Les Misérables, the American Civil War, and the Future of Republican Government

Over the past several decades, advances in technology and communications have made the world appear smaller and smaller. Media personalities and politicians tout the benefits and dangers of globalization, as if it was a new thing. Yet over the centuries, vast empires were built featuring conquest, mass migration, and trade spanning thousands of miles of land and sea.

For most of the twentieth century, historians placed little emphasis on the transnational nature of America’s great conflicts, even though French, German, and Polish generals fought for the patriots in the Revolution and foreign-born soldiers and their children accounted for more than forty percent of Civil War Union soldiers.

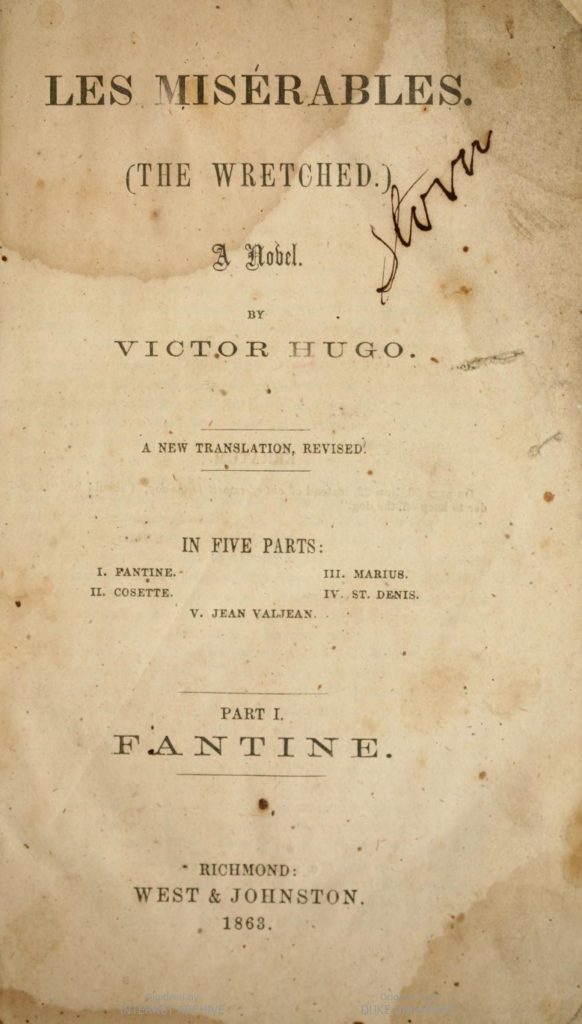

But the contributions of foreign generals and immigrant families to the American war effort, alliances with the French in the Revolution, and British and French neutrality in the Civil War tell only a part of this larger story. The American Civil War was part of an unprecedented international revolution for democratic government, worker rights, and human freedom. The entire world watched to see if our experiment with republican government would survive an internecine crisis that threatened to destroy the United States of America less than a century into its existence. So, it is hardly surprising that French radical and world-renowned novelist Victor Hugo chose to complete a project he had begun more than twenty years previous and publish his magnum opus, Les Misérables, in 1862, in the middle of the American Civil War.

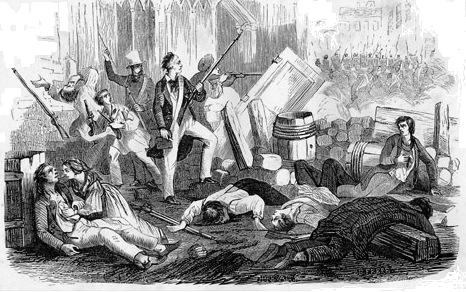

Casual readers often mistake the setting of Hugo’s narrative as the 1848 Springtime of the Peoples, after the dozens of democratic rebellions throughout western Europe; but Hugo set the scene for his novel in 1832, when Paris radicals attempted to establish a second French republic.

Like Americans in 1861, the French of 1832 were a divided people. Ever since their ambitious revolution had devolved into a macabre nightmare, enabling General Napoleon Bonaparte to become dictator and emperor, French democrats yearned for a return to the promise of liberty, equality, and brotherhood. But in the wake of a British-led alliance that defeated Napoleon, France returned to a hereditary monarchy. Sixteen years later, the July 1830 French revolution overthrew Bourbon King Charles X and replaced him with a constitutional monarch – a “citizen king,” as Louis Phillipe styled himself. It was a half-measure that fully satisfied none of the French political factions.

In Hugo’s masterwork, student rebel Enjolras delivers an incendiary speech from atop the barricades. The author tracks his character’s evolution “from the narrow form of dogmatism, and yielding to the broadening effect of human progress,” looking ahead to “the transformation of the Great French Republic into the immense human republic.” [1] The republican revolutionaries of 1832 failed to revive the French Revolution of the previous generation, yet the great U.S. republic persisted across the Atlantic.

Hugo’s own path to becoming a red republican who would create fictional heroes like Enjolras and Marius Pontmercy was uneven and took many years. He came from a wealthy family and first entered politics as a French peer. His earliest writings were decidedly royalist and romantic. He was a mere spectator during the June 1832 Paris rebellion. Following his election as a conservative to the National Assembly of the Second French Republic in 1848, he advocated for abolishment of the death penalty, free public education, and universal suffrage. Despite his liberal sensibilities, he fought to put down Paris workers in the June days revolt later that year. When Louis Napoleon seized power in an 1851 coup, Hugo left France and did not return for twenty years. By 1862, the conservative enigma had become a bourgeois radical.[2]

Hugo understood the political power of popular literature and used Les Misérables to trumpet his favorite cause: the poor and oppressed. He was an outspoken critic of slavery, penning a letter to Virginia’s governor, urging him to spare the life of John Brown. Southern printers, still smarting from Harriett Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin a decade earlier, deleted passages denouncing slavery from Hugo’s narrative.[3]

Hugo did not believe that the American Civil War was about preserving the federal Union in the North or achieving independence in the South. While both sides claimed to embrace republican political values, the Confederate government’s establishment of a republic based on chattel slavery was a direct contradiction of the notions of popular sovereignty and equality espoused by the leaders of the American and French revolutions. “Civil war—what does that mean?” he asked. “Is not all war between men war between brothers? There is no such thing as foreign war or civil war; there is only just and unjust war.”[4]

Like many socialists of the mid-nineteenth century, Hugo believed that societies were constantly evolving toward a more perfect state and that republicanism in the U.S., while far from ideal and stained by human bondage, was still an advanced political system compared to monarchy. In the wake of two failed French republics and an active war in America, Enjolras pleaded in Les Misérables, “Let us offer the protest of corpses, and show that, if the people abandon the republicans, the republicans do not abandon the people.”[5]

Sources:

[1] Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1887), Vol. IV, 89.

[2] Megan Behrent, “The enduring relevance of Victor Hugo,” International Socialist Review, Issue 89, The enduring relevance of Victor Hugo | International Socialist Review (isreview.org).

[3] Mark Jones, “How Les Misérables Became Lee’s Miserables,” Boundary Stones (blog), 13 May, 2019, How Les Misérables Became Lee’s Miserables | Boundary Stones (weta.org).

[4] Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (New York: Kelmscott Society, 1887), Vol. 11, 358.

[5] Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1887), Vol. IV, 77.

1 Response to Les Misérables, the American Civil War, and the Future of Republican Government