Colorado’s Confederate Hideout

In 1862, Confederate Brig. Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley invaded New Mexico with around3000 Texas cavalry and supporting artillery. Building on earlier Confederate success in organizing a secessionist Arizona Territory, Sibley sought to bring the remainder of the Southwest into the fold, open a path to the Pacific, and secure the recently discovered gold fields of Colorado.

Sibley was relying in part on support from Confederate sympathizers in the territory that he would be occupying. His artillery chief, Major T.T. Teel, wrote, “His campaign was to be self sustaining … Sibley was to utilize the results of Baylor’s successes, make Mesilla the base of operations, and with the enlistment of men from New Mexico, California, Arizona and Colorado form an army.”1

Sibley never reached Colorado; his army was turned back at the battle of Glorieta Pass in northern New Mexico. They were stopped, in large part, by Colorado volunteers who marched hundreds of miles to make it to the battle. But how much support could Sibley really have hoped to gain in Colorado?

At the outbreak of the war, the territory was only recently established. Most White settlement as of the Civil War had been prompted by the discovery of gold in the late 1850s, and the associated businesses that sprang up to support waves of prospectors. With a sparse population, slow communications and rumors running wild, Union commanders and the federal government were forced to speculate just how high the initial secessionist wave would crest.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that there was at least an undercurrent of support for the Confederacy. A Confederate flag was hoisted on Larimer Street in Denver, along with reports of sporadic confrontations in the city.2 Colonel R.S. Canby, commanding Union forces in New Mexico, wrote to his superiors St. Louis warning that, “The trains en route for this country are again threatened by marauding parties from Colorado Territory.” He voiced similar concerns to authorities in Washington, specifically worrying that Confederate sympathizers would attempt the “seizure of military posts or public property.”3

The territorial government of Colorado was also convinced that there was a significant risk. On October 25, 1861, Governor William Gilpin wrote that “The malignant secession element of this Territory has numbered 7,500. It has been ably and secretly organized from November last, and requires extreme and extraordinary measures to meet and control its onslaught.”4

7,500 Confederate supporters would have accounted for about a fifth of the territory’s population of 34,277, as of the 1860 census. Census takers also collected, and reported on, respondents’ native states. According to that data, only 8% of Coloradans originally hailed from a state that seceded, while another 16% called a border state home, mostly Missouri and Kentucky.5

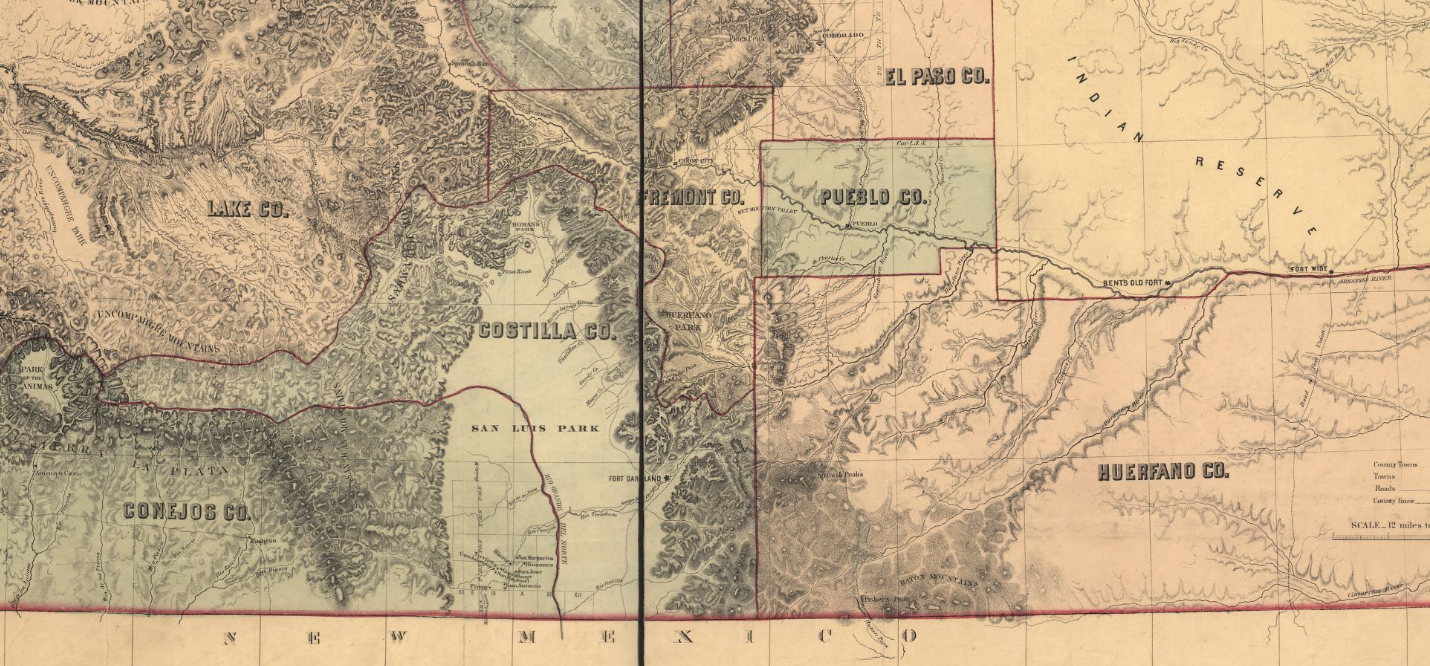

The largest reported concentration of Confederate support was in a small valley in southern Colorado called Mace’s Hole. Named for Juan Mace, an outlaw in the area in the 1850s and 1860s, the location had easy access to major thoroughfares, while also being tucked away and easily defended, made it a good hideout for both bandits and clandestine Confederates in Union territory.

Daniel Conner, a Kentuckian who ventured west to Colorado in search of gold and later sought to join up with Confederate forces, noted the great care that was taken to keep their recruitment operation off the radar of Union authorities:

“No new recruit was ever allowed to come directly to Mace’s Hole. They were recruited and sent to a small camp up above Pike’s Peak more than fifty miles from Mace’s Hole. This small camp was in charge of trusty men, some of whom would accompany the recruit to Mace’s Hole as their escort. By this means a traitor could not jeopardize the safety of any but the little recruiting squad.”6

Conner cites 600 Confederate troops in Mace’s Hole, a significant force when we consider the small numbers of troops involved in campaigns this far west. Sibley had 3000 troops at the beginning of his campaign At the battle of Glorieta, it’s likely that neither side fielded much over 1,000 men. Armed, trained, and well-led, 600 Confederates would have been difficult to pry out of this position, which Conner described in detail after the war:

“But from my best recollection, this hole was about half a mile or more in diameter and completely hedged in by a perpendicular wall, varying in height from ten feet near the ditchlike entrance around the circle, rising gradually higher as it neared the higher ascending mountain, where it was hundreds of feet in height, then gradually descended around the other half-circle to the mouth of the ditch or entry. This entry was a narrow lane between two walls also, until it opened on the plains. The ditch was like the ‘hole’ – bounded by perpendicular walls and possibly from twenty to fifty feet in width. Such was the place selected by Col. John Hefffiner in which to organize his Confederate regiment.”7

Having been there, I can confirm it’s a reasonably accurate description. It was an ideal location for mobilizing troops in unfriendly territory,easily kept out of sight, with ready access to water and provisions, and easily defensible at the entrance. What kind of impact might 600 organized, armed Confederate troops have had operating out of this area?

Conner notes that Mace’s Hole “was within a mile of the military road leading from Denver, Colorado to Fort Union, New Mexico.” Any organized force there would have been in a strong position to disrupt Federal communications, panic Union authorities in the territory, and potentially support Sibley.8

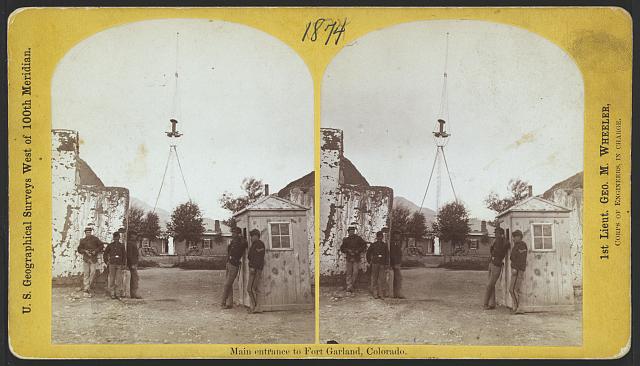

More intriguingly, Conner describes a detailed plot that was hatched to capture the lightly defended Fort Garland, near the border of New Mexico and Colorado. He paints a picture of a garrison of only 30 or 40 men, sympathetic to the Confederate cause, and sitting on hundreds of small arms that could be used to fully equip the regiment forming at Mace’s Hole.9

Conner was writing after the war, but at least in hindsight, the plan was reasonably well-crafted. It’s a little more optimistic than a report in the official records from around that time, which showed 137 men present for duty at the fort. But with 600 men, supporters inside the walls, and the element of surprise, it’s at least conceivable that the plan could have succeeded.10

There are plenty of red flags here to give us pause, though. I’ve often seen Conner’s account cited at face value, implying there were 600 Confederate troops actively under arms. It’s an intriguing possibility, but we should at least be skeptical of the idea that there was really a militarily significant force available here. They were clearly relying on arms captured from Fort Garland to army the regiment, and Conner’s description of the 600 men in the unit includes the important hedge that “really there was never this number in the hole at once, but this was the headquarters.” There’s a world of difference between 600 reported recruits who are never seen together in the same place, and an effective fighting force taking the field together at the same time.11

This is a familiar theme for anyone who’s studied other Confederate offensives in 1862. Those campaigns were also launched, in part, with the idea that supporters in Maryland and Kentucky would lead to an outpouring of recruits and supplies, but that proved to be wishful thinking.

Ultimately, the nascent Confederate force at Mace’s Hole was broken up by Union forces before it could have any impact on the war. Sibley abandoned New Mexico after this defeat at Glorieta, and for the remainder of the war, Colorado faced few Confederate threats. The occasional rumor surfaced of a Confederate raid from Texas, without ever coming to fruition. A handful of partisan raids by Confederate sympathizers would make the papers, but they straddled the gray area between irregular warfare and general crime.

Mace’s Hole was renamed Beulah in 1876, when Colorado became a state. Beulah is still there today, a little off the beaten path, but worth visiting if you find yourself in the area.

- Major T.T. Teel. “Sibley’s New Mexico Campaign – Its Objects and the Causes of its Failure,” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, 1888, 700.

- Smith, Duane A. The Birth of Colorado: A Civil War Perspective. University of Oklahoma Press. 1989. 12.

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), Series 1, vol. 4, pages 68, 74.

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), Series 1, vol. 4, page 73.

- Statistics of the United States Census (Including Mortality, Property, &c.) in 1860, Washington Government Printing Office, 1866, 549. To be precise, 8.47% of the population hailed from seceded states, 16.44% from border states, and 66.11% from solidly Union states. The remaining 8.99% were foreign-born, didn’t answer, or claimed other territories as home…and a single soul had no native state because they were born at sea. It’s worth noting that in 1861, the U.S. Marshal conducted a separate census that arrived at a significantly smaller population for the territory, but there’s some reason to be skeptical of that data.

- Conner, Daniel Ellis. A Confederate in the Colorado Gold Fields. University of Oklahoma Press. 1956. 138.

- Conner, 134.

- Conner, 134.

- Conner, 146-147.

- The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), Series 1, vol. 4, page 696.

- Conner, 133

Very interesting. You don’t get to hear very much about the ultimate western theater of the Civil War.

Nice piece. Thanks for posting.

Tom

For those interested in learning more, Three-Cornered War by Megan Kate Nelson is a fascinating history of the Civil War in the American West.

The Confederates constantly fantasized about support in the Southwest during the first year of the war. There was alienation with the U.S. government by the Mexican-born majority in New Mexico. The region had been violently taken by the U.S. only a little more than a decade earlier, but the white population of Texas was seen as even more alien. Texans had tried to take New Mexican land before and the 1862 invasion looked like another “filibuster.” New Mexican Latinos who fought in the Civil War did so almost entirely on the Union side.

I agree: the Confederates seem to have had a problem with math. “One Southron is worth ten Yankees” and “Thousands of supporters in California and the Territories will rally to our Cause” spring to mind. Even so, the ultimate aims of Confederate BGen Sibley deserve a closer look.

Excellent post. Given the mountainous and arid conditions (at least compared to the Eastern Theater), the logistics involved in supplying 600 men at Mace’s Hole seem incredible — if possible at all. Thank you for this post!