Emily Parsons: “To have a ward full of sick men under my care is all I ask”

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome back Tonya McQuade

in St. Louis, Missouri [2]

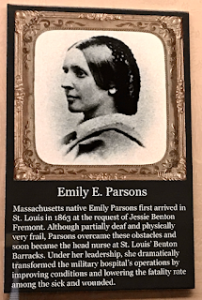

The display caught my attention because Emily served at Benton Barracks General Hospital during the time my great-great-great grandfather, James Calaway Hale, was there recovering from illness after spending time in Helena, Arkansas, with the 33rd Regiment, Missouri Infantry. His first of several letters from the hospital, which I am working on incorporating into a book, is dated June 23, 1863.

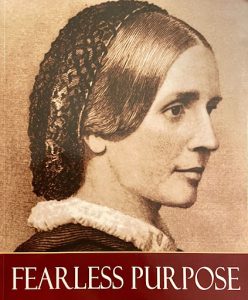

Elizabeth wrote many letters to her parents during her time as a nurse. After she died in 1880, they published those letters in a book titled Fearless Purpose: Memoir of Emily Elizabeth Parsons to help raise money for the Cambridge Hospital, which Emily had founded in Massachusetts. However, Emily had already gained notice in L.P. Brockett and Mary Vaughn’s Woman’s Work in the War: A Record of Heroism, Patriotism, and Patience (1867), the first book written to acknowledge women’s contributions to the Civil War:

[Emily Parson] consulted with Dr. [Morrill] Wyman [1812-1903], of Cambridge, how she could acquire the necessary instruction and training to perform the duties of a skillful nurse in the hospitals. Through his influence with Dr. Shaw, the Superintendent of the Massachusetts General Hospital, she was received into that institution as a pupil in the work of caring for the sick, in the dressing of wounds, in the preparation of diet for invalids, and in all that pertains to a well-regulated hospital….

It was the duty of the nurses to attend to the special diet of the feebler patients, to see that the wards were kept in order, the beds properly made, the dressing of wounds properly done, to minister to the wants of the patients, and to give them words of good cheer, both by reading and conversation – softening the rougher treatment and manners of the male nurses by their presence, and performing the more delicate offices of kindness that are natural to women.

In this important and useful service these nurses, many of them having but little experience, needed one of their own number of superior knowledge, judgment, and experience, to supervise their work, counsel, and advise them, instruct them in their duties, secure obedience to every necessary regulation, and [ensure] good order in the general administration of this important branch of hospital service. For this position Miss Parsons was most admirably fitted, and discharged its duties with great fidelity and success…. The nurses under Miss Parsons influence became a sisterhood of noble women, performing a great and loving service to the maimed and suffering defenders of their country. [3]

It’s easy to read this description and forget that Emily Parsons, due to an injury when she was young, was blind in one eye and had poor vision in the other; had limited hearing ability due to the effects of scarlet fever; and suffered pain in her ankle due to another injury as a young woman. Despite these physical limitations, she trained as a volunteer at the Massachusetts General Hospital for eighteen months after the Civil War began, worked at Fort Schuyler Hospital on Long Island in New York from October to December 1862; served aboard the City of Alton hospital steamship from February to March 1863, where she nursed the sick and injured from the Battle of Vicksburg in Mississippi; and supervised and worked as a nurse for a year and a half at Benton Barracks General Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. She only returned home in August 1864 after she became so ill, she could no longer work and needed time to recover.

In describing her work at Fort Schuyler Hospital, Emily wrote: “To have a ward full of sick men under my care is all I ask; I should like to live so all the rest of my life…. The good that is being done now is perfectly beautiful. I have done my work, and I think I have done it pretty well too. It is the opinion of most of those who are now over these things that the ladies who do them voluntarily do them better than hired nurses, and they like to secure our services.” [4]

Upon boarding the City of Alton hospital ship in St. Louis in February 1863, Emily was overwhelmed by the “sense of confusion and dirt, and soldiers,” but she was also extremely impressed by what she saw: “I never before was among people who took it so seriously, because I never was where the war was around us, nor ever before was going into the midst of it; and this makes us realize all that is at stake and what we are doing. Self has to be put down more and more, and the work before us must take complete possession of our minds: that is not easy, but necessary.” [5]

On the way to Vicksburg, the ship stopped in Helena, Arkansas, where James C. Hale was stationed with his Regiment and where MANY men had died from sickness and disease. James – already suffering from dysentery and rheumatism – had been forced to stay behind in late February when his regiment joined Brigadier General Leonard Ross’s expedition to Fort Pemberton, Mississippi, down near Yazoo Pass. It’s possible he encountered Emily during her visit. Three months later, he was transported from Helena to the hospital in St. Louis.

As Emily wrote to her parents in late February: “We are now at Helena; look on the map and you will see it. Imagine living in the midst of what the children call a ‘dirt pie,’ and you will have an idea of the condition of the people!” [6]

According to historian Rhonda Kohl’s study of the Army of the Southwest at Helena from July 1862 to January 1863, “Sickness did not abate over the three and a half years of Federal occupation as Helena became known as one of the most insalubrious locations in the Union…. The four main diseases that beset the soldiers [were] dysentery, malaria, typhoid, and typhus…. The soldiers became unserviceable, and many died, because of the lack of understanding by medical authorities of the etiological cause of the disease, the relationship among sanitation, the environment and health, and the types of drugs used.” [7]

Parsons herself contracted malaria on this voyage and was ill for several weeks upon her return to St. Louis. She continued to suffer from bouts of related illness for the rest of her life. As she wrote to her parents: “You have no conception of the state of the boat when we left it. Hercules might have cleaned it, nobody else could; it was awful!” [8]

Once recovered, Emily took up her work at Benton Barracks General Hospital in St. Louis, telling her parents: “I suppose we shall by and by have two thousand patients. Some of the men are sinking; it is sad to see it. They are very good and patient, but so subdued sometimes by their long suffering, it is very sad; you have no idea of the weariness produced by long, sad sickness away from home and woman’s care. The peculiar sort of submissiveness it causes is like that of a poor tired child who wants somebody to take care of him, and is too weak to do for himself.” [9]

On June 21, 1863 – just two days before James wrote his first letter from the hospital – Emily wrote: “Yesterday we received a number of men from Memphis – poor, sick, and wounded fellows. We are booked for a thousand more, I suppose, from down the river” [10]. Somewhere among those “poor, sick, and wounded fellows” was James. It made me happy to know he had such a kind and compassionate nurse looking after him.

It also made me thankful for the social crusader Dorothea Dix, under whose leadership more than 3,000 women served as paid nurses in the North and the South. A week after the firing on Fort Sumter, Dix – who had already made a name for herself advocating for people living with mental illnesses – volunteered to form an Army Nursing Corps. She was appointed Superintendent of Nurses for the Union Army by Secretary of War Simon Cameron. In this role, she organized hundreds of women volunteers, established and inspected hospitals, and raised money for medical supplies.

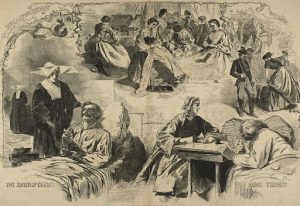

Without the service of these female nurses, many more soldiers would have succumbed to their injuries and illnesses, and many would have spent their final days in fear, pain, loneliness, and despair. Early in the war, Harper’s Weekly recognized this and published a drawing titled “The Influence of Women,” showing how women filled many important roles in the war effort, “from sewing shirts and knitting socks as part of the sanitary commission, to washing clothing for soldiers as camp aides.” [11]

Front and center, The Harper’s Weekly picture features women serving as nurses – “Sisters of Charity” – treating wounded soldiers and writing letters for them, sending “Home Tidings” to their families during the Civil War to help keep their hope alive.

Tonya McQuade is an English Teacher at Los Gatos High School and lives in San Jose, California. She is a great lover of history, frequently visiting museums and historical sites with her husband and children, as well as reading and teaching historical texts, literature, and primary source documents. After acquiring 50 family Civil War letters in 2022, Tonya began researching the American Civil War in Missouri. She is currently working on a book incorporating the letters with historical commentary, titled A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri. Tonya earned B.A. degrees in English and Communication Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and served there as a writer and editor for the student newspaper, the Daily Nexus, for four years. She also earned her Single Subject Teaching Credential in English at UCSB and later her M.A. in Educational Leadership from San Jose State University.

Endnotes:

- Cover Photo from Parsons, Theophilus, and Emily Elizabeth Parsons. Fearless Purpose: A Blind Nurse in the Civil War (Abridged, Annotated). Edited by Theophilus Parsons, Big Byte Books, 2015.

- Photo by Tonya McQuade. Nursing Display, Missouri Civil War Museum, St. Louis, Missouri, April 2022.

- Brockett, L.P. and Vaughn, Mary. Woman’s Work in the War: A Record of Heroism, Patriotism and Patience (1867). Project Gutenberg Ebook, 2007, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/21853/21853-h/21853-h.htm.

- Parsons, Theophilus, and Emily Elizabeth Parsons. Fearless Purpose: A Blind Nurse in the Civil War (Abridged, Annotated). Edited by Theophilus Parsons, Big Byte Books, 2015, pp. 28-29.

- Parsons, Theophilus, and Emily Elizabeth Parsons. Fearless Purpose: A Blind Nurse in the Civil War (Abridged, Annotated). Edited by Theophilus Parsons, Big Byte Books, 2015, 35

- Parsons, Theophilus, and Emily Elizabeth Parsons. Fearless Purpose: A Blind Nurse in the Civil War (Abridged, Annotated). Edited by Theophilus Parsons, Big Byte Books, 2015, 36.

- Kohl, Rhonda M. “‘This godforsaken town’: death and disease at Helena, Arkansas, 1862-63.” Civil War History, vol. 50, no. 2, June 2004, pp. 109+.

- Parsons, Theophilus, and Emily Elizabeth Parsons. Fearless Purpose: A Blind Nurse in the Civil War (Abridged, Annotated). Edited by Theophilus Parsons, Big Byte Books, 2015, p. 39.

- Parsons, Theophilus, and Emily Elizabeth Parsons. Fearless Purpose: A Blind Nurse in the Civil War (Abridged, Annotated). Edited by Theophilus Parsons, Big Byte Books, 2015, 75.

- Parsons, Theophilus, and Emily Elizabeth Parsons. Fearless Purpose: A Blind Nurse in the Civil War (Abridged, Annotated). Edited by Theophilus Parsons, Big Byte Books, 2015, 68.

- Backus, Paige Gibbons. “Female Nurses During the Civil War.” American Battlefield Trust, 20 October 2020, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/female-nurses-during-civil-war.

- Backus, Paige Gibbons. “Female Nurses During the Civil War.” American Battlefield Trust, 20 October 2020, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/female-nurses-during-civil-war.

Another great post–informative, fresh–and highlighting the “B List” of ACW heroes. Huzzah!

Thanks, Meg! I definitely believe it took some heroic patience, calm, and courage to be a nurse in the Civil War – and the skill and knowledge Emily Parsons brought to her work certainly helped!

Many people, female and male, have an inner desire to help, usually people, but just help. Thanks are owed to all of these great individuals, then and now. Great article about a great lady. Thanks.