Everett Peabody on the Threshold of Shiloh

If it had been left to Brigadier General Benjamin Prentiss then Shiloh might have been the full surprise it was often falsely portrayed as. On the night of April 5, Captain Gilbert D. Johnson and Lieutenant Colonel William Graves of the 12th Michigan tried to warn Prentiss that the Confederate army was on his doorstep. Prentiss was not worried, likely because Colonel David Moore’s patrol turned up nothing on April 5.

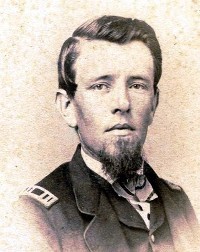

Graves and Johnson next met with Major James Powell of the 25th Missouri and Colonel Everett Peabody, one of Prentiss’ two brigade commanders. Peabody was a thirty-one year old scion of a Massachusetts family that traced its roots to the early colonial days. He was a Harvard graduate, railroad engineer, and scholar fluent in French, Spanish, and German. He also had combat experience, having fought at Lexington where he was severely wounded. Although brave and popular with the soldiers, he was considered difficult and hot-tempered by many officers. At Lexington he nearly fought a sword duel with Colonel James Mulligan.

Powell and Peabody noticed Rebel cavalry at Spain Field on April 4. Peabody personally asked Prentiss if the division should be repositioned for defense and receive some artillery only to be turned down. According to Orderly Sergeant James M. Newhard of the 25th Missouri, Prentiss “hooted at the idea of Johnston attacking us.” Powell on the night of April 4-5 led a small patrol, hoping to nab a Rebel cavalry veddette staying in a house. His patrol could hear the Rebel army moving into position. On the night of April 5, likely after seeing Graves and Johnson, Peabody met with Newhard and his friend Captain Simon S. Evans. After sharing cigars, Peabody declared he would not be taken by surprise. He called in Powell and ordered him to take out a patrol. In one account by Lieutenant William J. Hahn of the 25th Missouri Powell tried to and failed to get permission for a similar patrol from Prentiss, who only relented at Peabody’s insistence. Powell moved out around 11:00 p.m. to capture cavalry and “bring them in out of the wet.” They could hear Confederates moving about everywhere, so Powell fell back.

Right after midnight, the picket line of the 21st Missouri reported hearing Confederate movement, although if Peabody or Prentiss received this report is unknown. What is known is that Powell reported to Peabody that he observed a strong Confederate picket line. Peabody was satisfied that it was General Albert Sidney Johnston’s army. He ordered Powell to take five companies from the 25th Missouri and 12th Michigan, some 400 men, and head out at 3:00 a.m. to engage Johnston. By one account, Peabody doubted he could convince Prentiss of the danger, and declared “they shall not surprise us; there is but one thing for me to do ; that is, to send a small force out and attack them, and so give the alarm to our army.” Peabody sent a messenger to inform Prentiss of the patrol but Prentiss could not be found.

Powell’s patrol moved down a wagon trail in three columns and boasted to the pickets of the 57th Ohio that they were “going to catch some Rebels for breakfast.” Powell’s men would get their wish. Their path was taking them right at Brigadier General S.A.M. Wood’s brigade. Just ahead of Wood’s battle line was Major Aaron Hardcastle’s 280 man 3rd Mississippi Battalion. Hardcastle was a favorite of Johnston and accompanied him in his trek from California in 1861. Johnston personally chose Hardcastle to command the outer line. Ahead of Hardcastle were two cavalry patrols. One was led by Lieutenant F.W. Hammock, drawn from Lieutenant Colonel Richard H. Brewer’s Mississippi and Alabama Cavalry Battalion. Another cavalry group was led by Lieutenant William McNulty.

Between 4:55 a.m. and 5:14 near the Corinth Road, the soldiers of the 12th Michigan spied a horseman. Orders were given to fall back but then the cavalry opened fire. The battle of Shiloh had begun.

In the Federal camp, the reaction was more muted at first. Many thought it was just another picket skirmish or a regiment clearing its guns. William Christie of the 1st Minnesota Battery wrote “Nobody thought that it was anything more than a skirmish; we supposed that soon we should be back again in camp.” Graves spoke to Prentiss as the first shots were heard in Powell’s area. Prentiss was unconcerned for a moment, but as the firing continued he rode up to confront Peabody. Prentiss was furious that Peabody had sent out a long range patrol. If Hahn’s account is correct, then it at first seems curious that Prentiss was angry. However, Prentiss had ordered a night patrol and he received no report from Powell. Prentiss had not authorized a dawn foray. One thing is clear, Peabody and Prentiss had a testy exchange. Prentiss carried a grudge against Peabody long after Shiloh, and made only one mention of him in his official report and only passingly in a speech made after the war. Prentiss instructed Peabody to hold while the rest of the division formed for battle. Peabody had already been ordered to send Moore out to support the pickets, but at this point he likely ordered Moore to directly support Powell. As Moore came up, he ran into Captain Edward Saxe of the 16th Wisconsin. Earlier, Saxe’s picket line ran when the firing began but he rallied them and said “Boys, we will fall in on the right and lead them.”

Back at the front, Wood ordered Hardcastle to hold as he formed the brigade. Once that was accomplished Hardcastle fell back, his place taken by the 8th Arkansas and 9th Arkansas Battalion. At 6:30 a.m. Powell fell back past Seay Field where he found Moore and Saxe. Private Joseph Ruff of the 12th Michigan recalled that Moore “rated us cowards for retreating.” The men warned Moore “not to be too bold or he would get into trouble.” Moore though would not be dissuaded. Known for his short temper and command of swear words, he hated Confederates and was reprimanded for allowing his men to shoot at civilians. He was not cleared of charges until April 4. He sent back a pugnacious request to Prentiss: “If you will send the balance of my regiment to me, by thunder, I will lick them!” Instead Moore was driven back, suffering a serious wound. In the fighting Saxe died, the first officer to perish at Shiloh.

Despite the confusion caused by contradictory sources, it is clear that Peabody and Powell succeeded in giving the Union army valuable time to form a battle line before the Rebels attacked. However, Prentiss’ line would not hold. His division was outnumbered with exposed flanks and no good defensive terrain. Yet, he held long enough for the rest of the army to form and Prentiss’ men inflicted considerable losses on the Confederates, who had to commit four brigades before Prentiss gave way. In the fierce fighting Peabody was killed as his brigade collapsed. Powell did not long out last him. He died in the early afternoon defending the famed “Hornet’s Nest.” One reason the role of Peabody and Powell was forgotten was that each man died. Prentiss did not even fully understand what happened and he asserted that the battle was really begun by Moore. Yet, over time the truth came out, and Peabody and Powell are today heavily praised for their actions at Shiloh, their vigilance standing in contrast to Grant, Sherman, and Prentiss.

This post comes after doing detailed research with the aid of Mike Maxwell and Hank Koopman. I did not formalize my footnotes as this is not yet ready for professional publication. Instead below are the sources consulted for this post.

War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 53 vols. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. Vol 10. Part 1: 277-278, 280, 282, 283, 284, 576-57, 600, 603

Anders, Leslie. The Twenty-First Missouri: From Home Guard to Union Regiment. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1975.

Baker, Daniel B. “How the Battle Began.” National Tribune, April 12, 1883.

Carothers, J.S. “Forty-Five Mississippi Regiment.” Confederate Veteran 6, No. 4 (April 1898): 175.

Christie, Thomas and William. Brother of Mine: The Civil War Letters of Thomas & William Christie. Edited by Hampton Smith. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2011.

Cunningham, M.H. “Some Interesting Letters.” National Tribune. April 10, 1884.

“Federal Veterans at Shiloh.” Confederate Veteran 3, no. 4 (April 1895): 104-105.

Gordon, Edward A. “A Graphic Picture of the Battle of Shiloh.” National Tribune, April 26, 1883.

History of Lewis, Clark, Knox and Scotland Counties, Missouri. St. Louis and Chicago: The Goodspeed Publishing Co. 1887.

Holman, T. W. “The Story of Shiloh.” National Tribune, September 14, 1899.

Freeland, H.C. “Alpha of Shiloh.” National Tribune, July 26, 1900.

French, William. “One Regiment that was Not Surprised.” National Tribune, April 12, 1883.

Jones, D. Lloyd. “The Battle of Shiloh.” In War Papers, 4: 51-60. Milwaukee: Burdick and Allen, 1914.

Morton, Charles. “A Boy at Shiloh.” Personal Recollections of the War of the Rebellion, 3: 52-69. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907.

Neal, W.A., ed. An Illustrated History of the Missouri Engineers and the 25th Infantry Regiment. Chicago: Donohue and Henneberry, 1889.

Orr, William M. “A Picket Corrects General Veatch.” National Tribune, April 12, 1883.

Report of the Proceedings and Speeches of the Seventh Annual Reunion and Supper of the Cincinnati Society of Ex–Army and Navy Officers. Cincinnati: Peter G. Thomson, 1883.

Rich, Joseph W. The Battle of Shiloh. Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa, 1911.

Robertson, John. Michigan in the War. Lansing: W.S. George, 1882.

Roman, Alfred. The Military Operations of General Beauregard in the War Between the States, 1861-1865. 2 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1884.

Ruff, Joseph R. “Civil War Experiences of a German Emigrant As Told by the Late Joseph Ruff of Albion.” Michigan History Magazine 27 (1943): 271-301.

Shambaugh, Benjamin F. ed. Some Comments Upon J. W. Rich’s Discussion of the Battle of Shiloh. Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa, 1914.

Shea, John Gilmary. The American Nation Illustrated in the Lives of Her Fallen Brave and Living Heroes. New York: Thomas Farrell & Son, 1862.

Starr, N.D. and T.W. Holman. The 21st Missouri Regiment. Fort Madison, IA: Roberts & Roberts, 1899.

Smith, Carlton L. Peabody at Shiloh: A Short Study of Courage and Injustice. Harvard: Tahanto Trail, 1983.

Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Shiloh: Character in Leadership, April 6-7, 1862. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017.

Williamson, David. The Third Battalion Mississippi Infantry and the 45th Mississippi Regiment. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004.

Yard, M.H. “Shiloh Correspondence.” National Tribune, April 17, 1884.

Yeary, Mamie, ed. Reminiscences of the Boys in Gray: 1861-1865. 2 vols. Dallas: Smith & Lamar, 1912.

National Archives and Records Administration (Washington, D.C.)

Entry 193 Compiled Service Records: F.W. Hammock (Brewer’s Mississippi and Alabama Battalion)

Newberry Library (Chicago, Illinois)

Oliver Perry Newberry Papers (25th Missouri)

Shiloh National Military Park (Shiloh, Tennessee)

I.P. Rumsey File: I.P. Rumsey Memoir

3rd Mississippi Battalion File: Charles Van Adder, “Colonel Aaron B. Hardcastle”

State Historical Society of Missouri (Columbia, Missouri)

Robert Van Horn Papers: William A. Morton, “Personal Experiences in the Battle of Shiloh” (25th Missouri)

University of Michigan – Bentley Library (Ann Arbor, Michigan)

William C. Claxton “Thirty-Nine Years After Shiloh.” (25th Missouri)