The CSS Alabama Opens 1863 With a Bang, Part 2

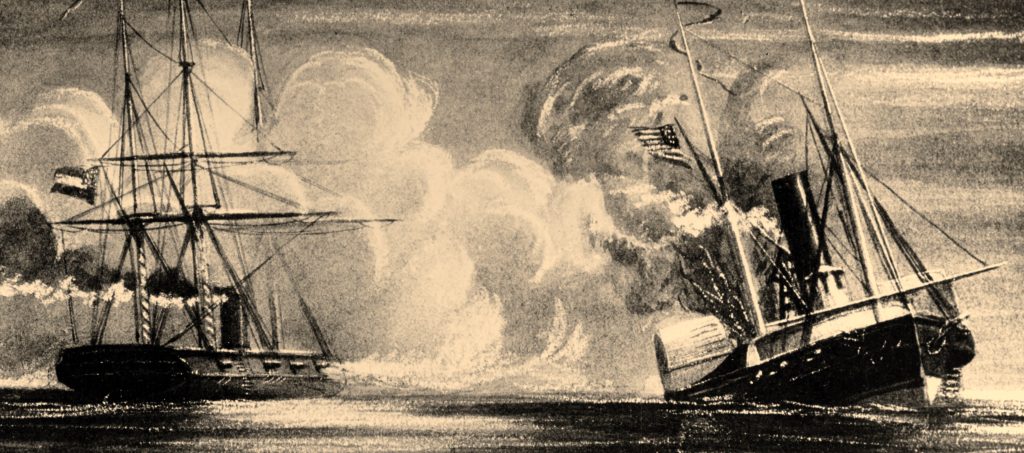

In Part 1, the Confederate commerce raider CSS Alabama confronted a Union squadron off the coast of Galveston on Sunday, January 11, 1863. Captain Raphael Semmes lured a single enemy warship, USS Hatteras, away from her consorts and took her under fire.

An Alabama officer recorded the scene: “Twas a grand though fearful sight to see the guns belching forth, in the darkness of the night, sheets of living flame, the deadly missiles striking her side…her whole side lit up.” As Semmes had surmised, the Yankees were attempting to recapture Galveston. He hoped to disrupt their plans.[1]

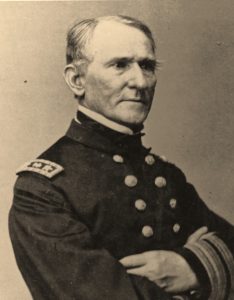

Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, commanding the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, had dispatched Commodore Henry H. Bell with six war vessels to that vital Texas port.

Bell’s command reflected the mongrel mix of Union blockaders, which included the few prewar U.S. Navy assets old and modern, new warships designed and rapidly constructed as the fleet expanded, and most abundantly, purchased and leased civilian conversions of all shapes and sizes enlisted for the emergency.

The latter included coastal traders, ferries, tugs, and other inshore service vessels—light of draft with one or a few guns to counter unarmed runners. They lacked the heavier framing and planking of a true man-of-war.

Steam machinery on civilian vessels usually was on the main deck above the waterline rather than protected in the hold. Many mounted fragile paddle wheels on the side and walking-beam structures thrusting above, all of which made them vulnerable to shot and shell.

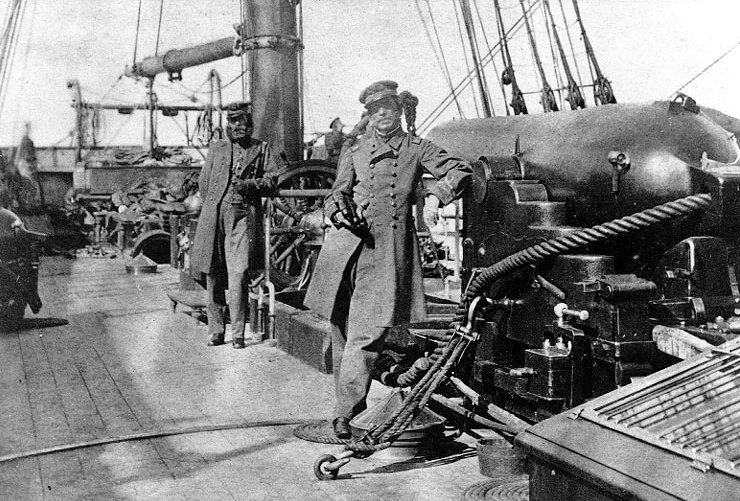

Bell’s flagship was USS Brooklyn, a state-of-the-art, wooden hulled, steam screw sloop-of-war built just pre-war as the U.S. Navy competed resolutely in the ongoing European naval arms race. Like all such, she was of traditional sailing warship design incrementally improved over centuries, but little changed except for the addition of steam propulsion.

Brooklyn (233’ long, 2,532 tons) was formidably armed with one 10” and twenty 9” Dahlgren smoothbores, among the most advanced naval weapons. Sloops-of-war were the smallest ocean-going warship class roughly equivalent to destroyers today. The general term “gunboat” applied to anything smaller.

In Bell’s squadron, two new constructions—USS Sciota and USS Cayuga—were “90-day gunboats,” hurriedly fabricated with 22 sisters during the buildup in 1861. They were smaller versions of Brooklyn (158’ long), lighter (691 tons), more lightly armed (3 guns), and of shallow draft for inshore work. These gunboats saw hard and effective service.

Bell’s other hulls were conversions. The USS New London was a small, screw merchantman (125’ long, 221 tons) and the USS Clifton was a New York sidewheel ferry (892 tons). Hatteras was an iron-hulled, sidewheel merchantman with a walking-beam engine, the largest of the three (210’, 1,144 tons). She mounted four 32-pounders and a 20-pounder.

The Union squadron had arrived the day before, Saturday, January 10, and commenced bombardment of the town. One officer wrote to his father: “Galveston is a doomed town; the disgrace attending the capture of the Harriet Lane must be wiped out, and vengeance upon its butchers and captors will be awful.”[2]

Most Confederate commerce raiders also were lightly armed civilian conversions, but Alabama was an exception, purpose-built to a British gunship design with a warship hull. She was similar in size, speed, and armament to her eventual nemesis, the USS Kearsarge.

Alabama was equipped with six 32-pounder smoothbores (three to a side) and two pivot cannons, a massive 100-pounder Blakely rifle and an 8-inch smoothbore, both of which could fire to either beam. Semmes would not have wished to take on Brooklyn, but he outmatched the others—along with the element of surprise—and he itched for a standup single-ship slugfest like navy heroes of old.

“My men handled their pieces with great spirit and commendable coolness,” the captain recalled, “and the action was sharp and exciting while it lasted; which, however, was not very long.” Thirteen minutes after the first gun, the enemy hoisted a light and fired an off-side gun to signal that he had been beaten.[3]

Semmes ceased fire; the men cheered. Lieutenant Commander Homer C. Blake called over from Hatteras to report his ship sinking and boats destroyed. He needed immediate assistance. The crew was beginning to panic.

Upon his earlier approach in the dusk, Blake had concluded from the newcomer’s rig and outline that she probably was Alabama, a much faster vessel even though they were catching up with her. Smelling a ruse, he cleared for action, readied for “a determined attack and a vigorous defense,” and dispatched a boat to verify her identity.

Acting Master Leander H. Partridge with his boat crew had just rowed off when Alabama’s broadside erupted. He recalled: “Both [ships] started ahead under full head of steam, exchanging broadsides as fast as they could load and fire.” The boatmen stroked mightily to catch up and rejoin but they were left wallowing in the dark.[4]

Hatteras and Alabama commenced a running parallel fight varying from 100 to as close as 25 yards apart. Musket and pistol pops merged with the roar of big guns. “Firing continued with great vigor on both sides,” reported Blake. “Being well aware of the many vulnerable points of the Hatteras, I hoped, by closing with the Alabama, to be able to board her, and thus rid the seas of the piratical craft.” But the Rebel was too fast.

One shell entered Hatteras in the hold amidships, starting a fire. Another passed through sick bay, exploded in an adjoining compartment, also producing fire. A third penetrated the engine cylinder, filling the engine-room with steam, cutting power to the paddlewheels and fire pumps. The walking beam was shot away.

His ship was “a hopeless wreck upon the waters,” wrote Blake. “I still maintained an active fire, with the double hope of disabling the Alabama and attracting the attention of the fleet off Galveston, which was only twenty-eight miles distant.”

More shells tore off entire sheets of iron and blew gaping holes at the waterline as seas gushed in. Alabama surged ahead beyond the arc of Hatteras guns and prepared to cross her bow for a raking broadside. The ship was sinking and fire progressing. Blake flooded the magazine to prevent an explosion, jettisoned the port battery to keep her afloat a bit longer, threw official books and papers overboard, and surrendered.

Alabama’s boats rescued all aboard. Two Union crewmen were killed and five wounded. Blake: “Two minutes after leaving the Hatteras she went down, bow first, with her [commissioning] pennant at the mast-head, with all her muskets and stores of every description, the enemy not being able, owing to her rapid sinking, to obtain a single weapon.”[5]

Partridge watched from the water. “I discovered that the Hatteras was stopped and blowing off steam, with the enemy alongside for the purpose of boarding. Heard the enemy cheering and knew that the Hatteras had been captured, and thought it was no use to give myself up as a prisoner, and rowed back toward the fleet under cover of darkness, in hopes of giving information of the affair.”

Meanwhile as reported to Admiral Farragut, Commodore Bell observed from Brooklyn as gun flashes lit the southern horizon about 7:15 p.m. along with the boom of guns heavier than any carried by Hatteras. The squadron was underway immediately searching scattered courses up to 70 miles out but finding nothing other than, at daylight, the Hatteras boat with Acting Master Partridge.

Finally, near noon, Bell “discovered two masts of a sunken vessel standing out of water. The tops and yards were awash, topmasts up, and a United States naval pennant gaily flying from the main truck. No ensign was found. The hurricane deck was adrift.”

Concluded the commodore: “[Alabama] has probably destroyed numerous vessels in the track between Key West and New Orleans, and doubtless intends to sweep away the blockading vessels of inferior force along the whole extent of the Gulf coast, trusting to his celerity of movement. Three or four vessels like the Oneida thrown into the Yucatan channel immediately would probably intercept him. The gunboats are not a match for him in force or speed.”[6]

Captain Blake noted in his report, “the great superiority of the Alabama, with her powerful battery and her machinery under the water-line” as well as the “total unfitness [of Hatteras] for a conflict with a regular built vessel of war.” Admiral Farragut would write that Hatteras was “nothing but a frail iron shell, with her machinery all exposed.” [7]

Semmes disagreed. To him they were evenly matched in numbers of weapons, 8 each, and in personnel, about 110. Hatteras outweighed Alabama by 100 tons. His only advantage had been the two big pivot guns, but with them, “Alabama ought to have won the fight; and she did win it, in thirteen minutes—taking care, too, though she sank her enemy at night, to see that none of his men were drowned.” His ship suffered only minor damage and one man wounded.[8]

Commodore Bell called off the Galveston attack. “The unlooked for disaster to the Hatteras weakens my available force too much for me to calculate hopefully upon success.” He was low on coal; some ships had not arrived, and another was sent off with the report for the admiral. The former USS Harriet Lane, also a capable ship, was still in Confederate hands and threatening to escape from Galveston.[9]

Admiral Farragut, upon hearing of the loss, immediately dispatched swift vessels to alert others off New Orleans, Mobile, and Pensacola “to be on the lookout for the pirate in case she makes any attempt to depredate upon our coast.”[10]

Only two of his blockaders potentially could contend with Alabama in speed or battery, USS Oneida and USS R. R. Cuyler. They were needed at Mobile to intercept CSS Florida, which was expected to attempt an escape from that port any day (and soon succeeded). Florida would prove to be the second most effective commerce raider.

Counting Harriet Lane, the admiral faced the disturbing prospect of three aggressive and elusive Rebels loose in the Caribbean gunning for Union commerce and disrupting the blockade. He also notified the Atlantic squadron in hopes they could intercept Alabama when she came out.

Semmes had no intention to linger, however. The “little by-play in the Gulf of Mexico” being over, he headed for Jamaica to land prisoners, resupply, “and proceed on my eastern cruise, against the enemy’s commerce, as originally contemplated.” [11]

Sources:

[1] Chester G. Hearn, Gray Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union’s High Seas Commerce (Camden, ME, 1992), 188.

[2] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 29 vols. (Washington, DC, 1894-1921), Series 1, vol. 19, page 505. Hereafter cited as ORN. All references are to series 1.

[3] Semmes, Memoirs, 337.

[4] ORN 19, 510.

[5] ORN 2, 19.

[6] ORN 19, 510, 507.

[7] ORN 2, 20; ORN 19, 582.

[8] Semmes, Memoirs, 341.

[9] ORN 19, 510.

[10] Ibid., 506.

[11] Semmes, Memoirs, 341.