From Camp Servants to Soldiers – Part I

On July 9, 1861, Lt. Col. Barham Bobo Foster, 3rd South Carolina Infantry, wrote to his daughter in Spartanburg District from Fairfax Court House, Virginia, about how good army life was: “If you all knew how we enjoyed ourselves here you would not be uneasy about us. we live rough but have plenty of it . . . we have mutton chickens molasses & coffee.” Part of the reason Foster found camp so enjoyable was he had an enslaved cook named Mid doing much of the drudge work that soldiers, both North and South, would soon be complaining about in their letters home. Cooking, cleaning, laundering, and even foraging were just some of the burdensome duties that fell to camp servants.

About a month later, Foster wrote home again about Mid, but this time to his wife. Describing the Battle of First Manassas, Foster explained that during the fight he sent Mid to the baggage wagons and that Mid “was not alarmed he has had thousands of chances to be free but choses to stay with us. he does all of our cooking and does it well washes everything but our shirts and sometimes washes them, and irons them I have no fault to find of him,” Foster wrote.

Lt. Col. Foster’s previous confidence in Mid’s disregard for freedom proved misplaced. On September 4, 1861, Foster wrote his wife that, “I am sorry to inform you that Mid has at last chosen the cloven foot [the Devil]. Last night he left for parts unknown. Took his clothing I think it altogether likely that he is in yankeedom.” Foster seemed dumbfounded as to why Mid would leave. “nothing had occurred I had not even scolded at him,” Foster penned. Two days later Foster wrote his mother that, “We have heard nothing of Mid. I suppose he is safe in Abraham’s bosom long since. We will never meet again unless he becomes dissatisfied and comes back. They can never induce him to join their army, he can not stand the fire, we are getting along finely without him.”

One wonders what exactly Foster meant when he wrote that the Federals “can never induce him to join their army?” The United States army was not accepting Black men at that point in the war, so he must have not meant as a soldier, but Foster also stated that Mid “can not stand the fire.” Did Foster question Mid’s ability to be a servant for the Union army? If so, had he not already proved he could fulfill that role? Regardless, it turns out that Foster could not have been more wrong.

It is not known what employment Mid entered into after fleeing slavery for freedom. Perhaps he found a Federal officer to work for as he did for Foster, but for wages. Or maybe he made his way to nearby Washington D.C. and worked in any numerous paid positions. The next historical record that appears for Mid is a draft register in the summer of 1863, noting that he lived in Washington’s Eastern Branch and lists his occupation as “laborer.”

Whatever work Mid entered into, his enlistment in Company G, 23rd United States Colored Infantry came on March 31, 1864, in Washington. His enlistment form gives his full free name as Middleton Foster. It also states he was born in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and that he was 36 years old. Pvt. Foster’s complied military service record notes that he was absent sick in an Alexandria, Virginia, general hospital beginning on July 17, 1864. Pvt. Foster’s illness absence continues noted on each of his muster cards in his records until the regiment mustered out in Texas in November 1865. Did Pvt. Foster receive care in Alexandria’s L’Ouverture Hospital, a facility for Black soldiers? Did he die of some disease while in the hospital and it went undocumented? If so, was he buried in the Contrabands and Freedman’s Cemetery? The most extant list does not include his name on the cemetery records. And if he did survive, a search for post-war records concerning Pvt. Middleton Foster did not produce any results.

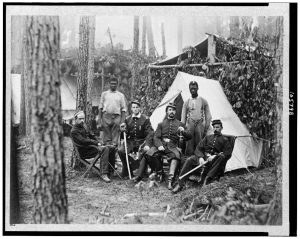

Was Pvt. Foster’s experience unusual? Finding records that confirm a formerly enslaved Confederate camp servant later became a soldier in the United States Colored Troops are fairly rare. But it was certainly not uncommon for self-emancipated men, and some women, who made it into Federal lines, to work as officers’ servants. In addition, some men of color who lived in the free states also started their military careers as servants before becoming soldiers. There are dozens of documented cases that serve as examples.

One of the most well documented individuals who went from Union camp servant to soldier is Sgt. Andrew Jackson Smith. Smith eventually received the Medal of Honor posthumously, but before performing his courageous combat act, he made the bold attempt to secure his freedom and ended up as servant to a Union officer.

Andrew Jackson Smith was born enslaved in western Kentucky on his white father and enslaver’s farm in 1842. When Smith’s father died just before the Civil War began, he became the human property of his half-brother, William Smith, who soon joined the Confederate army. When Andrew learned that William planned to use Andrew and another enslaved man to work for the Confederate war effort, both men decided to escape. After a harrowing journey, they arrived within Union lines. Andrew offered his services to Maj. John Warner of the 41st Illinois Infantry. In early 1862, an army-wide policy was not yet set on what to do about individuals who fled their enslavers and came into military lines, especially in a slaveholding state like Kentucky. Andrew was fortunate that he landed in a sympathetic situation.

While serving as Maj. Warner’s servant, Andrew had the opportunity to experience what war was like firsthand. Although in the role of servant, Andrew remained behind the lines for the Battle of Fort Donelson, at Shiloh during the confusion caused by the Confederate surprise attack, Andrew received a painful spent bullet wound to the right side of his head. Soon after, he received another wound to the left side of his head that ranged under his skin to middle of his forehead which required a doctor to cut it out. Andrew witnessed the terrible destruction of battle to both the landscape and human bodies, but apparently it did not dissuade him from a sense of duty.

Maj. Warner developed an intestinal disorder soon after Shiloh and returned home to Clinton, Illinois to recover. Andrew went with him. When Warner returned to his regiment in May 1862, Andrew remained in Illinois where he found work. As Federal policy progressed toward accepting Black enlistments with the passage of the Militia Act of 1862 and President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Andrew prepared to join up at the first opportunity. When Andrew learned about Massachusetts Governor John Andrews raising a regiment of men of color, he left for Chicago and traveled by train to Boston and Camp Meigs. The 54th Massachusetts was full by the time he arrived, so Andrew enlisted in the 55th Massachusetts on May 16, 1863.

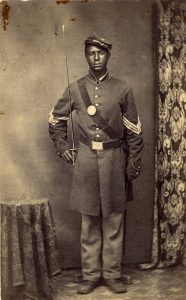

Pvt. Andrew Smith apparently took to soldiering. He received special detail duty during his first months and received promotion to corporal on June 15, 1864. At the Battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina on November 30, 1864, Smith saved the regimental colors after a Confederate artillery shell killed the color bearer. Smith carried the standard throughout the remainder of the battle.

Corp. Smith received a promotion to sergeant in February 1865. Smith mustered out in August 1865. He returned to western Kentucky where he farmed and speculated in real estate until his death in 1932. His descendants accepted his Medal of Honor on his behalf in 2001.

Unlike Andrew Smith, Alexander Heritage Newton was born free on November 1, 1837, in New Bern, North Carolina. Newton grew up fully aware that although not enslaved, he lived as a second-class member of his town’s population. In addition, having an enslaved father was a continual reminder of the burdens and restrictions placed upon those who labored in bondage. In 1857, Newton left North Carolina working as cook on board a ship that took him to New York City.

In 1861, although not allowed to formally enlist at that point in the war, Newton accompanied the 13th New York State Militia, also known as the 13th Brooklyn, “to the front.” In what capacity Newton served the 13th is unknown, but he probably helped the unit as a cook since it was a skill he had previously acquired. However, when the 13th later received a transfer to New York to help quell the draft riots in 1863, Newton ended caught up in the racial violence, but fortunately made his escape to New Haven, Connecticut.

On December 18, 1863, Newton enlisted in Company E of the 29th Connecticut Infantry Regiment, one of the few African American units allowed to keep its state designation (like the 54th and 55th Massachusetts) rather than receive a United States Colored Infantry regimental number. Newton’s enlistment papers show he was just over 5’ 8” tall, with black hair, black eyes, and black complexion. His stated occupation was that of mason. The 26-year-old Newton immediately received the rank of sergeant, and later received an appointment to commissary sergeant. The 29th Connecticut served in the Tenth Corps and then later became a regiment in the all African American Twenty-fifth Corps, Army of the James. The 29th participated in battles at Second Deep Bottom in August 1864, Chaffin’s Farm in early October, and Fair Oaks on October 27, 1864. Newton mustered out with the regiment in October 1865, and became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, serving congregations in several states. He died in 1921 in Camden, New Jersey and rests in Mount Peace Cemetery.

Sources:

Beckman, W. Robert and Sharon S. MacDonald. Carrying the Colors: The Life and Legacy of Medal of Honor Recipient Andrew Jackson Smith. Westholme Publishing, 2020.

Complied Military Service Record for Pvt. Middleton Foster, 23rd USCI, accessed via Fold3.com

Compiled Military Service Record for Sgt. Alexander Heritage Newton, 29th Connecticut Infantry, accessed via Fold3.com

Complied Military Service Record for Sgt. Andrew Jackson Smith, 55th Massachusetts Infantry, accesses via Fold3.com

Contrabands and Freedmen’s Cemetery Memorial. Located at: http://www.interment.net/data/us/va/alexandria/contrabands-freedmens-memorial/contrabands-freedmens-cemetery-records.pdf

Kennedy, A. Gilbert. A South Carolina Upcountry Saga: The Civil War Letters of Barham Bobo Foster and His Family, 1860-1863. University of South Carolina Press, 2019.

Newton, A. H. Out of the Briars: An Autobiography. Reprint, Pamplin Historical Park, 2000.

thanks Tim … great story about three great Americans.