The Historian’s Process: Researching for Wreaths Across America

Sarah Bierle and I are busily at work researching Winchester National Cemetery and burials after the battle of New Market for our fundraiser in support of Wreaths Across America. While doing so, I uncovered a story that we won’t be using in the program but is still worth sharing. I want to use this blog post not only to share the information I was able to briefly uncover about this soldier, but also to show a little bit of the research process.

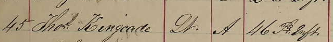

Working through the burial records for Winchester National Cemetery is complicated work. We’ve found that the majority of reinterments for US casualties of the 1864 battle of New Market are unknowns (more to come on that in our program!). So, when I found a record for a “Lieutenant Thomas Kingcade, Company A, 46th Pennsylvania Infantry, Died 1864, Remarks: New Market, Shenandoah County, Virginia,” I knew I found something worth looking into.

His name complicates things, as it is a fairly common name with a variety of spellings. Even though I now know all these records refer to the same man, the original burial record notes it as “Kingcade,” his regimental roster says “Kincade,” his muster roll spells it “Kinkade,”[1] and the 1860 Census spells it as “Kinkead.”[2] Phew! This made it a little more difficult to pin down if records referred to the right individual, and it’s always worth trying out a few other spellings when researching.

There are a few other complications. First, the 46th Pennsylvania was not at the 1864 battle of New Market. By then, they were fighting in Georgia. When I went through the regimental rosters for US troops engaged at New Market, I still could not find anyone with a similar surname to Kincade (I’ve found a wide variance in spelling between these burial records and regimental rosters before) and certainly no Lieutenants that matched the record.

Well, that then leaves an obvious course of action – let’s check the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry’s roster! Here, we find Private (not Lieutenant) Thomas Kincade, who enlisted on September 2, 1861 for three years of service and who “Died May 11, 1862, of wounds received, accidentally, at New Market, Va – buried in National Cemetery, Winchester – lot 1.”[3] This is definitely our guy. Right name, right regiment, specifically mentions New Market as a place of death, and even states he was reburied in the National Cemetery.

Brian Steel Wills recorded numerous accidental deaths in Inglorious Passages: Noncombat Deaths in the American Civil War. Accidental wounds could occur when a soldier or his comrades “demonstrated unusual behavior or proved negligent, careless, or incompetent in their handling of the implements of war,” or it may have simply been an accident partially caused by the weapon.[4] They weren’t particularly uncommon occurrences, don’t fit the normal story of glorious combat death, and are almost more difficult to come to terms with because of the unexpected nature. One of these fates befell Thomas Kincade at New Market in May 1862. George C. Bradley’s 2019 book Surviving Stonewall: Part One of the History of the 46th Pennsylvania Volunteers attributes Kincade’s death to mortal wounding by friendly fire during the regiment’s movement from Luray to New Market the day before.[5]

So, let’s summarize what I’ve pieced together about Thomas Kincade (using the spelling found on his headstone and his regimental records) by consulting various archives and documents. A laborer in Granville, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania living with the Stull family, the 36-year-old joined Company E of the 25th Pennsylvania Infantry for a three-month enlistment. It’s possible he served with the company, the Logan Guards of Mifflin County, prior to the war when it was the local militia. The Company spent their service in the defenses of Washington, DC.

Following the end of the term, Kincade and many others reenlisted into the 46th Pennsylvania Infantry in the late summer of 1861. Assigned to General Nathaniel Banks’ command, the regiment was sent to Harpers Ferry. That winter they crossed the Potomac, venturing into the Shenandoah Valley and squaring off for much of the spring with “Stonewall” Jackson in the 1862 Valley Campaign. Following US victory at the First Battle of Kernstown, Banks pursued south through the Valley. However, Kincade saw very little of this campaign, as he died in early May from his accidental wounds. I found no evidence of a dependent or loved one filing for a pension through his service.

His burial records note original interment in the “Lutheran Grave Yard,” though it’s unclear if this refers to a burial in New Market or a wartime reinterment in a Winchester location where many soldiers were buried. It’s more likely it refers to the New Market burial. In either case, following the war he was moved to the newly formalized Winchester National Cemetery. At some point between 1862 and his reinternment, some details became jumbled. Perhaps the letters on his headboard became faded, or paperwork was miswritten at the time. His rank was recorded as Lieutenant, and perhaps since his records noted New Market, record keepers simply assumed he must have been a casualty of the 1864 battle. [6]

Instead, we find a story of an enlisted man, one who died accidentally during a famous campaign, and who stands as a reminder of the wide range of stories found in National Cemeteries and honored by the efforts of Wreaths Across America.

To make a donation to Emerging Civil War’s fundraiser for Wreaths Across America and participate on the battlefield or virtually, please visit: https://emergingcivilwar.com/ecw_event/2023-wreaths/

[1] Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, U.S., Civil War Muster Rolls, 1860-1869 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

[2] The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M653; Residence Date: 1860; Home in 1860: Granville, Mifflin, Pennsylvania; Roll: M653_1141; Page: 175; Family History Library Film: 805141

[3] Samuel Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 Volume I, (B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869), 1120.

[4] Brian Steel Wills, Inglorious Passages: Noncombat Deaths in the American Civil War (University Press of Kansas, 2017), 135.

[5] George Christman Bradley, Surviving Stonewall: Part One of the History of the 46th Pennsylvania Volunteers (Independently Published, 2019), 284. My thanks to Dave Powell for finding this information for me.

[6] “Record of Deceased United States Soldiers Interred at the National Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia,” 1867. Burial Registers of Military Post and National Cemeteries, compiled ca. 1862–ca. 1960. NAID: 4478151. Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985, Record Group 92. The National Archives in Washington, D.C.

A thoughtful gesture , remembering those who made the ultimate sacrifice to protect the freedoms we enjoy.

No matter how, or where, he died, he gave his life for his country. He should be honored and remembered.

Thank you, Jon! Every cemetery in the country, not just the National Cemeteries, has a story behind the stone.

Nice detective work for an interesting revelation. It seems as if the best Civil War historians are a combination of Sherlock Holmes & Indiana Jones.