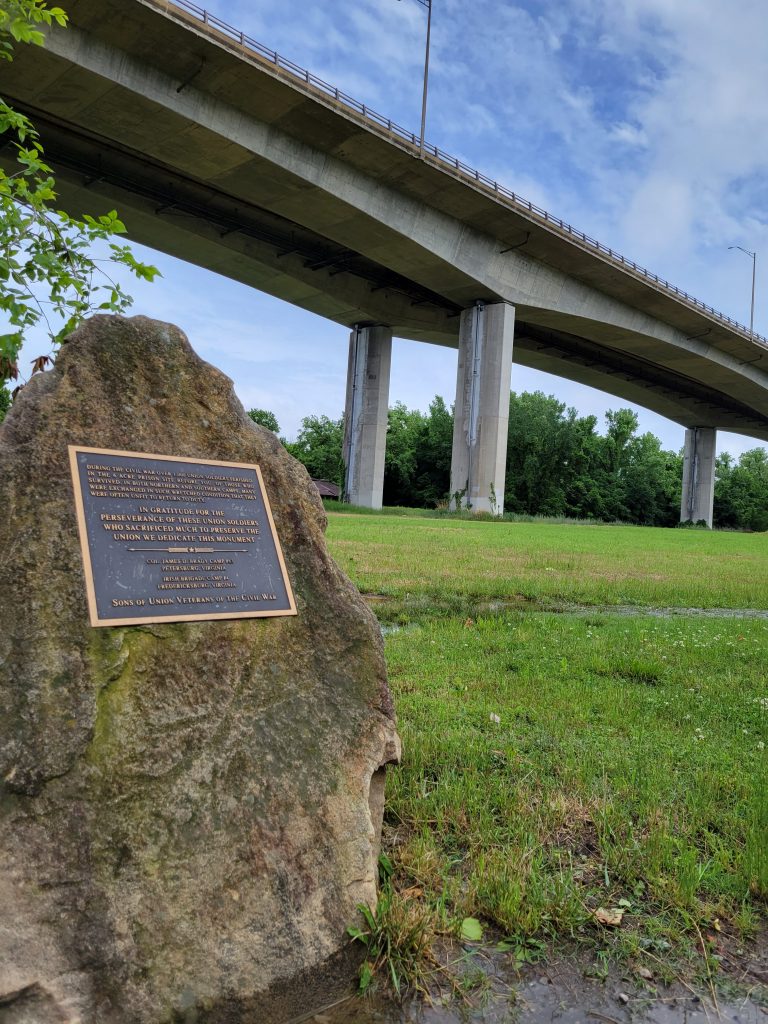

The Sons of Union Veterans placed a memorial plaque and stone along the well-traveled trail, remembering the experiences of thousands of prisoners held at this location.

There are trails that loop further north on the island and according to the map there may be rifle pits on that side. I did not have an opportunity to explore that direction. However, I did climb part way up the high ground where the artillery once sat above the prison camp. The area is now wooded and I found the path rather slippery after the recent rains. My hiking companions were waiting, so I did not poke around to confirm if there were any remaining clues for artillery fortifications.

On New Year’s Day 1864 — after long weeks at Belle Isle — Osborn Coburn wrote:

And we are yet here upon this accursed island. O how many anxious ones here had hopes to have spent this day with their friends at home or at least with friends in our own lines, instead of which we are ragging out a miserable existence as prisoners of war, and I doubt if any prisoners were ever before treated by any people professing to be a civilized nation as are the prisoners here. Thrown into old ragged tents without any bedding, blankets or anything of the kind. Our allowance of food is about a fourth what our government allows us. It is enough so that a hearty man will not actually starve, but not enough to prevent the rapid contracting of disease.

Why, O, why is this permitted[?] I had often been exhorted to place my entire confidence and trust in Providence in all kinds of emergency…. Now we are here. The enemy’s[sp] cannon is in position to rake us at the first indication of a mutiny. There is no opportunity to assist ourselves. Can Providence? Will he do anything to relieve us? ….Well there is yet considerable hope that we shall be relieved soon. So I will not commence to murmur against God and country yet.

Coburn died on March 8, 1864, in Richmond’s Hospital No. 21. His cause of death was listed as diarrhea, and from his journal, it is evident that a chronic form of that illness had been weakening him for months during his time at Belle Isle. He was one of the hundreds who did not survive and changed from “missing” to “dead” because of this island location in the James River.

Today, a highway bridge literally runs over the top of the prisoner of war camp, but enough remains to offer a place for reflection and remembrance.

A metal frame stands near the trail map panel. I think it’s probably leftover from the post war metal works on this location; there’s nothing that indicates its a monument or memorial. Yet, it looks like an artistic impression of a Sibley tent, one of the few forms of shelter given to the Union prisoners here on Belle Isle. It’s been raining and a large puddle has formed beneath the metal. When the stray beams of sunlight catch the water, the metal, the highway bridge, and the sky are mirrored. Layers of history are embedded on this “accursed island,” and now we are here. What do we see? What do we learn? What stories do we take away from this place of captivity, hardship, and death? Belle Isle — like other prison camps — is connected to the battlefields that we walk and explain in writing and in tours. In the coming weeks, I want to think about how to weave the accounts of “the missing” into more teaching moments.

I used to go for walks there during lunch hours. There is a stark contrast between the cemetery with its sadness and the beauty of the James River fall line a little to the right of the picture you took of the cemetery.

Difficult to imagine the inhumanity described in Sarah’s thought provoking piece

My 82d Ohio ancestor survived Belle Island as well as Andersonville, 17 months after being captured at Gettysburg. For his story look up Hiram’s Honor.

I never knew one could actually walk on Belle Isle. Next time I’m up that way, I’ll have to take a walk on the trails.

Had a relative who died of starvation as a Union POW

Thanks for remembering Belle Isle. My great uncle was a POW there. Civil War records indicate he died of Arsenic poisoning. Family lore says he died of starvation. I believe he was buried in the POW cemetery and later exhumed and reinterred at Richmond National Cemetery.

My great-great grandfather was taken prisoner at one of the battles of Winchester and then taken to Belle Isle June 23, 1863 and was paroled to City Point July 8, 1863. He then was transported to College Green Barracks and from there to Camp Parole. He continued to Camp Convalescent and then back to Camp Parole. He eventually returned to his unit (12th West Virginia Volunteer Infantry) to continue to fight. He was in the battle at Appomattox and a witness to the surrender at Appomattox courthouse. He died at the age of 73. He was a very lucky man.

My Great-grandfather, John Hoffman was at Belle Isle after being captured and then was sent on to Libby, Andersonville and other prisons. The following is a short account of his experience.

Dec 15 1862, enlisted in Company W 8th Michigan Cavalry, first being corporal and then sergeant.

While the army was at Dandridge, Tenn. on January 18 1963, John with three others was sent with dispatches from Gen Burnsides headquarters to Colonel Genard some fifteen miles distant and John and his companions were taken prisoners.

They were taken before Gen Longstreet and sent to prison, first to Belle Isle, then to Libby, then Andersonville, next to Florence and lastly to Charleston.

John was in prison fifteen months, seven months of the time in Andersonville.

His three companions died in prison.

John suffered terribly from prison life and it was only his then good constitution and a heap of grit that enabled him to survive.