“Here I am . . . a Prisoner:” The Capture of Walt Whitman’s Brother

Siblings sometimes produce interesting relationships. In many cases, the younger moves through childhood and into the teen years aspiring to be like the elder. I know that, personally, although my older brother and I fought like cats and dogs growing up, a large part of the conflict was due to my petty jealousy of his abilities and successes. It was not until I came to realize that I had useful talents of my own that we truly became close. However, in the relationship between siblings Walt Whitman, and his younger brother George Washington Whitman, the older appeared to revere the younger, especially during the Civil War years.

Walt Whitman, born in 1819, was in his forties when the American Civil War began. Younger brother George, born a decade later, was much closer to the age for service in the United States army. George, still single at the time, enlisted in the 13th New York Militia (a three-month unit) in the weeks following Fort Sumter, leaving Walt as the primary caregiver to their aging mother Louisa in Brooklyn. When George’s brief enlistment ended, he joined the 51st New York Infantry.

Growing up, George Whitman received part of his formal education from his older brother. George then learned carpentry from his father, building houses and working long hours in the family trade. George never seemed impressed with older brother Walt’s literary ability or his seemingly deficient physical work ethic. Years later, George explained that, “We were all at work—all except Walt. But we knew he was printing the book [Leaves of Grass]. I was about twenty-five then. I saw the book—didn’t read it all—didn’t think it worth reading—fingered it a little. Mother thought as I did—did not know what to make of it.”

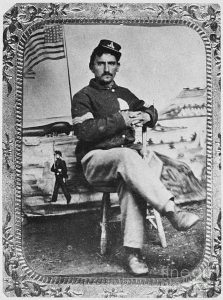

Walt, however, seemed to idolize his younger brother, especially after George committed to going off to war to fight for the Union. George often wrote to his mother and brothers while campaigning with the 51st New York. Entering as a private, George attained the rank of major by the time he mustered out in 1865. Walt later wrote admiringly of his brother’s enlistment: “Like many other young men, he then knew almost nothing of military discipline or practical soldiering; but the great Union call sounded, and he quietly but promptly put away his tools, locked up his chest, put the key in charge of the boss, and betook himself to the field.”

George and the 51st fought valiantly as part of Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s expeditionary force to the North Carolina coast. Then, as part of Burnside’s Ninth Corps, they fought at Second Manassas and Antietam. At the Battle of Fredericksburg, George received a facial wound. Walt read about George’s wounding in the newspaper, and under deep concern, immediately went to Washington, and then to the Fredericksburg area Federal camps to check on his younger brother. “When I found dear brother George, and found that he was alive and well, O you may imagine how trifling all my little cares and difficulties seemed—they vanished into nothing,” Walt later wrote.

George Whitman’s 51st New York was one of the most traveled regiments of the war. Following Fredericksburg, they were transferred to Kentucky, and then to Vicksburg and Jackson, Mississippi, then back to Kentucky. In the spring of 1864, the 51st returned to Virginia and as part of the recombined Ninth Corps, fought in the Overland Campaign alongside the Army of the Potomac. Finally moving to Petersburg in the summer of 1864, the 51st New York battled in the trenches, and participated in the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864.

As part of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s late September 1864 offensive, the Ninth Corps, now under Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, moved to the left end of the Union line to work in cooperation with Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s Fifth Corps. Combined with Federal offensive efforts north of the James River, which resulted in significant victories by the Army of the James at New Market Heights and Fort Harrison on September 29, the Fifth and Ninth Corps received orders to push north from near Poplar Springs Church, just southwest of where the Fifth Corps succeeded in cutting Weldon Railroad (Globe Tavern) back in August.

In the battle that resulted in being called several names—Poplar Springs Church, First Battle of Jones Farm, Squirrel Level Road—but most popularly, Peebles Farm, on the morning of September 30, Warren’s Fifth Corps moved out first. Meeting little resistance from cavalry, they breeched the Confederate fortifications at Squirrel Level Road and then captured Fort Archer (later renamed Fort Wheaton) and began digging in. Parke’s Ninth Corps then moved just to the left of the Fifth Corps and pushed forward with the goal of cutting the Boydton Plank Road, one of the Confederacy’s last two supply lines coming into Petersburg from other parts of the South.

While maneuvering through the fields and woodlots of the Peebles, Pegram, Albert Boisseau, and Robert Jones farms, the First Brigade (Col. John I. Curtin) of the Second Division (Maj. Gen. Robert Potter), Ninth Corps, received a major counterattack by four Confederate brigades, two each from Maj. Gen. Henry Heath’s and Maj. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s divisions, who advanced south down Church Road. With Curtain’s Brigade’s first line, consisting of the 51st New York, 58th Massachusetts, and 45th Pennsylvania’s attention drawn toward the brigades of the Confederates to their right, other Rebel regiments under Brig. Gen. William MacRae hit the right flank of Curtin’s second line composed of the 48th and 21st Pennsylvania, and 36th Massachusetts, throwing the whole brigade into confusion.

The historian of the 58th Massachusetts explained, “the enemy discovering our failure of connection, took advantage of it, and completely surrounded the troops in that locality, and closing every avenue of escape.” He reported that 8 commissioned officers and 91 enlisted men of the regiment became prisoners, leaving only two officers and 75 enlisted men. The history of the 36th Massachusetts tells that, ”the regiment could hold its ground but a short time under the demoralizing effect of a sharp fire from three sides. . . .” Also losing heavy numbers in captives was the 45th Pennsylvania. Their history reports that the regiment “lost 8 officers and 170 enlisted men out of about 200.” A count of the 48th Pennsylvania enumerated 43 captured or missing soldiers.

Capt. Whitman’s 51st New York seems to have come out of the battle the worst for wear in terms of numbers captured. The Confederates captured 332 officers and men, almost the whole regiment. In effort to dispel the fears of his family, Whitman wrote home as soon as he could. In a letter to his mother dated October 2, and still located in Petersburg two days becoming a captive, Capt. Whitman explained his current situation: “Here I am perfectly well and unhurt, but a prisoner,” he wrote. To reassure his loved ones, he stated, “I am in tip top health and Spirits, and am tough as a mule and shall get along first rate, Mother please don’t worry and all will be right in time if you will not worry.” George requested that Walt or another brother write to Lt. Babcock, who apparently escaped capture, and “tell him to send my things home by express, as I should be sorry to lose them.”

Although Capt. Whitman’s letter does not specify, it was a common Confederate practice during the Petersburg Campaign to detail a regiment, or more, to guard and transport captured enemy soldiers from the battlefield to the rear and then on into Petersburg where they were kept. Sometimes temporarily held in old tobacco warehouses, and sometimes on Merchant’s Island in the Appomattox River, prisoners briefly waited before moving on to Richmond and Libby prison where Confederate authorities processed captured Union soldiers.

Capt. Whitman apparently wrote a letter from Libby prison that did not make it home. He wrote again from Danville, Virginia, on October 23, where he reiterated much of his October 2 Petersburg letter, reassuring his mother that he was well and to have Lt. Babcock send his personal possessions home. George sent another letter home from Danville on November 27. The Whitmans received the slow traveling letter in January 1865, but it appears to no longer exist. George’s trunk of personal possessions arrived the day after Christmas 1864. Walt wrote in his diary, “It stood some hours before we felt inclined to open it.” Walt then wrote beamingly to the Brooklyn Daily Union that his little brother was well and proudly included that George had been in “genuine fighting service in all parts of the war.”

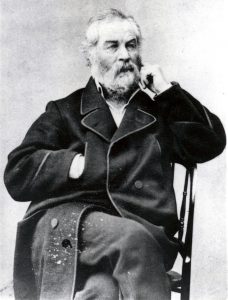

George Whitman arrived at Annapolis, Maryland, on February 23, 1865, for a prisoner exchange involving 500 officers. He soon received a 30-day furlough that he used to go to Brooklyn and visit with family that he had not seen in over three years. Due to poor health, George received an extension on his furlough, but he returned to his regiment in Alexandria, Virginia in May 1865. The 51st New York Infantry mustered out that July. Walt honored his little brother with a biographical sketch in the August 5, 1865, Brooklyn Daily Union.

A civilian again, George went back to work as a carpenter. He moved to Camden, New Jersey, and married in 1871. He then worked as an inspector of gas pipes in Camden. George and his wife Louisa took in mother Whitman until her death in 1873. Then when Walt suffered a stroke, he came to live with his younger brother’s family for 11 years. In 1884, George and Louisa moved to a country house George built in Burlington, New Jersey. Walt did not go with them. Apparently, the move fractured the brothers’ relationship. Walt died in 1892, and Louisa passed away about six months later. George died in 1901, and is buried Burlington.

Sources:

Albert, Allen D. ed. History of the Forty-Fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1865. Grit Publishing, 1912.

Committee of the Regiment. History of the Thirty-Sixth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, 1862-1865. Rockwell and Church, 1884.

Cushman, Frederick E. History of the 58th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers. Gibson Brothers Printers, 1865.

Bearss, Edwin C. with Bryce A. Suderow. The Petersburg Campaign: Vol. II, The Western Front Battles, September 1864-April 1865. Savas Beatie, 2014.

Hess, Earl J. In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications and Defeat. University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Hess, Earl J. Lee’s Tar Heels: The Pettigrew-Kirkland-MacRae Brigade. University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Loving, Jerome M. ed. Civil War Letters of George Washington Whitman. Duke University Press, 1977.

O.R. Vol. 42, Part 1

Sommers, Richard J. Richmond Redeemed: The Siege at Petersburg. Doubleday and Company, 1981.

Tim Talbott is the Chief Administrative Officer for the Central Virginia Battlefields Trust. He is the former Director of Education, Interpretation, Visitor Services, and Collections at Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier in Petersburg, Virginia. Tim is also the founding member and President of the Battle of New Market Heights Memorial and Education Association. He maintains the “Random Thoughts on History” blog and has published articles in both book and scholarly journal format. Tim’s current project is researching soldiers captured during the Petersburg Campaign.

1 Response to “Here I am . . . a Prisoner:” The Capture of Walt Whitman’s Brother