“Everything seemed ablaze around me”: Albert Baur and the 102nd New York at the Battle of Cedar Mountain

ECW welcomes back guest author Douglas Ullman, Jr.

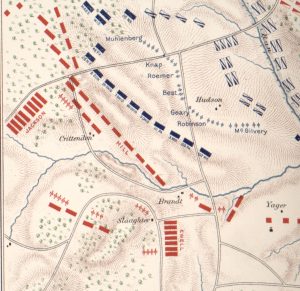

Fifty-three year-old Albert Baur was not going to be able to attend the 1892 reunion of his regiment. The gathering of veterans of the 102nd New York, was set to occur at Cedar Mountain, where they had experienced their first trial by fire. He was sitting in his office, ruminating over the “thrilling incidents of the camp, the march, and of that bloody, shell and bullet-ridden field in Virginia” when someone handed him “an Atlas, a part of the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion.” Baur opened it up and immediately landed on a map of the Cedar Mountain battlefield. “It was a strange coincidence,” Baur wrote, “sitting there and dreaming over the scenes enacted on that field, and then, without any warning have someone hand me the official documents to help me out in my wanderings.” The map was of particular interest to him. “I never before knew why it was that our regiment was overwhelmed and nearly annihilated. A glance at the map explains it all and makes everything clear in my mind.” Memories flooded the aging soldier, who spent the rest of the night thinking about the battle and the next day wrote to his old commander, Lewis Stegman, to share a story that had not made it into the Official Records.

The 102nd New York arrived in Culpeper, Virginia, on the night of August 8, 1862, after an exhausting all-day march in the sweltering heat. Lieutenant Aaron Bates of Company D thought the heat “was hotter than anything I have seen [in the] north.” The next day was even hotter and several men, including Bates himself, were “overcome with the heat” and found themselves lying by the roadside. Their brigade commander, a West Point graduate and a veteran of the Mexican War named Brig. Gen. Henry Prince, paused the march in a strip of woods to allow men to refill their canteens and give stragglers a chance to catch up. Before long, the distant thud of artillery fire indicated that the 102nd would have its long-awaited baptism of fire. General Prince informed the men that they would soon meet the enemy “and everyone was expected to keep his place.”

When the march resumed, the regiment left the shelter of the woods and “came to an open field on the left of the road.” As he marched, Baur watched as “some shells of the Rebels scattered a regiment of cavalry which had taken position in the field.” The horsemen bolted, but the rookie New Yorker infantrymen pressed on—toward the danger—and filed off the road. They moved into a hollow and halted near the Hudson House, just behind several batteries of Northern artillery who “were having a duel with those of the Rebels.” Others in the regiment estimated the barrage went on for some two hours and was enough “to set a man Deaf” for the rest of his life. Baur recalled only that he laid down near the Hudson House for “a considerable length of time,” at which point General Prince “rode up in our front and ordered us forward.”

Placed in line of battle, the 102nd formed the extreme left of the Union attacking force at Cedar Mountain. To their right was the 109th Pennsylvania and, beyond that, the rest of their division. To their left was nothing but the rolling countryside of Culpeper county and the towering height of Cedar Mountain. The regiment moved forward, through the still-firing artillery pieces and stepped into a plowed field. As they passed the guns, Baur heard the general announce, “There is no one in front of you but the enemy.” He saw “bullets throwing up the dirt” in the plowed field in front of them. Beyond that, a field of tall corn obscured nearly everything from view. When the order to advance came, the 102nd entered “the seething, burning, hell-ridden cornfield, where the screech of the shells, the ping of the bullets and shouts of the men, together with the fearful havoc in our ranks, made it possible to imagine oneself in a veritable hell with the concomitant devil and all his imps.”

Upon entering the field, Baur could only see “shell and bullets coming from the direction of the Rebels.” Believing that only the enemy was in their front, the New Yorkers aimed their rifles blindly into the corn, “firing rapidly, at will.” A moment later, murky forms moved toward them through the stalks. “In the smoke and excitement,” Baur “saw many of our men firing right into those coming towards us” only to discover “that we were firing into Eighth and Twelfth Regulars” who had been acting as skirmishers in front of the brigade. Clutching wounds to his head and back, a bearded lieutenant complained to Baur: “My God, it is hard to be shot by your own men.” Several more disgruntled regulars likely passed through the One Hundred and Second’s ranks before the New Yorkers continued their advance.

Advancing through the corn, the 102nd crested a slight ridge, where the men “were fearfully mowed down.” The New Yorkers dropped to the earth “and the battle raged in earnest.” In Baur’s Company A, Corporals Jim White and Richard French were “[a]mong the first to fall.” French “had been shot in the left breast with a piece of ramrod.” The wounded corporal sat up and extracted the rammer from his own chest as he told Baur, “I am killed, have me carried off.” He laid back down, “straightened himself out and I suppose waited to be carried off.” Nearby, 19 year-old Joe Donnelly writhed on the ground with a painful wound to the groin. “He turned himself on his back” which apparently gave him comfort enough to wait for his own evacuation. Turning from his wounded comrades, Baur knelt amidst the stalks of corn and continued firing. In the meantime, General Prince rode along the line and advised the New Yorkers they were crowding the regiment’s to their right. “He rode towards the left of the regiment,” remembered Baur, “ordering the One Hundred and Second to ‘give way to the left,’” when he disappeared into the corn, and into the hands of waiting Confederates.

Albert Baur was still on his knees, blazing away at Confederates, when he “noticed but few of our men, and those that I did see were retreating.” He came to his feet, turned to the rear, and stepped over the prostrate form of Joe Donnelly. “For God’s sake, Al,” cried the wounded Donnelly, “do not leave me, take me along.” The battle seemed to be raging all around them and Baur “feared we would hardly be able to get ourselves out.” He grasped Donnelly by the hand and promised to come back “if we were not surrounded.”

Moving just a short distance, Baur saw “a flag lying on the ground”—the national colors of his regiment. The body of another Company A man, Corporal William Lawless, lay on top of it. Baur rolled Lawless’s lifeless form off the banner, lifted it from the ground and “started again” for the rear. Almost immediately, Confederates began to call on him to surrender. A combination of growing darkness and “dense smoke made it quite dark in the cornfield” so Baur ignored their demands “but started back as fast as I could jump.” In his haste to get out, he must have gotten turned around in the corn. He emerged from the field and “ran right in front a Rebel line of battle” coming from what had been the left of his regiment. “Everything seemed ablaze about me,” he recalled, “and I ran first one way, then another” as enemy soldiers passed him on every side. Looking back in 1892, Baur couldn’t imagine “how I ever escaped being shot as full of holes as a colander.” But escape he did, finding the Hudson House, where their assault had begun. There he found his own company commander, Captain Robert Avery. The exhausted Baur “gave Captain Avery the flag and asked him to give it to some one else.”

The battle exacted a fearful toll on the 102nd New York. Unfortunately, because of straggling due to heat exhaustion, it is difficult to know for certain how many men the regiment took into battle. Lieutenant Bates estimated that approximately 200 New Yorkers entered the fight on August 9. Of those, 115 became casualties, including 15 killed. Among those to survive was Corporal Richard French, who after pulling a ramrod from his own body managed to beat Albert Baur to the rear. “I do not know when he left the field,” wrote Baur, but “he could not have been badly ‘killed’ if he could beat me running.” French survived the wound and was discharged in December. Joe Donnelly was not so lucky. He was apparently recovered from the battlefield but died of his wound. The loss in officers was particularly high, with nine officers wounded and one officer killed out of the 20 engaged. Seeing the map printed in the Official Records helped Baur make sense of all this. Writing in 1892, he realized “the One Hundred and Second was nearly surrounded, for they were marched right into a pocket formed by the Rebel lines.” Despite these overwhelming odds, these rookie soldiers from the Excelsior State stood their ground and fought until compelled to leave the field.

In summarizing his actions, Albert Baur explained that he “lost all control over my every action except the desire to escape and carry the flag with me.” Many Medals of Honor were awarded to Civil War soldiers for displaying this very same devotion to their colors. One can only wonder if Baur might have received the nation’s highest honor if someone had recorded his actions at the time of the battle. Indeed, much of the fighting on the left wing of the Union army was overlooked at the time and, even today, the majority of scholarship emphasizes the northern and central parts of the battlefield—to say nothing of a single Confederate general named Jackson. This is really a shame because Baur’s account is one of several that reveal the chaos and courage that attended the fighting on the Union left. Though none of them made it into the Official Records, they are nonetheless deserving of recognition. Fortunately for us, the State Historian of New York State published Baur’s letter to Stegman in its annual report of 1897, allowing future generations to learn of his heroism and that of his regiment.

Doug Ullman, Jr. has written numerous pieces for America Battlefield Trust and frequently contributed to their Civil War in4 and War Department series. He is a graduate of New York University’s Steinhardt School.

Sources:

– Albert Baur, “A Very Close Call for the Colors” (Appendix E), Second Annual Report of the State Historian of the State of New York (1897), pp. 111-117

– Aaron Bates, “The Battle of Cedar Mountain” (Appendix D), ibid, pp. 101-108

– Report of Brig. Gen. Henry Prince, Official Records, Vol. XII, Part 2, pp. 167-170

– Michael Walsh Letter to Wife, August 16, 1862, Michael Walsh Pension File, Widows Certificate No. 274771, National Archives)

Excellent article! Thank you for sharing this common soldier’s incredible story.

thanks Doug … great essay … those first-hand combat accounts are sobering and your map shows the 102nd was in the hot corner.

here’s a few nuggets on 102nd from “New York in the War of Rebellion” from 1912 … called the Van Buren Light Infantry after their commanding officer, Thomas A. Van Buren … the regiment was from NYC, Brooklyn and Jersey City.

Baur’s Co. A. was an NYC a militia company called 12th Militia, Avery Rifles, Independence Guard after their commanding officer Robert Avery … Avery was wounded at Chancellorsville and again at Lookout Mountain … Avery was mustered out due to his wounds in June 1864 and served in the Veteran Reserve Corps (invalid corps) … he was breveted to MajGen in 1865 … the other officer Baur mentions, LT Aaron Bates, from Co. D., was KIA.

In the east, they were part of the XII Corps and were heavily engaged Cedar Creek and Chancellorsville where took about half their wartime casualties of 439 … after Gettysburg, they went west with Hooker and were eventually part of the XX Corps … they finished the war in the West.