Haunted by Death: Garrison Duty at Key West, Florida

ECW welcomes guest author Dr. Angela Zombek

“I want to come [home] with the regiment if I can but I shant stay and die here if I can help it,” John Olivett of the 90th New York Volunteers wrote to his sister on July 15, 1862 while on garrison duty at Key West, Florida. Olivett was torn between service and survival. He had recently recovered from a serious illness and the experience was enough for him to want out of the army. Olivett vowed to attempt to get discharged, as did a friend, but the belief that the war would soon end assuaged his fears, albeit temporarily. Yellow fever struck Key West in July 1862, and on August 11, Olivett somberly noted that his company buried a man, the first that they had lost. Olivett nervously hoped this would be the last since only one man in his company remained sick but was rapidly improving. In October, Olivett himself had a brush with death: He was stricken with yellow fever and typhoid for two weeks. The doctor thought Olivett “would not live from one minute to another,” but he survived.[1]

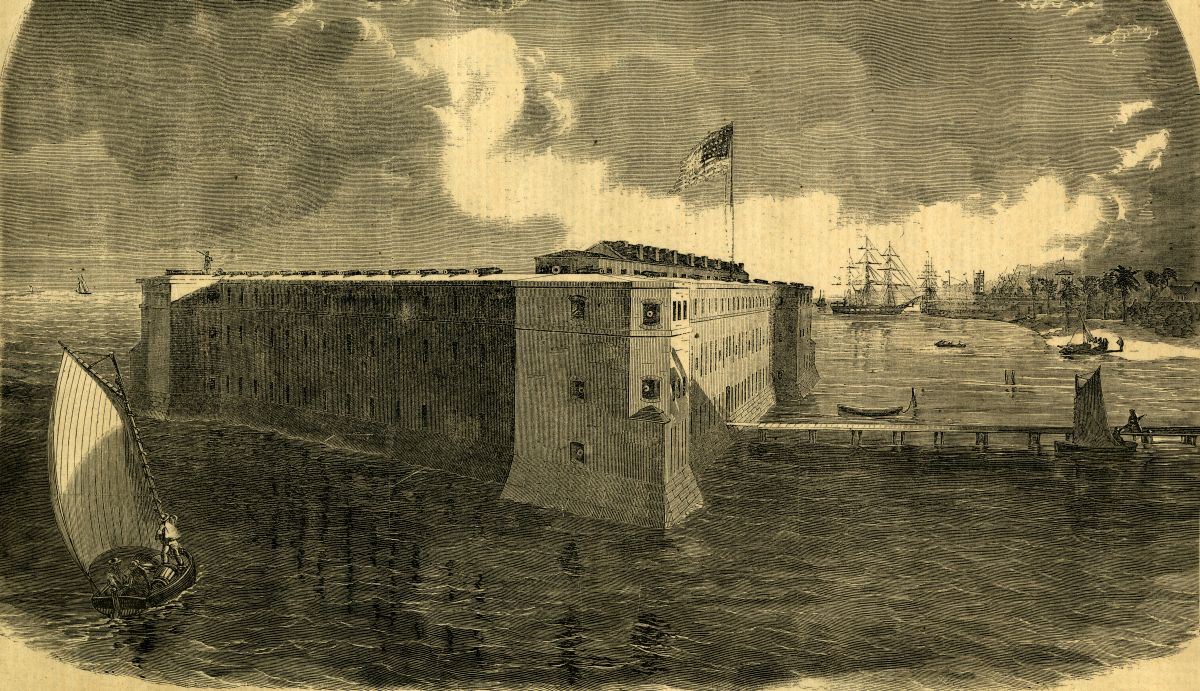

Olivett’s close encounters with and fears of death raises the questions of how soldiers who occupied Key West, the U.S.’s southernmost possession and a strategic military and economic point, made sense of death while on garrison duty and how they gave meaning to the sacrifice of lives absent combat. Key West’s significance could not be understated: It housed a Customs House that generated federal revenue, a U.S. District Court that decided lucrative salvage cases, and guarded the Florida Straits, a major shipping channel on which domestic and international commerce depended. Captain John Brannan of the 1st U.S. Artillery secured Fort Taylor and Key West for the U.S. on January 13, 1861, shortly after news of Florida’s secession on January 10 reached the island. The 90th New York, 91st New York, and 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were assigned to reinforce the regular garrison and occupy Key West without having any combat experience. Their first experiences with death came in 1862 while garrisoning this tropical island that was far removed from any active theater of war, other than serving as the headquarters of the East Gulf Blockading Squadron.[2] These volunteers’ first reactions to death mirrored those of soldiers engaged in combat. Death elicited powerful, conflicting emotions from these troops, especially since soldiers feared dying of disease more than in battle.[3] Disease was one of the biggest foes that the garrison faced at Key West and death was one of the greatest challenges that they confronted.

The New York and Pennsylvania volunteers arrived at Key West in January and February of 1862 and initially had good fortune. As of March 14, 1862, the 91st New York had not lost any soldiers, but Captain John McDermott wrote that one man in Co. I would soon die. Death then seemed prevalent. That same day, McDermott noted that a detail from the 91st had organized to bury a convalescent soldier from Fort Pickens who died of dysentery the previous day. The victim was discharged and on his way home, where he likely would have had a good death surrounded by family, “but fearing he would die on the way he was left here in the hospital where he died.”[4]

On April 6 and May 31, 1862, Sergeant Henry Crydenwise of the 90th New York tried to allay his parents’ fears of losing him to disease. Crydenwise understood that his words would influence his parents’ perception of his well-being and knew that expressions of happiness indicated health, so he emphasized that his health and spirits were “uncommonly good” and the soldiers quite healthy, despite many who were sick and dying. “There is scarcely a day but what some soldiers from one of the three regiments here is born to the silent tomb,” he mournfully wrote, recalling the deaths of one soldier from the 90th New York and of a lieutenant from the 47th Pennsylvania. Crydenwise opined “we know not whose turn it will be next yet it matters little if we have not mistaken the real affect of life.” Crydenwise reflected the widely shared distress over soldiers dying miles from home when he informed his parents that his comrades would soon “deposit one of our companions in the silent grave. Here in this far off land of strangers.”[5]

The 47th Pennsylvania memorialized soldiers who died in April 1862 and praised their performance on occupation duty, imbuing their service on garrison with meaning. When William Robinson of Co. D died, Captain H.D. Woodruff hailed him as “excellent and attentive soldier” while fearing that even more men would die. Four soldiers from Co. D were sick in the hospital along with 71 other members of the garrison. On April 5, as a tribute to Robinson and an indication that soldiers who would die at Key West would not do so in vain, Co. D penned a resolution. It decreed that “It has pleased an All-wise Providence” to take Robinson home, proclaimed that, in death, the regiment “lost an efficient soldier, a true patriot, and a warm-hearted friend,” and offered sympathy to his family and friends. The men vowed to send the resolutions to his family and to local newspapers for publication.[6]

Crydenwise was likely aware of these resolutions, however he had a hard time comprehending tragic deaths. Soldiers feared anonymous death on the battlefield, but this was also possible on garrison. The Union Army did not track how many soldiers became victims by their own hand, yet Crydenwise chronicled an orderly sergeant killed while on a hunting party when another soldier’s gun accidentally discharged. The bullet passed through the sergeant’s head, killing him instantly. “How true that ‘In the midst of life we are in death,’” Crydenwise mused. A few weeks later, Crydenwise recounted another tragic death. Many thought that one soldier from the 90th had deserted, but the man’s body was found, putrefied from having laid in the sun, not far from camp. “It is sad to think of death under such circumstances,” Crydenwise cringed, exemplifying soldiers’ fear of anonymous death.[7]

When the yellow fever epidemic began in late July 1862, the prospect of death became even more terrifying, but John Lanigan of the 90th New York had feared death even absent disease. “I hope I will not die until we are once more united in love and harmony which is my daily prayer,” he wrote to his wife Ellen on April 11, 1862. Lanigan’s wish was unfulfilled. He died of yellow fever on September 9, 1862. Absent a system for reporting casualties, deceased soldiers’ close friends wrote sympathetic letters to family members and recounted the dying moments of their beloved men. Lanigan’s comrade, John Keeleher thus tried to assure Lanigan’s wife Ellen that he passed peacefully, courageously, and without complaint in the hospital. Keeleher described how Lanigan “died very easy without any pain but very chilled after three days sickness.” Honoring Lanigan’s sacrifice, Keeleher noted that Lanigan was “much regretted by all the men” despite death freeing him from suffering.[8]

Crydenwise’s best friend, Sergeant William Roe, also succumbed to disease. Roe died of yellow fever on August 23, 1862. His death made Crydenwise question, as did soldiers who were spared from death in combat, why they survived while others perished.[9] As the epidemic intensified, Crydenwise observed that some men feared they would contract the fever and he tried his best “by God’s grace to be prepared for the worst.” Roe was stricken on August 17 and Crydenwise was crushed after he passed. He didn’t think he could get by without Roe. Crydenwise trusted God but struggled to understand why he survived. As he ensured that Roe’s belongings and those of the regiment’s orderly made it home and informed families of their deaths, Crydenwise wondered, “Why am I spared when so many promising ones have fallen God only knows.”[10]

Crydenwise expressed similar feelings after recovering from yellow fever. On September 23, 1862, he reported that ten to twenty-three men had died from each company and acknowledged that it was “very hard to bury a comrade and friend in this far off strange land” despite assertions that Key West felt like home. Crydenwise fatalistically pondered why he was spared while so many perished. He was resigned to his fate, should he die, but believed that Roe was better off in the afterlife. Crydenwise’s faith ensured him that “God doth all things well” and, though he missed Roe, Crydenwise asserted that he “would not call him back for it is well with him,” a confession inspired by his religiosity, the lens through which many soldiers made sense of death.[11]

Exactly one week before Roe’s death, Capt. John Sullivan of the 90th New York died of yellow fever. Published tributes, intended to imbue soldiers’ deaths with meaning for audiences both on island and on the home front, extolled Sullivan’s character as a soldier, highlighted the importance of occupation duty, and recounted the admiration he earned from his men. They also gave meaning to garrison duty. On August 26, 1862, the Brooklyn Eagle recalled that “when the tocsin of war sounded” Sullivan was “the first to respond to the call of his country.” Sullivan, a faithful soldier, commanded a regiment that “has not thus far participated in any battle,” but “does excellent service in garrison duty at Key West and on the Tortugas.” The Eagle mourned that disease was “more fatal to our troops in the South than the bullets of the enemy.”[12]

Sullivan’s Catholic funeral and burial at Key West reflected his personal sacrifice, commemorated the regiment’s loss, and reaffirmed the larger purpose of soldiers’ own existence. After the High Mass, the Key West New Era reported that a band played a dirge while his coffin “wrapped in the American flag,” was carried to the grave by four soldiers of his company, followed by St. Mary Star of the Sea’s priests and acolytes, regimental chaplain Bass, the 90th’s officers, friends and citizens, and a detachment of 100 men with reversed arms commanded by Captain George Bissell. After one priest performed “Catholic ceremonies,” Chaplain Bass followed with a prayer, “the Amen to which showed how deeply they felt the loss of one whom they loved, honored, and obeyed.” It also indicated soldiers’ hope that, if they died, others would similarly, though perhaps less elaborately, honor them. Officers received privileged treatment, as Sullivan’s funeral illustrates, and ceremonies continued in his native state. The Common Council in New York appropriated money to bring Sullivan’s remains home to Brooklyn on Feb. 17, 1864. A second funeral was held at the Church of the Assumption after which his body lied in state at city hall for a day prior to being taken to the final resting place at the Cemetery of the Holy Cross in Flatbush, N.Y.[13]

In 1898, when the Spanish-American War necessitated that U.S. volunteer and regular soldiers again travel to tropical islands, a story that commemorated the 47th Pennsylvania’s Civil War service at Key West appeared in the Allentown, Pennsylvania Chronicle and News. It described a relic from Camp Brannan, the name for Key West’s Union encampment when Gen. John Brannan was in command, that Mrs. A.N. Ulrich, niece of Lieutenant George Fuller (Co. F), possessed. The relic’s imagery reflected how occupation soldiers saw themselves during the war and wanted to be remembered. The frame, holding a photo of Fuller, had the words “Camp Brannan, Key West, Florida April 1862” inscribed on the back. Two carved soldiers holding muskets with fixed bayonets, symbolically defending two crossed flags and an eagle at the bottom of the frame surrounded Fuller’s image. During the war, garrison troops defended Key West, but many suffered inglorious deaths, as did Fuller, who died of stomach cancer during the war. The fact that Allentown’s local Grand Army of the Republic post was named after Fuller, who spent the majority of his service at Key West, indicates that even though occupation did not fit the heroic track of soldiers’ experiences, he and his comrades who sacrificed their lives garrisoning the island deserved remembrance.[14]

Angela Zombek is Associate Professor of History at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. She is the author of Penitentiaries, Punishment, and Military Prisons: Familiar Responses to an Extraordinary Crisis During the American Civil War(Kent State University Press, 2018) and is Managing Editor of Kent State University Press’s “Interpreting the Civil War: Texts and Contexts” Series. Her current book project, Stronghold of the Union: Key West Under Martial Law, is under contract with the University Press of Florida.

[1] John Olivett to Sister, July 15, 1862; Aug. 11, 1862; and Oct. 2, 1862, John M. Olivett Papers, Rubenstein Library, Duke University. Olivett belonged to Co. H.

[2] “Battle Unit Details: 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Infantry,” https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UPA0047RI. The 47th was on picket duty outside of Washington in October 1861. “About the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers,”: https://47thpennsylvaniavolunteers.com/about/. “Battle Unit Details: 90th Regiment, New York Infantry,” https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UNY0090RI. “Battle Unit Details: 91st Regiment, New York Infantry,” https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UNY0091RI.

[3] Earl J. Hess, The Union Soldier in Battle: Enduring the Ordeal of Combat (University Press of Kansas, 1997), 6. Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (Knopf, 2008), 4.

[4] McDermott to Isabella, March 14, 1862, John Grey McDermott Civil War Letters, 1860-1865. Wisconsin Historical Society (hereafter McDermott Letters). The Good Death was central to mid-nineteenth-century Americans. Faust, Republic of Suffering, 6-10.

[5] Crydenwise to Parents, April 6, 1862 and May 31, 1862, Henry M. Crydenwise Letters, 1861-1866. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University Special Collections; (hereafter Crydenwise Letters). Peter S. Carmichael, The War for the Common Soldier: How Men Thought, Fought, and Survived in Civil War Armies (University of North Carolina Press, 2018), Chs., 2 and 3, Kindle Edition. Faust, Republic of Suffering, 9.

[6] “Tribute of Respect,” Perry County Democrat, April 24, 1862, p. 3.

[7] Gerald F. Linderman, Embattled Courage: The Experience of Combat in the American Civil War (Free Press, 1987), 248. Hess, Union Soldier, 50. Crydenwise to parents, June 9, 1862 and June 25, 1862, Crydenwise Letters.

[8] John Lanigan to Ellen, April 11, 1862; John Keeleher to Mrs. Lanigan, Oct. 25, 1862, Letters and Papers of John Lanigan 1862, Monroe County Public Library (hereafter MCPL). Linderman, Embattled Courage, 30. Faust, Republic of Suffering, 14.

[9] James M. McPherson, For Cause & Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (Oxford University Press, 1997), 44; Hess, Union Soldier, 29.

[10] Crydenwise to Parents, Aug. 19, 1862 and Aug. 26, 1862, Crydenwise Letters.

[11] Crydenwise to Parents, Sept. 23, 1862 and Sept. 28, 1862, Crydenwise Letters. For fatalism’s positive and negative overtones, see McPherson, Cause and Comrades, 64 and Ch. 5 generally. Faust, Republic of Suffering, 174.

[12] “DEATH OF CAPTAIN JOHN SULLIVAN,” Brooklyn Eagle, Aug. 26, 1862, p. 3. Faust, Republic of Suffering, 163.

[13] “LATEST NEWS FROM KEY WEST,” Key West New Era in Brooklyn Eagle, Sept. 11, 1862, p. 2. St. Mary Star of the Sea was dedicated on Feb. 26, 1852. Jefferson B. Browne, Key West: The Old and the New. A Facsimile Reproduction of the 1912 Edition with Introduction and Index by Ashby Hammond (University Press of Florida, 1973), 34. Faust, Republic of Suffering, 79. “THE LATE CAPTAIN JOHN SULLIVAN” Brooklyn Eagle, Feb. 18, 1864, p. 3: “Funeral Obsequies of the Gallant Dead,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 19, 1864, p. 2.

[14] “RELIEF FOR SOLDIERS’ FAMILIES,” Allentown, PA Chronicle and News, June 2, 1898, Camp Brannan Relic, MCPL. Information on Fuller from “47th Pennsylvania Infantry Roster”:http://ranger95.com/civil_war_us/penna/infantry/47pav/47th_rgt_inf.html. The 16th Connecticut’s “wartime service did not follow the standard and expected heroic trajectory,” so they “were largely ignored.” Lesley J. Gordon, A Broken Regiment: The 16th Connecticut’s Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2014), 228. Brannan was promoted to Brigadier General in December 1861.

Very well written story of a theater of the war that is so often overlooked. I’m looking forward to when this book will be published because I’m excited to see new information comes to light about underserved topics related to the Civil War.

Thank you! The book will likely be out in 2024 – I’m finishing it up this year!

Angie, Great article!

I am researching the life of Col. Stark Fellows, commander of the 2d US Colored Inf…stationed at Key West Feb-July ’64.

He is from my town of Sandown, NH. I am memorializing him before my town this coming May 29th 2023.

He was a well educated graduate of Thetford Academy and Dartmouth College.

His remarkable family gravesite is here in the town center.

Col Fellows died May 23 ’64 of yellow fever.

Can you shed any more light on his death or how yellow fever affected his African American troops vs the white officers.

How was he treated specically?

Were any conclusions drawn on who tended to live and who died of yf?

Looking forward to your book.

Send me an email and perhaps we can compare notes by phone.

Lieut. Col., I would be happy to – feel free to reach out to me at zombeka@uncw.edu.

A total of eleven officers of the Second United States Colored Infantry died of yellow fever that year. I’m working on a draft history of the Second, which has a full chapter on the outbreak. Here’s an excerpt, which underscores the degree to which the enlisted personnel, large numbers of whom came from regions where the fever was endemic, died at a much lower rate than the officers:

“…But by then the fever had already arrived and was playing freely among the garrison. The first fatality was Chaplain Schneider himself, who took ill on the evening of April 21, 1864 after the court had adjourned in the first day of the trial of the murderer Darius Stokes. The chaplain had gone from the court to deliver what he did not know was his last sermon at the funeral of Robert Williams of Company B, a 20 year old farmer from Princess Anne who had died earlier that day of typhoid. Schneider held on for several days before succumbing on Tuesday the 26th.

“…. At 3 a.m. on May 23, scarcely two weeks after returning from the raid on Tampa and three weeks after his 24th birthday, Colonel Stark Fellows himself died of the fever ….

“The disease evidently broke out in Fort Taylor and hit the four companies garrisoned there hardest: B, C, E, and F. On the first of May 55 men were ill; the number of sick in the garrison peaked at 77 on May 12 and plateaued in the upper 60’s for several days before falling. Company C was ordered to relocate to the Light House Barracks on May 16 and Company B on the 25th. As a result by mid-June sick rates declined to just two in each company. With the additional space the number of sick in the two companies remaining in the fort, E and F, dropped from 41 to four.

“Altogether nineteen enlisted men died out of a total of more than 600 in seven companies present in Key West in April and, after the deployment of Companies E and H to the coast, about 450 in five companies by the end of June. Overall the enlisted death rate came to somewhat less than 4%. As Commissary Sergeant Taylor noted to the Anglo-African in his report on the expedition to Tampa, “The health of the Regiment is not so good at present as it has been, and many of our men have already died from miscellaneous diseases.” It was bad, but very little compared to what happened to the officers.

“On May 28, hardly a month after Schneider’s death, the Chaplain was followed by his close friend Reinhardt, who had been promoted to Captain of Company A just ten days earlier. On the day after Reinhardt’s death Lieutenant Luther Z. Linton of Company F fell to the virus. Two days after Linton died, and just ten days after landing at Key West, Lieutenant Henry Meacham of Company E passed away, probably not yet having met any of the men in his command. On June 10 Lieutenant J. V. Coughnet of Company C fell to the fever, followed by Lieutenant Henry Kuhl of Company K, whom death mustered out on June 17, four months after he had mustered in. And on June 18, Captain Jared W. Martin of Company F, the diligent former tinsmith who had written optimistically about his health to his mother in April, also joined the ranks of the dead.

“More would come, though at increasing intervals. Lieutenant William Jackson of Company A, who had joined the regiment at Ship Island on January 16, left it on July 18. Two officers caught the disease but managed to linger until September before falling — Captain A. S. Springsteen of Company K on September 6, and Lieutenant A. P. Carpenter of Company K on the eighteenth. Carpenter had joined the regiment at Camp Casey nearly a year earlier as one of the regiment’s officers with serious combat experience. He came from the 1st Minnesota, which at Gettysburg made a legendary charge against a much larger rebel force in order to buy time for reinforcements to deploy behind it. They lost two-thirds of their men in the unequal contest and for Carpenter applying for a commission in the USCT might have seemed a way not to go through anything like that again. He became ill on May 10; with the same doggedness that saw his old regiment through that struggle at Gettysburg he managed to hold out four months, but no longer.

“Before the epidemic ran its course half the officers of the Second in Key West died of it. Companies C and E each lost a lieutenant, Company F lost its captain and a lieutenant, and Companies A and K lost all their officers. Nor was the attrition among the officers confined to deaths. Lieutenant E. P. Adams, the regimental quartermaster, traveled on duty to New Orleans April 19, fell sick there, recovered and obtained a transfer to the Signal Corps, never again returning to the Second or Key West. The 1st Assistant Surgeon, Alonzo Boothby, took sick on April 20, 1864 and received a discharge on June 9. Surgeon William McCully became ill and went home on leave in July; he would not return for several months. On June 21 General Woodbury mentioned to Admiral Bailey that there was “much sickness on the Key,” noting that not just McCully but Stocker was ill and he could not get along without Assistant Surgeon Parcell of the navy, then on duty at the Lazaretto.”

Thank you, Dr. Zombek, for citing “47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story” (https://47thpennsylvaniavolunteers.com) in your article. I’ve been researching this regiment’s history for well over a decade and launched a website in 2014 because the regiment had largely been overlooked by mainstream historians for more than a century. My goals since 2014 have been to preserve the 47th Pennsylvania’s history, to raise the regiment’s profile by raising the public’s awareness of its members’ accomplishments by creating biographical sketches for its individual members, and to make the documents associated with the regiment and its members (pre-war birth and census records, military paperwork such as enlistment papers, company rosters, soldiers’ medical and death records, and post-war records such as census rolls, death certificates and burial records) freely available to history professors and other professional historians, archivists, K-12 educators, Civil War enthusiasts, genealogists, and the general public.

With more than 2,000 men listed on the 47th’s rosters between 1861 and 1865, the project has been a daunting one. So, it’s particularly gratifying to see my work being read and cited. I just wanted to reach out to express my appreciation.

Kind Regards,

Laurie Snyder

Thank you for your kind words, Laurie. Likewise, I appreciate all of the work that you’re doing!