Benjamin Prentiss on the Threshold of Shiloh

The failure of the Union high command to anticipate General Albert Sidney Johnston’s attack at Shiloh still generates controversy and debate. Looking at the evidence it is clear that Brigadier General William Tecumseh Sherman failed to take the warnings seriously, only planning a scouting expedition for April 6. Major General Ulysses S. Grant failed as well by staying at Savannah and formulating no plan of defense. In the days leading up to Shiloh his cavalry had been bested in the war of posts but Grant seemed unmoved. Grant was also more worried about Crump’s Landing, where Major General Lewis Wallace’s division guarded the main supply depot. Major General John McClernand and Brigadier General Stephen Hurlburt had their worries but were ignored and their divisions were in the rear. No one knows what William Wallace, new to division command posted at Pittsburg Landing, thought but he did not have his division ready on April 6.

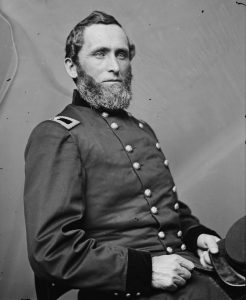

Yet, one wonders about Brigadier General Benjamin Prentiss. He was born in Virginia and attended a military school there, but moved west and lived in Illinois. He was a founder of the Republican Party and a noted orator, but lost a congressional race in 1860. In 1861 he raised troops and commanded the garrison at Cairo, where he oversaw the end of the legal traffic of goods bound south. He was then posted in Missouri and quarreled with Grant, which led to life-long enmity between the two. Major General Henry Halleck did not like Prentiss, but his political connections precluded his removal.

Prentiss’s division, still not fully organized, was the rawest, fresh from camps of instruction, some having only just arrived. There were some veterans though mixed in the ranks. The regiments on hand were the 18th, 21st, and 25th Missouri, 16th and 18th Wisconsin, 12th Michigan, and the 61st Illinois. Prentiss had only two batteries, the 5th Ohio and 1st Minnesota. On April 6 the 15th Michigan and 23rd Missouri were to join the division. Prentiss had no cavalry, which limited his ability to scout ahead although the 11th Illinois Cavalry was nearby but not under Prentiss’ direct command.

What occurred in Prentiss’ division on the eve of battle can be difficult to understand. There were conflicting reports and recollections. Some officers acted out of turn and two men (Everett Peabody and James Powell) who played a crucial role in the opening hours of Shiloh both died, taking with them their side of the story. Added to that Prentiss was quiet for years about Shiloh . When he did did speak out he made some errors and sought to defend his reputation, although he was honest enough to say “We came here to go to Corinth, but Corinth came to us.”

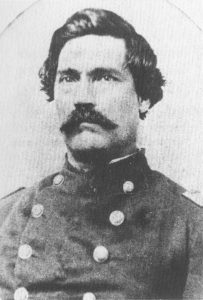

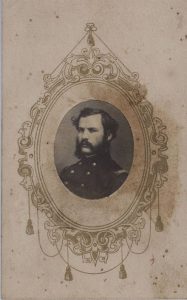

On April 5 Major James Powell of the 25th Missouri was officer of the day and he reported enemy activity. At 4:00 p.m. Prentiss sent out one company of the 18th Wisconsin after Prentiss spoke with David Stuart, who’s brigade was camped nearby and sent out a patrol on April 5. Even more important, Prentiss ordered Colonel David Moore of the 21st Missouri to take companies from the 21st and possibly the 25th Missouri to reconnoiter. Moore reported that a “A thorough reconnaissance over the extent of 3 miles failed to discover the enemy.” The Federals found only traces of Rebel cavalry but were warned by some locals that a large Confederate army was going to attack. Moore reported his findings to Everett Peabody (his brigade commander) and Prentiss ordered the 21st Missouri to have forty rounds and two days worth of rations doled out to each man. Moore declared before his officers “we will have h–– in the morning.”

In reaction to Moore’s report, Prentiss extended and strengthened the picket line. On April 6 Moore would go out with five companies of the 21st Missouri “to sustain the pickets of the Twelfth Michigan Infantry.” On the left two companies of the 18th Wisconsin and in the center, one company each from the 61st Illinois and 18th Missouri would go with orders “to remain until daylight and see if they could not capture some of the marauders that had been engaged in committing depredations immediately in our vicinity.” Prentiss later claimed in 1895 that he reported his fears to Sherman who said “I will guard your front.” This and Moore not running into Johnston’s army, might have made him less apprehensive once the sun set. Captain Gilbert D. Johnson reported to Lieutenant Colonel William Graves of the 12th Michigan around 8:30 p.m. that “he could see long lines of camp fires” and “hear bugle sounds and drums.” Graves, a veteran of Bull Run, informed Prentiss who dismissed the concern, thinking the Rebels were likely just a reconnaissance in force, but he did order Graves to pull back Johnson’s advance company to avoid them being overrun. At 10:00 p.m. Graves and Johnson again met with Prentiss and he was still unconcerned. He took no extra precautions and generally seemed to think he was in no danger. Prentiss later said “I had not the least idea that a general engagement was to have been had on that day.”

Prentiss took more precautions than Sherman although he had less evidence of the Confederate army, which was to the southwest and closer to Sherman. Prentiss can be commended for strengthening his pickets and sending out Moore on patrol on April 5. The wonder is how Moore did not run into the Rebels, the assumption being that he veered to the northwest, closer to Sherman’s camp. Yet, Prentiss did fail to anticipate the firestorm of April 6. What can be said for Prentiss and Sherman is that once the shooting started each man fought like a lion and rightfully won their promotions.

This post comes after doing detailed research with the aid of Mike Maxwell and Hank Koopman. I did not formalize my footnotes as this is not yet ready for professional publication. Instead below are the sources consulted for this post.

War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 53 vols. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. Vol 10. Part 1: 277-278, 282, 283

Baker, Daniel B. “How the Battle Began.” National Tribune, April 12, 1883.

“Federal Veterans at Shiloh.” Confederate Veteran 3, no. 4 (April 1895): 104-105.

Holman, T. W. “The Story of Shiloh.” National Tribune, September 14, 1899.

French, William. “One Regiment that was Not Surprised.” National Tribune, April 12, 1883.

Morton, Charles. “A Boy at Shiloh.” Personal Recollections of the War of the Rebellion, 3: 52-69. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907.

Neal, W.A., ed. An Illustrated History of the Missouri Engineers and the 25th Infantry Regiment. Chicago: Donohue and Henneberry, 1889.

Nickell, Franklin Delano. “Grant’s Lieutenants in the West, 1861-1863.” Dissertation,University of New Mexico, 1972.

Report of the Proceedings and Speeches of the Seventh Annual Reunion and Supper of the Cincinnati Society of Ex–Army and Navy Officers. Cincinnati: Peter G. Thomson, 1883.

Robertson, John. Michigan in the War. Lansing: W.S. George, 1882.

Smith, Carlton L. “A Promising Son is Lost.” Civil War Times Illustrated 24, no. 1 (March 1985): 26-33, 35.

Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Shiloh: Character in Leadership, April 6-7, 1862. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017.

Missouri Historical Society (St. Louis, Missouri)

Henry Cist Papers: Edward Jonas, “With Prentiss at Shiloh”

Sean, what do you think of Edward Cunningham’s work on Shiloh?

It is a very good book, both readable and well researched. Honestly, Shiloh has received good treatment from Daniel, Smith, and Sword as well. There are bad accounts of Shiloh but I tend to find those in books with a larger scope.

The more I read about Shiloh, the more I become impressed with Grant’s amazing performance there–in the face of total disaster.

With total 20/20 hindsight, I guess Grant should have been in Shiloh when the (surprise) attack began. But, as always, he was following his OWN military plan and not just waiting around for the enemy.

Then that very evening of the first day, when everyone else was exhausted and demoralized by the incredible slaughter (who could blame them?), Grant made the key decision. A full on Union attack the next day broke the Confederates and achieved a decisive victory. The most horrific battle in American history (up till then) and, with anyone but Grant, imagine what might have happened?!

We’ll lick ’em tomorrow, said Grant to his astounded, defeated men—and they did.

Grant to me was mixed at Shiloh. He made a lot of mistakes before the battle and those mistakes led to his men hating him after the battle. I think they were right to be angry. That said Grant made good decisions once the firing started. My favorite is on April 7 when he brought up reserves and ordered an attack at Review Field that helped to drive off the Rebels. Shiloh was not Grant at his best, but some of his best qualities were on display.

The biggest surprise in my research has been Buell. He did superbly at Shiloh. After the battle the soldiers loved him and rightfully so. He brought the men that assured victory, led them into battle, and was constantly at the front, inspiring his men and bringing up reserves. Shiloh was his high point. It was down-hill from there for Buell, although that had as much to do with his personality as it did politics and some pretty awful strategic directives from Lincoln, Stanton, and particularly Halleck.

Great post. Regarding Moore’s patrol, is it possible that he went due south which would have taken him to the east of where the Confederates were deploying?

Lets consider his second report dated April 11, 1862 (page 282 of OR Vol. 10, pt. 1):

“In pursuance of the order of Brig. Gen. B. M. Prentiss, commanding Sixth Division, Army of West Tennessee, I on Saturday proceeded to a reconnaissance on the front of the line of General Prentiss’ division and on the front of General Sherman’s division. My command consisted of three companies from the Twenty-first Missouri Regiment—companies commanded by Captains Cox, Harle, and Pearce. A thorough reconnaissance over the extent of 3 miles failed to discover the enemy.”

Seems clear he went towards Sherman’s division and skirted the Rebels. It is curious he found no one though. One person told me he thought Moore was incompetent based on this failure, but he was an aggressive and thorough soldier. I think it was just bad luck and it seems Prentiss ordered him in the direction that turned up nothing. As it is Moore’s failure is one of the bigger what ifs that do not get enough coverage.

Glad you liked the post

Agree on Moore; I certainly don’t see him as incompetent. Good point from his report on his direction; that certainly shows what direction he went.

Nice post BTW … regarding Moore’s recon, land navigation wasn’t the infantry skill that it is today and it’s likely Moore had no maps from which to judge distance … i would question Moore report, albeit a well-intentioned one, that he actually recon’d 3 miles out and then 3 miles back …