A Walk on the “First Day at Chancellorsville” Battlefield on the 160th Anniversary

To commemorate the 160th anniversary of the start of the battle of Fredericksburg, I took a walk today along the hiking trail on the first day’s battlefield. For those who’ve never been able to visit the site, or for those who’d like to do so virtually on this anniversary, I took photos along the way, which I thought I’d share. I’ve tried to reproduce the wayside markers large enough so that you can read the text for yourself, which will give you an excellent overview of the first day’s fighting.

We’ll start in the plaza next to the Spotsylvania County Museum. Here, the American Battlefield Trust—which preserved and owns the land—has erected kiosks that explain the history of the battlefield and honor those who’ve made contributions to local preservation efforts at Chancellorsville and the Wilderness.

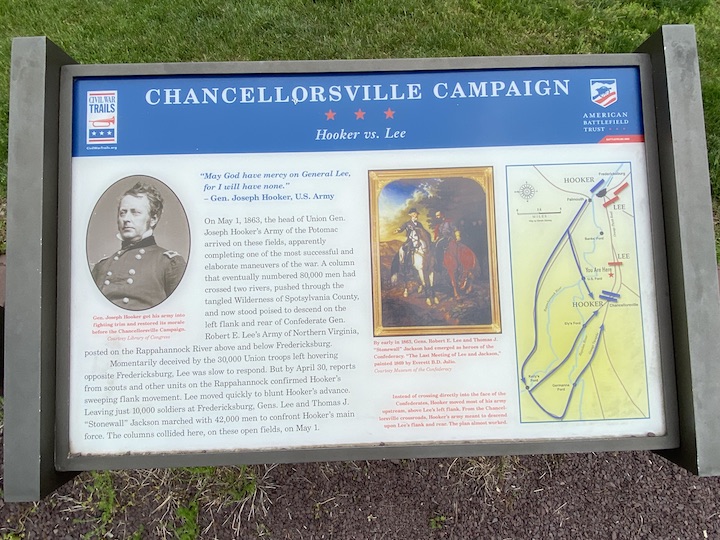

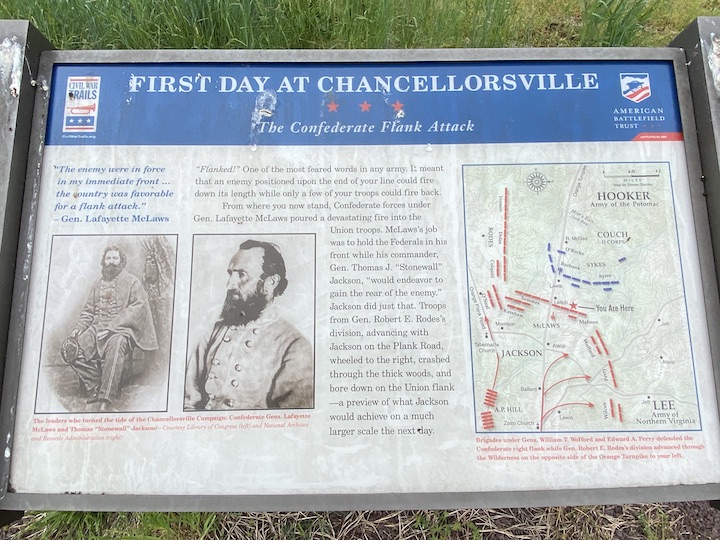

Several wayside markers provide an overview of the Chancellorsville campaign to help prep visitors for their hike:

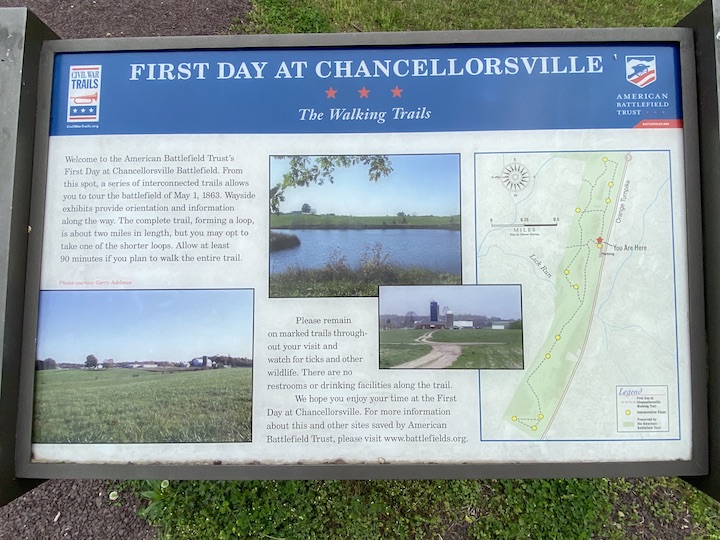

The walking path starts here, as well. A wayside offers a quick overview and trail map:

Waysides along the way—indicated by the yellow dots on the map—provide interpretation.

Waysides along the way—indicated by the yellow dots on the map—provide interpretation.

And off we go, heading east….

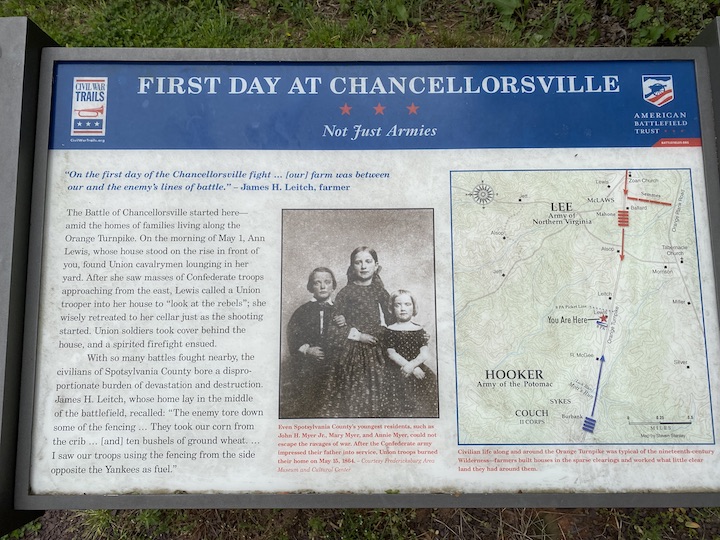

Before this was a battlefield, this was a farm. The first wayside on the trail reminds us to keep the civilians in mind as we talk about the military action here:

* * *

* * *

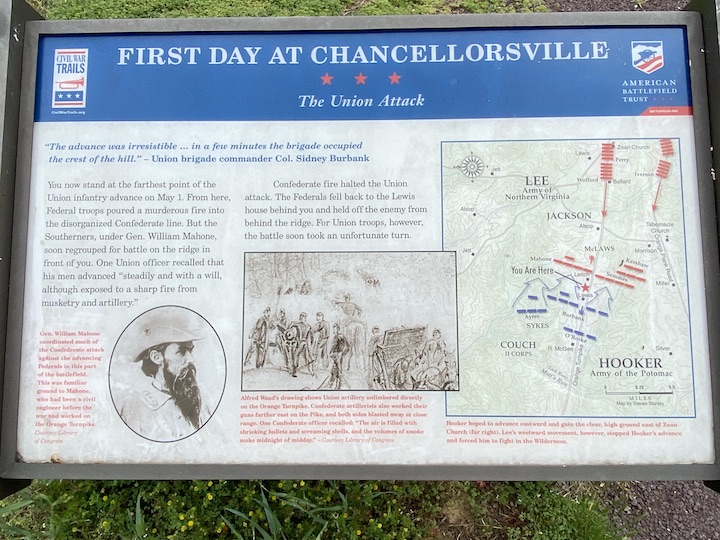

Over the winter of 1863, Confederates built earthworks along a piece of high ground called Zoan Ridge as the rear guard for their winter encampment in Fredericksburg. Today, a Home Depot sits in that area on the north side of Route 3, although Zoan Church church sits on the south side of the road, on the crest of the ridge itself. From this area, Stonewall Jackson ordered Brig. Gen. William “Little Billy” Mahone’s men to advance to meet the oncoming Union column along the Orange Turnpike. The wayside indicates the area where the meeting engagement took place:

The path passes an old barn and rounds a corner. Here’s the view from the easternmost spot along the path, looking east toward Zoan Ridge:

The path passes an old barn and rounds a corner. Here’s the view from the easternmost spot along the path, looking east toward Zoan Ridge:

The path circles round and—lo!—the first appearance of Stonewall Jackson on the Chancellorsville battlefield:

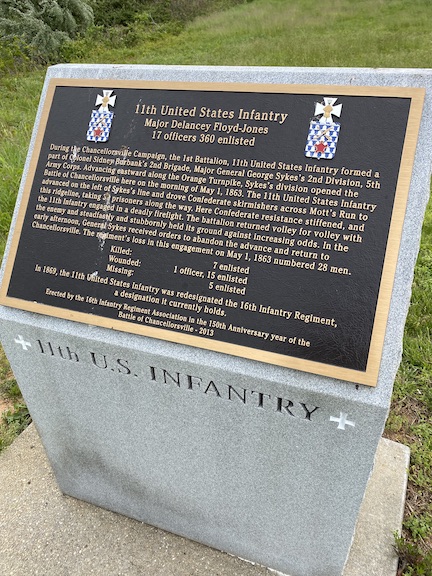

A little farther down the path, you’ll find a monument to the 11th United States Regulars. The monument is facing folks because it’s oriented in the direction the Regulars advanced from, marking the farthest point they advanced to. Here’s what the face of the monument looks like:

A little father beyond, the trail plunges into an area of dense foliage:

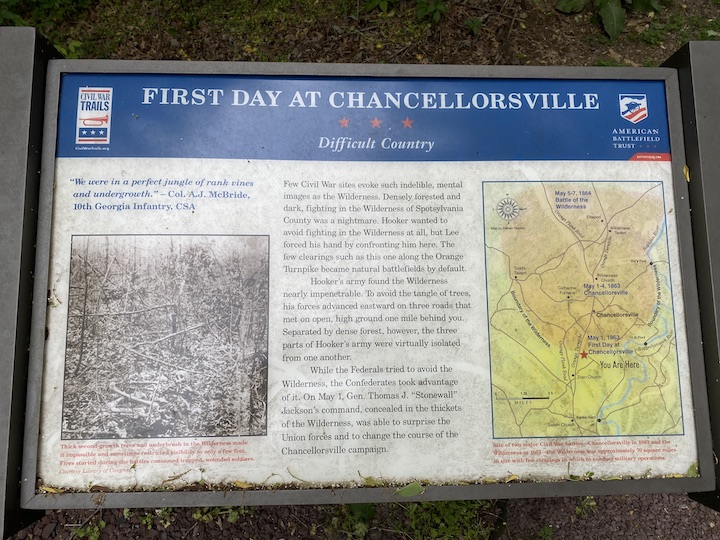

This is one of my favorite spots on the entire battlefield because it’s the one place you can see what the Wilderness actually looked like in 1863 and 1864. Most of the area’s forests have matured considerably since the Civil War. This area looks more like the Wilderness because, as part of the preservation efforts in the early 2000s, this area was re-planted in an effort to reestablish the historic treeline. The result essentially replicates the kind of second-growth forest that made up the Wilderness. A wayside explains:

The path eventually winds out of the heavy brush and into a less-dense area. Along the backside of a hill, you’ll find the next wayside:

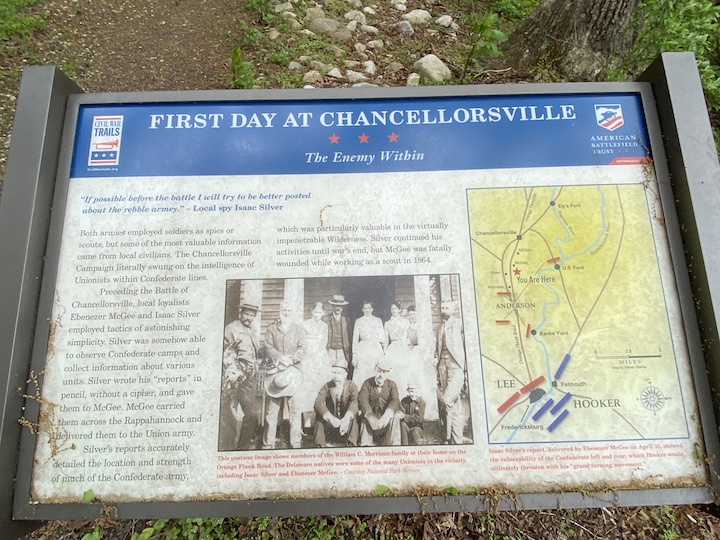

Fittingly, this sign—which seems hidden away—talks about the divided loyalties of some of the local families. Some Union sympathizers acted as important sources of intelligence for the Union army:

The path finally bursts out onto an open hillside. Although farmer’s crops abound, the path winds around to the south side of the hill, offering some excellent views:

The path passes under a buzzing powerline and comes to a T, where we’ll take a right (taking a left will lead us back to the parking lot). Because of the manner in which the path is cut, the intersection looks more like a big U-turn than a T:

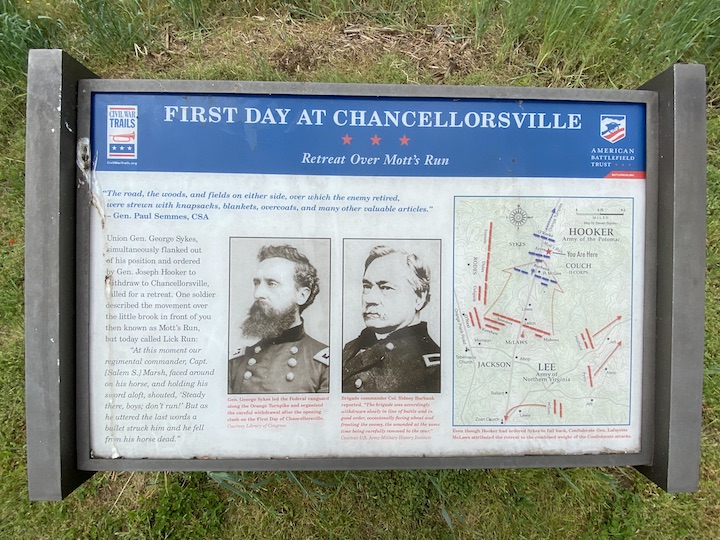

At one point this battlefield was called the Lick Run battlefield, named after the small stream (also called Mott’s Run) that cuts across the middle of the battlefield:

Beyond, the path ascends the next long slope:

Beyond, the path ascends the next long slope:

Driven back from their farthest point of advance, Federals rallied on this high ground. It’s an excellent position, and had Union commander Joe Hooker not ordered his men to pull back, they might’ve held out here all day.

Driven back from their farthest point of advance, Federals rallied on this high ground. It’s an excellent position, and had Union commander Joe Hooker not ordered his men to pull back, they might’ve held out here all day.

I’m reminded of the crucial preservation work the American Battlefield Trust has done in preserving this ground for us:

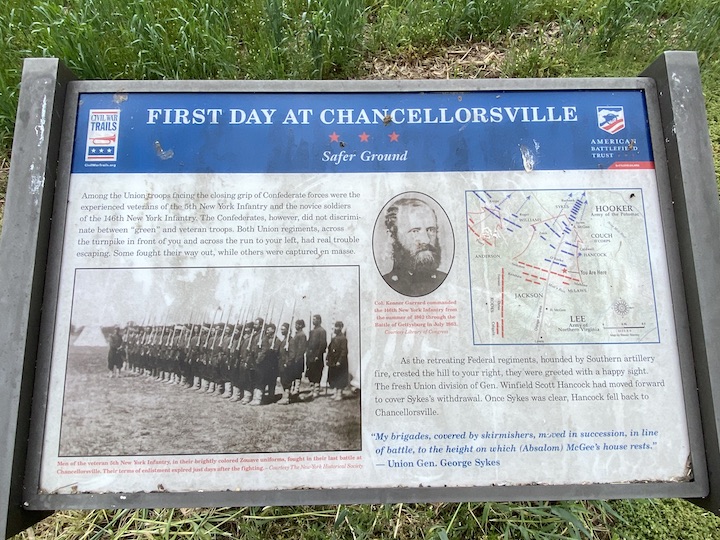

At the top, another wayside awaits. This one explains the strength of the Union position here:

At the top, another wayside awaits. This one explains the strength of the Union position here:

This is a great spot to turn and look back at the ground Confederates would have had to cross to get at Federals perched on this high ground:

Imagine the Confederate assault descending that far open slope, trying to muddle through Lick Run at the bottom, losing their momentum as they tried to shuffle back into alignment, and then advancing up that long open incline. All they while, they would have made perfect artillery targets.

Imagine the Confederate assault descending that far open slope, trying to muddle through Lick Run at the bottom, losing their momentum as they tried to shuffle back into alignment, and then advancing up that long open incline. All they while, they would have made perfect artillery targets.

Lafayette McLaws would have put pressure on the Union right here, but I never cease to wonder how that fight would have played out, particularly if Union reinforcements had been allowed to advance. (Winfield Scott Hancock was at the vanguard of those men, too!)

The path passes a small grove of trees, under which a small family cemetery sits:

This is also a good area to be reminded of the value of the tree plantings on the eastern end of the battlefield. Here, the tree plantings were more sparse, and as a result, they don’t shield the large housing development on the far side the way the new treeline screens them to the east:

This is also a good area to be reminded of the value of the tree plantings on the eastern end of the battlefield. Here, the tree plantings were more sparse, and as a result, they don’t shield the large housing development on the far side the way the new treeline screens them to the east:

The path crosses a road—use caution!—that offers access to the development:

The path crosses a road—use caution!—that offers access to the development:

The path can be hard to spot, but it’s on the far side of the small clearing. A house once stood here, removed because it was not historic. Cross the patch of dirt and keep hiking:

The path can be hard to spot, but it’s on the far side of the small clearing. A house once stood here, removed because it was not historic. Cross the patch of dirt and keep hiking:

Federals continued to fall back through this area toward a more consolidated position around the Chancellorsville intersection to the west:

Federals continued to fall back through this area toward a more consolidated position around the Chancellorsville intersection to the west:

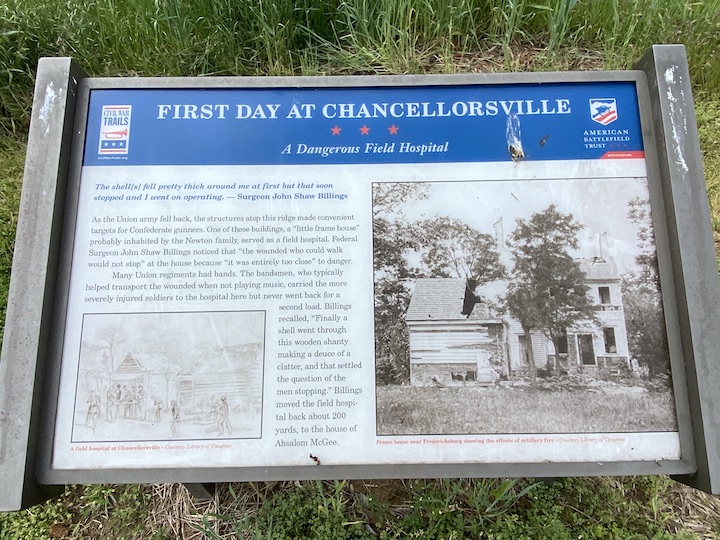

Federal wounded had sought shelter in some of the homes in this area, which proved especially dangerous:

Federal wounded had sought shelter in some of the homes in this area, which proved especially dangerous:

We’re heading into the home stretch:

We’re heading into the home stretch:

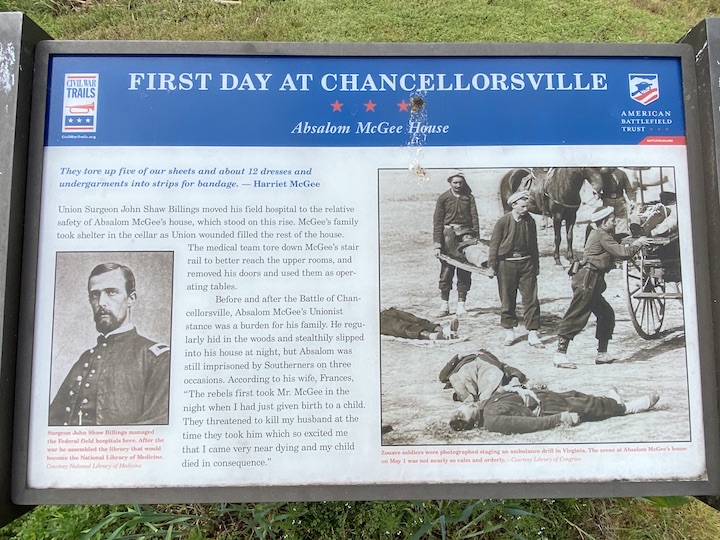

The next wayside also provides the story of another home here along the road:

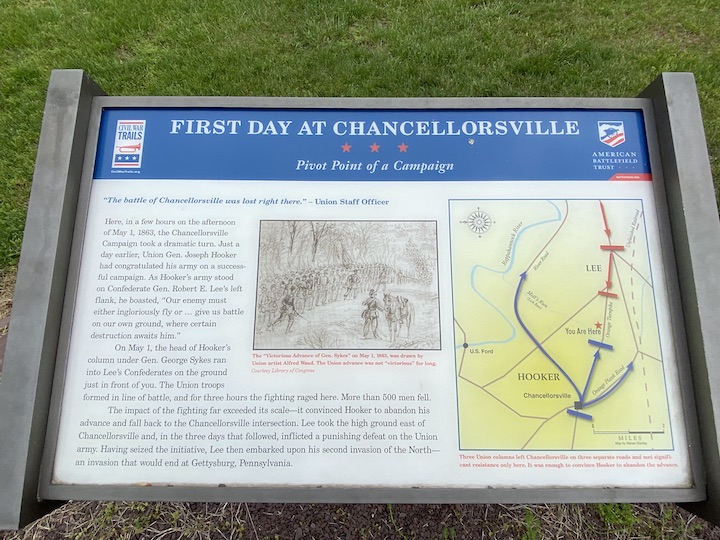

Fittingly, the walking trail ends with a sign about the end of the first day:

Fittingly, the walking trail ends with a sign about the end of the first day:

That story of the legendary “Cracker Box Meeting,” depicted in the sketch on the sign, took place at an area now called the Lee-Jackson Bivouac Site, located just a short drive down McLaws Drive. You can see McLaws Drive from this part of the trail:

That story of the legendary “Cracker Box Meeting,” depicted in the sketch on the sign, took place at an area now called the Lee-Jackson Bivouac Site, located just a short drive down McLaws Drive. You can see McLaws Drive from this part of the trail:

Now that we’re at the western-most point on the trail, it’s a good opportunity to turn eastward and look back across the First Day at Chancellorsville battlefield:

It’s about a mile to get back to the parking lot, so I’d best get walking….

It’s about a mile to get back to the parking lot, so I’d best get walking….

————

You can also join in on my walk from 2018 here.

You learn about the treeline restoration in 2006 here.

Consider donating to the American Battlefield Trust to support battlefield preservation.

Excellent tour, Chris! A great way to walk off your English Pub Crawling adventures…

Chris, thanks for the tour. I walked your walk ten years ago on the 150th, and your photos and comments rekindle the memories. Moreover, with my ten additional years of age, I’m most grateful that you’re making the hike for my benefit and that of our other viewers. I’m looking forward to seeing you at Stevens Ridge in August. Regards, Bill

Thanks for the guided tour

Nice to walk the very interesting trail with you. Hope to do it myself sometime. Thank you.

My husband and I walked that rail several years (when that house was still there). I remember when we walked up the hill, my husband imagined and pretended that the Confederate advance devolved into an exhausted slap-fest with plenty of wheezing.

Love this. I grew up across from the farm the trail is on. We found bullets all the time as kids.You did a great job of presenting this.

Might want to have someone do some editing on your posts.