Unpublished: What’s Not in the O.R.s?

As Walt Whitman famously said, “The real war will never get in the books.” When I think if “unpublished sources,” I start wondering broadly about what never made it into print. As this series has demonstrated, there’s a ton of unpublished gold available to researchers who take the time to dig for it.

As Walt Whitman famously said, “The real war will never get in the books.” When I think if “unpublished sources,” I start wondering broadly about what never made it into print. As this series has demonstrated, there’s a ton of unpublished gold available to researchers who take the time to dig for it.

But as I started ruminating on this topic, I kept going back to the Civil War researcher’s “old faithful,” the Official Records. They are, quite literally, the government’s official account of the War of the Rebellion (their title!). But I invite you to consider something about the O.R.

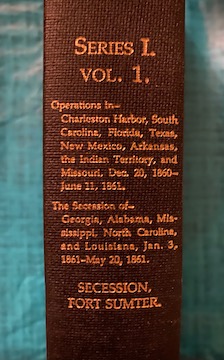

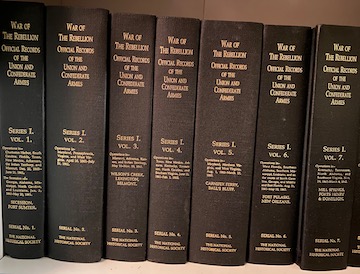

One of the (many) things that amazes me about the O.R. is that we can literally see how the armies—and the Union army, in particular—learn to record-keep. Volume 1, Series I is a mere 752 pages long, including index, and if covers Dec. 20, 1860-June 11, 1861, including “Secession” and “Fort Sumter.”

By the Richmond and Appomattox Campaigns of the spring of 1865, Volume 46 spans three parts over 4,535 pages. Chronologically, Series I of the O.R. winds down with Volume 50 in two parts, totaling 2,663 pages, covering “Operations on the Pacific Coast” (did you realize there were more than 2,600 pages of action on the Civil War on the Pacific Coast?).

Series I then caps off with Volumes 51-53, which all contain supplementary documents “found or received too late for insertion” in earlier volumes.

And this is where I start thinking of Uncle’s Walt’s comment about the real war not getting into the books. Look how much documentary material exists from later in the war as compared to earlier in the war, as reflected by the O.R.s.

And this is where I start thinking of Uncle’s Walt’s comment about the real war not getting into the books. Look how much documentary material exists from later in the war as compared to earlier in the war, as reflected by the O.R.s.

We think of the evolution and improvement of technology over the course of the war. We think of tactics, medicine, communication, transportation. Advances in all of these fields led to tremendous growth. We see, too, the way men like Lincoln and Grant evolved over the course of the war. Record-keeping was no different. And as the armies improved their record keeping, the documentary evidence they generated—and kept—grew exponentially.

And let’s not forget, in instances like the Overland Campaign, the Atlanta Campaign, and Sherman’s March to the Sea, officers had less downtime time to sit and write. Many officers got killed off before they had the chance to even write their reports, so those reports went unwritten or they were written in an abbreviated form by a replacement. Even with those sorts of limitations, the armies still generated a tremendous amount of paperwork.

On the flip side, we can also see all the source material that didn’t make it into the books for various reasons.

Let’s also not forget the vast number of records lost when Confederates burned Richmond on their way out of town in April 1865. While a number of records were saved, many weren’t. Yet despite that diminished trove of documents, we still have huge O.R. volumes toward the end of the war. Imagine if all Confederate records had been saved—imagine how much more complete, and how much more formidable, those late-war volumes would be, crammed fuller with Confederate material.

Compare those hulking late-war volumes to the sparser volumes from early in the war. What didn’t get written down because the army and its officers just hadn’t figured out yet what sorts of things needed to be written down? The processes and procedures and protocols for collecting info and generating reports hadn’t been formalized or even yet developed. In theory, those early war volumes could have been every bit as robust as late-war volumes.

What material didn’t get published because it never got written in the first place?

The creation of the ORs is, itself, a fascinating story. The project got underway during the Grant administration—a true example of “history is written by the victors” if ever there was one. The editorial process of deciding what was in and what was out and how it was all organized also impacted what made it into the record. (Joan Waugh has a fascinating essay that talks about this in her book U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth.)

As our “Unpublished” series has pointed out, a number of other resources exist for catching a look at those parts of the war that didn’t get into the books, so we do have ways of fleshing out some of those lesser-written-about periods of the war. But this notion of unpublished sources that were never written in the first place—never written for all sorts of reasons—it intrigues me. Our understanding of the war itself has been shaped by the act of recordkeeping.

What parts of those records, what parts of the war, never made it into the books?

Chris,

I am surprised that you didn’t mention The Supplement to the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies published by Tom Broadfoot and the Broadfoot Publishing Company. This publication added an additional 100 volumes of information to the original Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion, and clearly illustrates “What’s Not in the O.R.s.”

Bob Murrell…

Thanks, Bob. That’s a good point (and a good collection of material worthy of its own post!). I was really trying to focus on how the historical record was impacted in real-time during the war, with a nod toward the impact the post-war assembly also had. Broadfoot’s Supplement is a layer of reconstruction that goes even beyond that. Good call.

One of your best posts! If only Shaw, or Kearney, or Sedgwick ( or Jackson, Ramseu and Stuart) had survived. But that was war….

Thanks!

Back in the 1990s I did research in order to create the supplement to the official records. I found out that there were two entry groups for official records material. The second group closely paralleled the arrangement of the actual volumes. The other entry group contained huge amounts of material that never had found their way into the official records. And, unfortunately, we did not include it either. If it’s OK with you guys I’d like to say more about this project in another comment

Please do!

The National Archives is loaded with important, primary material that never made it into the O.R.’s. For example, RG 393 is full of valuable data about the various military departments and army corps. Volunteer service records, pension files and soldiers’ compiled service records also contain additional material. In my research for a multi-volume work about the 14th New York State Militia (14th Brooklyn), I was lucky enough to go through all of those records (and more) before the NARA shut down due to Covid.

My friend Robert Lee Hodge loves to talk about the boxes and boxes of unindexed, essentially uncatalogued material up there in boxes and boxes and boxes labeled “miscellaneous.”

That history of the Fighting Fourteenth is one to look forward to!

Thanks for initiating this discussion of “the problem with the ORs.”

“The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies” began being published (available to the public) in 1881; and the full set of “Armies” material was available by 1901. While this slow release of “Armies” material was bad enough, the publication of “Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion” was even longer delayed, with their publication spanning 1895- 1915.

Why is this “tardy publication” important?

Nature abhors a vacuum. For many years, the only “accepted history” was soldier’s memories, archived newspapers, and a few select biographies. Many early attempts to “connect the dots” gained acceptance, and persisted, even after publication of the ORs and OR(N)s: “a lie will travel twice around the world before Truth gets his boots on.” We still struggle to correct assumptions made during that 1865- 1881 period of “bad history” to this day.

These limitations need to be borne in mind when critiquing pre-OR publications and condemning any seeming discrepancies. This caution particularly applies to the so-called “Lost Cause” material, much published prior to the availability of the OR. Robert E. Lee himself delayed compiling memories of the War due to difficulty in accumulating accurate material on which to draw, and his stroke intervened before much could be done.

I’ve been collecting individual volumes over the years and its fascinating to crack one open and read the correspondence. Its almost like experiencing the war in real time. The one that stands out for me was messages being passed between Meade and Burnside while the battle of The Crater was raging.

I am reminded of the vast amount of documentation lost on July 29, 1864, when BG Ed McCook’s cavalry division burned the (500) wagons of the supply and baggage train of the Army of Tennessee. Regimental muster rolls and returns were destroyed. Research on men in that organization can be pretty scant. Guess McCook got what he deserved, as did Stoneman, in this episode.

A huge treasure trove is the diaries and letters of soldiers which are in obscure archives or even still in private/family collections.

It would be ideal if the Official Records were a “one-stop shop” for Civil War researchers, but the compilation of those records, early on, involved “determination [by someone] of ‘what was important (and included)’ and ‘what was unimportant (and left out).’” For example, some personal letters are included; while most personal letters are left out. And the early attempt to “organize the entire Official Records by TIME” failed with the introduction of Supplements incorporating new material, which then required creation of an INDEX in order to find that new material (and that Index was incomplete.) Access to the ORs and OR(N)s via the internet, with ability to Word Search has restored the usefulness of the Official Records to researchers in recent years, but there are some failings that will never be resolved.

One failing is “the absorption and consolidation” of regiments that occurred during the whole of the Civil War. Sometimes, this official amalgamation of two or more regiments, with new numeric designation, is included in the records; but more often, it is not. When it is not, the researcher must track down that information via some other reference. In the case of Alabama regiments, that information is available in “Brewer’s Alabama,” beginning page 589. Actual title is “Alabama, Her History, Resources, War Record, and Public Men, From 1540 to 1872” by Willis Brewer and available online https://archive.org/details/cu31924028794042/page/588/mode/1up?view=theater

Great post, Chris. To illustrate your point about things simply not being published in the OR, I found a map at the Nat’l Archives that was referenced in Thos. Ruger’s report (asterisked by the OR compilers as not included) for Cedar Mountain. For me, this map was the final straw for re-interpreting the 3rd Wisconsin’s initial fighting at that battle.