The Nashville Petition of 1865 and the Promise of Reconstruction: Part II

ECW welcomes back guest author Heath Anderson. See Part I here.

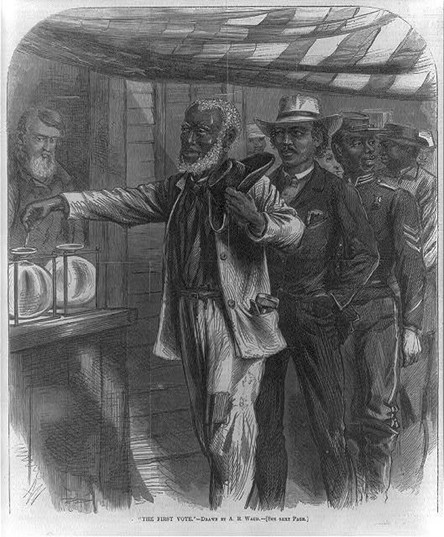

The idealism of the unidentified Nashville petitioners was codified in August of that same year during the first gathering of the “State Convention of Colored Men of the State of Tennessee,” from August 7 to August 10. While slavery had been abolished, the ideals expressed in the Nashville Petition in January regarding suffrage and full legal rights remained unfulfilled. In a committee of Black Reverends, USCT veterans, and other local leaders, likely many of the same men who had signed the original petition, this convention reaffirmed the Nashville petitioners’ rhetoric on the American founding. The recorder of the convention’s proceedings described how Sergeant H.J. Maxwell, a veteran of a USCT artillery battery, opened the convention with “an eloquent speech, in which he struck the keynote of the occasion. He was there as an American, claiming the inalienable rights of a man. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were his prerogatives.” During this four-day convention, these Black Tennesseans nominated a state committee and set up rules and regulations for advocating for their political and legal rights. Commenting on what they hoped to gain through this process, the convention’s recorder restated the argument that Black people’s military service and loyalty to the Union made them worthy of citizenship and suffrage. He stated that, “we want two more boxes, beside the cartridge box—the ballot-box and the jury box. We shall gain them. The government of this nation will not prove false to its plighted faith. It proclaimed freedom, and we shall have that in fact.”[1]

Building off the January petition, the State Convention in August is instructive for demonstrating how the appeals of African Americans to their sacrifice for their country and their faith in the natural rights of all men made an impact on white Republicans. In a speech at the convention, a Black Reverend, James Lynch, put it simply: “We are part and parcel of the American Republic…we simply ask for those inalienable rights which are declared inalienable. Why should we not have them?” One prominent white attendee of the convention agreed. Brigadier General Clinton Bowen Fisk, the Freedmen’s Bureau commissioner of Tennessee and several other states, rose to address the convention. After acknowledging the momentous changes wrought by emancipation, Fisk told the delegates that “I come before you as your friend” and stated his belief that the government had a duty to aid the freedmen for the good of both races. Turning to the unfulfilled issue of suffrage that Black attendees were pressing for, Fisk succinctly expressed the unity of purpose and ideology that many white Republicans shared with freedpeople in their determination to exercise their rights as American citizens. “The passing of slavery has opened a new era,” Fisk began, “I was one of the first men to give the colored man a bible—the first to give him a bayonet—and I shall not be behind in giving him the ballot. With this swarm of B’s I think the negro will take care of himself.” After further promises to include Black people in discussions about how to make the Freedmen’s Bureau work for them in Tennessee, Fisk concluded his remarks. From the original petition in January, to the convention in August, Black Tennesseans made remarkable progress in organizing their Republican allies behind their cause. By linking their appeal for rights to the broader process of restoring a stable Union, they established a formidable political coalition with white Republicans to reconstruct the South.[2]

The Nashville Petition, and the subsequent convention of African Americans that August, are just two examples of the concerted grassroots effort by freedpeople across the former Confederacy to advocate for their rights as the Civil War ended. One historian of Black politics describes this movement as “widespread mobilizations of freedpeople across the former Confederate South.” Like the Nashville Petition, the Black people at these gatherings asserted their loyalty to the United States and pressed Republicans for suffrage and full citizenship. In May 1865, a group of Black people from North Carolina wrote to President Andrew Johnson, lauding the restored Union and stating that “we always loved the old flag, and we have stood by it…now that it has brought us liberty, we love it more than ever, and in all future time we and our sons will be ready to defend it by our blood.” Another petition from the “Colored people of Mobile” in August of 1865 to the local military commander mirrored the Nashville petitioners’ connection of natural rights with the nation’s founding documents when it stated, “next to our heavenly Father we revere the good old Constitution of the United States…and we are unanimous as a people to die in its defence.” This burgeoning movement by Black people at the ground level reinforced Republicans who wanted to pass legislation to secure liberty for the freedpeople and prevent former slaveowners from regaining political power. These measures were the Civil Rights Bill and the Fourteenth Amendment.[3]

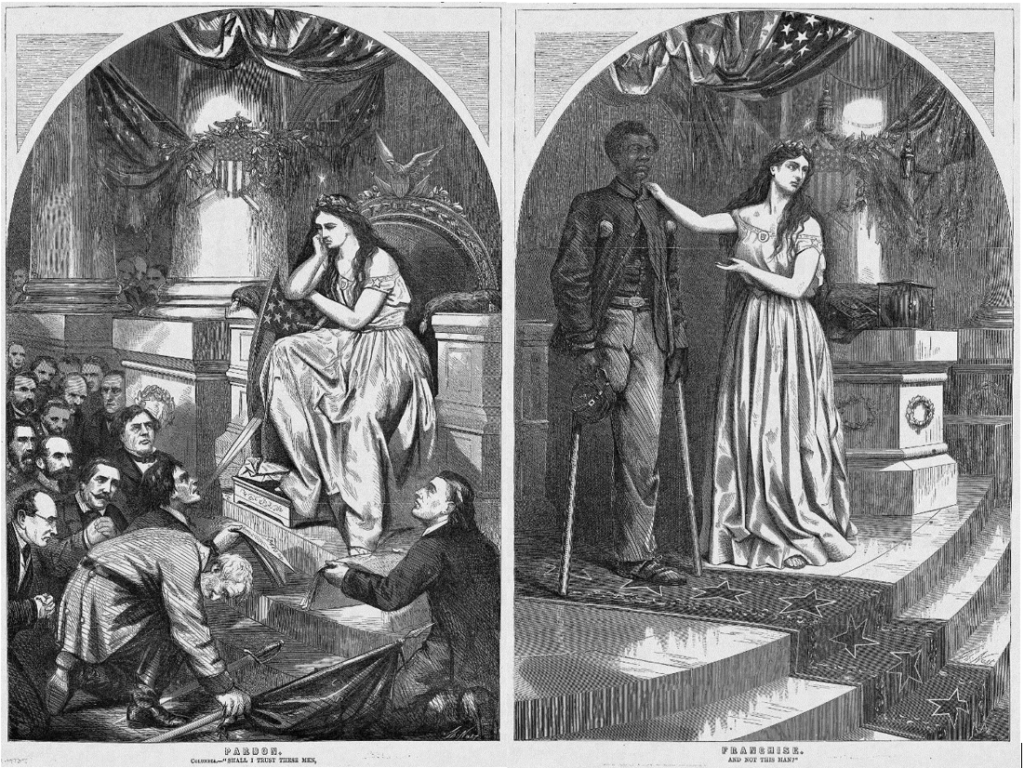

Passed in April and June of 1866 respectively, the Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment embodied the sentiments expressed by the Nashville petitioners and others like them and represented a unity of purpose among these Black advocates and the Republican Party and a shared belief in America’s founding principles of liberty and equality. By recognizing Black suffrage, Republicans eliminated the race-based distinctions between citizens that existed under slavery and established a coalition of loyal citizens in the South. For Republicans and Black people, this eliminated the contradiction of slavery’s legacy in a free republic once and for all. As Frederick Douglass stated, this would make the government “consistent with itself, and render the rights of the states compatible with the sacred rights of human nature.” All of these accomplishments came just a few years after the end of the Civil War and vindicated the Nashville petitioners’ fervent belief that Union victory was a historical achievement that would only be complete with their enfranchisement and equality before the law as American citizens. Having passed from slavery to citizenship in the span of a few years, the central ideals of the Black residents of Nashville in 1865 were realized.[4]

While Black voting secured by the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Reconstruction Acts is generally lauded as a radical achievement, the collapse of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow make it tempting to discount emancipation and Reconstruction as abortive attempts to impart real, lasting justice. This is an argument with which the freedpeople who wrote the Nashville petition might well have disagreed. In powerful language predicated on a firm belief in natural rights and a religious faith, the Nashville petitioners viewed the end of the war as a triumphant verdict in favor of the principles of freedom and equality. “We hold that freedom is the natural right of all men, which they themselves have no more right to give or barter away, than they have to sell their honor, their wives, or their children,” they wrote. They continued by linking this philosophy of freedom and natural rights to the biblical teaching that “god no where in his revealed word, makes an invidious and degrading distinction against his children, because of their color. And happy is that nation which makes the Bible its rule of action, and obeys principle, not prejudice.” In this argument, these freedpeople, together with their Republican allies, viewed freedom as humanity’s natural condition. This condition had been sadistically inverted by proslavery advocates who argued that the Declaration’s proposition of equality had gotten it wrong, and that the Confederacy was a new nation, founded on the “truth” that “the negro is not equal to the white man,” to use Alexander Stephens’ infamous language. For these petitioners, emancipation was the repudiation of generations of proslavery rhetoric. It was the vindication of a moral right over a moral wrong, perhaps the most striking example of its kind in human history, with profound meaning for the future of the nation.

From the rupture of civil war, Black and white people looked into the future and reimagined what their nation might look like on the other side of the slaveholders’ rebellion. For many African Americans, this was a moment of hope that the nation would be made consistent with its founding documents, where liberty and equality before the law for all American citizens would be protected. As the Civil Rights Bill and Fourteenth Amendment demonstrate, the petitioners shared with many white Republicans an affection for a Union that could make this possible, creating, for a time, an alliance that reestablished the principle of equality as the cornerstone of the reunited nation. As the Nashville petitioners expressed in January of 1865, “In this great and fearful struggle of the nation with a wicked rebellion, we are anxious to perform the full measure of our duty both as citizens and soldiers…Our souls burn with love for the great government of freedom and equal rights.” For all the chaos and violence of history, the hopeful moments, and the seemingly inevitable failures, the Reconstruction era was a bold attempt to live up to the highest ideals of the nation’s founding. The words of the Nashville petitioners remind us that this is what freedpeople thought had been won during the Civil War and what they worked assiduously to uphold during Reconstruction. For the Black residents of Nashville, the chaos of war truly occasioned a new birth of freedom. Their advocacy for that freedom allowed for the highest principles of America’s founding to be reasserted and enshrined in the Constitution for all time.[5]

Heath Anderson is a Ph.D. candidate at Mississippi State University under the direction of Dr. Andrew Lang. He grew up in Virginia and developed a passion for history and the American Civil War from a young age, traveling to numerous museums, battlefields, and living history events. Heath attained his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Virginia Commonwealth University where he wrote a thesis on Confederate General William Mahone and the Readjuster Party. Heath’s primary research interest is the period of Reconstruction following the war, and how local politics and events influenced federal policy on Reconstruction.

[1] Daniel Wadkins, Nelson Walker, and Ransom Harris, Proceedings of the State Convention of Colored Men of the State of Tennessee: With the Addresses of the Convention to the White Loyal Citizens of Tennessee, and the Colored Citizens of Tennessee (Nashville: The Daily Press and Times Job Office, 1865), 6. Web Link: https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/files/original/ebbb1a5b7b7c4893be155312338cb820.pdf

[2] Ibid., Quotes from James Lynch on 6-7, Quotes from Fisk on 12 and 15.

[3] Steven Hahn, A Nation Under our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), 2; Colored Men of North Carolina to Andrew Johnson, May 10, 1865, quoted in Brooks D. Simpson, Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality (New York: Library of America, 2018), 24; Colored People of Mobile to Andrew J. Smith, August 1865,quoted in Simpson, Reconstruction, 71.

[4] Frederick Douglass: Reconstruction, December 1866, quoted in Simpson, Reconstruction, 295.

[5] “Black Residents of Nashville to the Union Convention.”

This new format really amplifies the importance of the inclusion of illustrations with the blogs. The top drawing is amazing!

The Waud “ First Vote” illustration and the clear writing on display in Part 2 helps to complete a compelling story. Thanks