“I take my pen in hand:” An Unpublished Letter from a Pension File

As explored in an earlier post by Douglas Ullman, Jr., pension files can offer immense insight into the lives of soldiers. Sometimes, researchers are lucky enough to find wartime letters written by the soldiers in the file. In this case, my relative Peter Goodling Reever wrote this letter while in camp with the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry around Winchester, Virginia in the spring of 1863. A few months later he was captured at Carter’s Woods/The Second Battle of Winchester, taken to Richmond as a prisoner and eventually paroled. He returned to the regiment, was slightly wounded at Petersburg and captured for a second time at Monocacy. He was taken to the prison in Danville, Virginia, where he died. (See my earlier blog post for this story.) While some elements of his service were noted in other sources, the pension file (as well as his service record, also stored at the National Archives) filled in several gaps that I couldn’t find answers to elsewhere. Postwar, his mother filed this pension paperwork, though she was ultimately denied due to local affidavits that she and Peter’s father did not rely on financial support from their son at the time he was in the army. As far as I know, this is Peter’s only wartime letter that survived, and it only exists today because his mother sent included it in her pension paperwork. It was chosen not necessarily for any poignant text or important discussion of military actions, but because it notes that he sent money home to his parents.

As explored in an earlier post by Douglas Ullman, Jr., pension files can offer immense insight into the lives of soldiers. Sometimes, researchers are lucky enough to find wartime letters written by the soldiers in the file. In this case, my relative Peter Goodling Reever wrote this letter while in camp with the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry around Winchester, Virginia in the spring of 1863. A few months later he was captured at Carter’s Woods/The Second Battle of Winchester, taken to Richmond as a prisoner and eventually paroled. He returned to the regiment, was slightly wounded at Petersburg and captured for a second time at Monocacy. He was taken to the prison in Danville, Virginia, where he died. (See my earlier blog post for this story.) While some elements of his service were noted in other sources, the pension file (as well as his service record, also stored at the National Archives) filled in several gaps that I couldn’t find answers to elsewhere. Postwar, his mother filed this pension paperwork, though she was ultimately denied due to local affidavits that she and Peter’s father did not rely on financial support from their son at the time he was in the army. As far as I know, this is Peter’s only wartime letter that survived, and it only exists today because his mother sent included it in her pension paperwork. It was chosen not necessarily for any poignant text or important discussion of military actions, but because it notes that he sent money home to his parents.

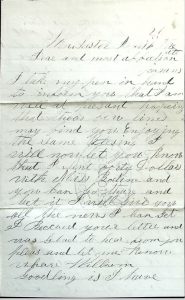

Below is the text of the letter, with original spelling as well as question marks where I wasn’t sure of the word.

Winchester April the 21

Dear and most affectionate parans

I take my pen in hand to inform you that I am well at presant hopeing that theas few lines may find you Enjoying the same Blesing I will now let you know that I sent forty Dollars with (Miss?) Bodin and you Can Go thare and Get it I will Give you All the news I can Get I Received your letter and Was Glad to hear from you Pleas and let me know Where William Goodling is I have

(page break)

wrote before this time in order to find out whare he is I have herd nothing of him Since I am in the (lines?) tell Him to write to me I think I will com Home this summer Some time But at present I Cannot Come thare is to many Going unless you have Some thing particlar that I shall Come home than write it to me and I can come soon or I think that we will Stay here this summer unless we will be cleaned out it is reported here that General (hooker?) is (fiting?) at Fredericksburg

(page break)

A few lines to my Brother Ulrich Dear Brother I will here drop A few lines to you Dear Brother if you Get Drafted put your trust in God and can comfort you he can help you Every thing of (???) thinks there as G is a God of battels and the Best thing is to prepare for the future times ho what a dreadful thing it is to be Caste away from the presans of God think of the Rich man he had his plesher in this world and he must have his punishment in the world to Come

(page break)

When you write again let me know all the news as I do not hear much from Pensylvania I like to Hear what the news is I must Bring my Letter to a Close for This time no more

But Remain your true and affectionate

friend Peter G Reever

write soon again

“Not reliant on their son’s financial contributions.” Just one of many lame excuses that the U.S. Government used to deny pension claims following the Civil War. As result, a whole Pensions Claim Industry sprung into being; and the National Tribune newspaper acted as its mouthpiece.

It’s complicated. By the accounts from neighbors, it really sounds like the Reevers (the parents) were fairly well off and ran a large farm during and after the war. They had basically no help from Peter, who had a bit of a reputation for unreliability and even left some debts when he joined the army that his father had to pay.

For more information on how the Civil War Pension System worked, see the attached brief article: https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/civil-war-pensions.html

This man was captured in the little known battle of Monocacy. I just happened to visit the beautifully preserved battlefield last Sunday (it’s right next to Frederick, MD), and would highly recommend it. It’s free, has a nice visitor center and electronic map, and has plenty of nice walking trails. It was particularly impressive because of the current riot of fall foliage colors. Check it out.

Yes! Monocacy is one of my favorite sites to visit (and was before I learned these stories). The park is well maintained, and I agree with all your notes on it. I linked to an earlier post I did on the regiment at Monocacy and the prisoner experience.

Now, the citation of pension files as a primary source poses a very interesting set of methodology questions to engage with.

The specific letter cited here is from while the war was being fought. There is no dispute about that in and of itself.

And of course, an enormous amount is contingent about the questions that are raised and what we claim the evidence presented ‘proves’ or can shed light upon.

But emphasis of the relative value of primary documents has emphasised that those closest to the start of the war are most valuable, those during the war are so so, but those written AFTER the war, specifically, Confederate materials, are deemed of no or very little value.

My research has shown that ALL evidence is to be read critically from any point it originates at, American or global. But no evidence can be tarbeushed as having no value at all.

But, if we accept the argument that evidence written after the war is of far lesser value than that at war’s start, or even during the conflict, suddenly, there is a large amount of questionability as to the value of pension files/documents written after the war, long removed from the contemporaneous nature of other documentation.

No one can question the pension applicant felt physical pain/had injuries; but if the methodological argument is sound that I cite above, we have to be sceptical in the very least about the information contained in these.

Thoughts?

The most important part of reading any source is to understand what the original person intended with their writing; what was the purpose/what were they trying to explain or convince someone on? It isn’t as simple as “3 years out is more ‘reliable’ than 10 years later.”

This is why reading a letter intended only for the eyes of a loved one or close confidant is different than reading a letter a soldier wrote home explicitly for publication in a local newspaper.

In this case, it’s important to understand the context of the pension application – the Reevers are choosing their words, testimony, and sources to make the argument that they relied on support from their son to meet the requirements of the pension laws. Everything makes some kind of argument, and pension applications are very obvious in what they’re trying to achieve.

Your mention of Confederate records is off topic from an article about a letter in a pension file, but the reason historians often lean the way you describe is important in the context of historical memory. If I’m interested in exploring why states seceded and how they justified it at the time, I’m much more likely to rely on the original Ordinances of Secession than something written by a former Confederate in the 1880s. If I’m interested in seeing how former Confederates justified it after defeat, then the post-war writings are important and “reliable” in that context.

I agree that understanding the audience, and situational context as applicable, either direct or in a more wide spread manner, is key.

There can be times when letters to loved ones are not necessarily as accurate as those written to a more public, or numerous, audience, (ie., Robert E. Lee wrote of punishments he thought appropriate for military misconduct to other military bodies that are not to be found in those to his family, such as recommending charges be brought against the Confederates responsible for the atrocities against USCT in the hospital at Saltville, Virginia, in 1864). It depends, again, on the questions put and the evidence engaged.

It may be obvious what pensioners are trying to achieve, as I had said, no one disputes what they were injured/in pain. This did not instantaneously render their accounts long after the historical event in question beyond reproach, especially when one considers that in the field of the CW/WBTS, sources that are presented after the conflict are not seen as wholly trustworthy.

My citing of Confederate sources was to highlight the point above s as bout dealing with primary evidence and methodology; accounts from the same parties whom fought the war, even long after, are still primary sources.

Frankly, while I can see some merit in your argument, nor can I agree with it wholly. The existence of a wide degree of evidence at the time of the war began by the Confederates which cite slavery, but also other factors, (federalism, etc, etc), and how these are cited with varying degrees of emphasis in the post-war too, renders your postulation open to challenge.

For example, your citing of the Ordinances does not explain Robert E. Lee’s emphasis on his view as states as his reason to fight, or John Mosby’s pointing to slavery in the post war. In other words, there is too much evidence in pre, inter and post-war citation to fully agree with you.

The same can be said for the Union, as Ulysses S. Grant’s statements in his Memoirs are incompatible with those he spoke with regards to slavery in Kentucky in 1861, prove.

The totality of evidence shows more than your argument would concede and it also challenges the methodology I’d put.

But, I appreciate your response. Thank you.

Actually, one other thing, Jon, the structural emphasis on varying evidence/themes/etc, between the start of the war and inter war, compared to it in posterity, reflects in my mind an obvious reality that neither side, or succeeding generations of Americans with loyalties to one or the other, of the conflict wanted to readily admit-

The aims/nature/goals/etc, of both combatant sides changed over the course of the war, especially with regards to the issue of slavery, from an interest in preserving/protecting it on both sides to each being willing to embrace emancipation as essential for victory, with varying degrees of altruism/pragmatism.

Very moving, especially his advice to Ulrich.