Book Review: The Wharton’s War

Gabriel Colvin Wharton, Virginia-born in 1824, ranks among the Confederacy’s 425 generals, but not among those best-known.

Gabriel Colvin Wharton, Virginia-born in 1824, ranks among the Confederacy’s 425 generals, but not among those best-known.

Or illustrious, for that matter, despite a colorful Confederate career. VMI-trained, he was elected major in the 45th Virginia. He then raised the 51st and became its colonel in mid-July ’61. He fought at Carnifex Ferry two months later. Wharton was sent to Fort Donelson, but before the surrender fought his way out. He returned to southwest Virginia and took charge of an infantry brigade. He was in command at Winchester when Lee raided into Pennsylvania, yet Colonel Wharton chafed at commanding a brigade without commensurate rank.

Along the way, in May 1863, he married Anne Radford. It was during their courtship that these letters began to be exchanged. “Will Miss Nannie pardon the intrusion of this my little Messenger?” Gabe’s first missive begins, reminding us just how cute and quaint nineteenth-century epistolation can be. But things got complicated when Anne urged her husband to seek promotion. She admitted that “the ruling passion of my life” was ambition. “I truly believe that as far as our happiness in life is concerned we had both better be dead than to drag thro life unknown & unhonored,” she once wrote. Gabriel reciprocated by attesting that his love would be measured by their dream-realization; Wharton was confirmed as brigadier in February of ’64.

When Wharton fought at New Market, the VMI cadets were attached to his brigade, whose final charge sent Sigel packing. After Lee summoned Breckinridge, Wharton fought at Cold Harbor. “There was a general attack this morning & the Enemy were driven back with terrible slaughter,” Gabe wrote Nannie on June 3; “Grant’s demoralized troops will not be able to face Genl Lee’s army much longer.” Campaigning with Early to Washington, Wharton wrote his wife that he had gotten close enough to see the dome of the Federal capitol. Later, he fought at Cedar Creek and shared in Confederates’ exultation at their initial success. “But unfortunately they recd. re-enforcements in the evening & drove us back,” he explained to his wife, “hurriedly & in confusion.” Nannie responded predictably: “From all accounts Early must have been whipped indeed. I don’t like so much whipping.” Wharton was with Early to the end. He was paroled at Lynchburg in June of ’65.

Jack Davis is well known to Civil Warriors. Sue Heth Bell is the Whartons’ great-great granddaughter. She discovered these letters in (I’m not kidding) her parents’ garage. The editors provide extensive introductions to their twenty-seven chapters, offering an intriguing biographical narrative to their correspondents’ missives.

Gabriel Wharton died in 1906, before which he had written, “When I am dead burn all these letters & every thing else.” As Davis and Bell conclude, “Thankfully, no one heeded his instructions.”

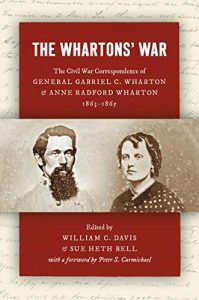

The Whartons’ War: The Civil War Correspondence of General Gabriel C. Wharton & Anne Radford Wharton, 1863-1865

Edited by William C. Davis & Sue Heth Bell

University of North Carolina Press 2022 $45 paperback

Reviewed by Stephen Davis

thanks — what a great find by the Bell family … and now we get to see it — very cool … there’s a term for a general officer’s wife like Anne these days … folks would refer to her as “wearing her husband’s rank” … not a compliment.

Thanks for sharing and a new book to add to my library. Wharton is a well known industrial equipment supplier in Virginia. I’ve passed by their business’ and often wondered if from the same confederate lineage. The Wharton and Radford family connection is also little known outside of civil war circles. I find these family connections intriguing and their importance to how our country in the south reconstructed itself after the war.