“Cut Down in the Bud of his Usefulness” – Edward Ratchford Geary at Wauhatchie

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Evan Portman

In Delmont, Pennsylvania, a small gravestone stands over one of Westmoreland County’s fallen sons. His story, like many others’ in the Delmont Presbyterian Cemetery, is unknown to most passersby. A large, five-pointed star tops the stone, denoting the Twelfth Army Corps, while two crossed cannon barrels denote membership to the artillery. But beyond the gravestone lies a much more compelling story of a son’s sacrifice and a father’s loss.

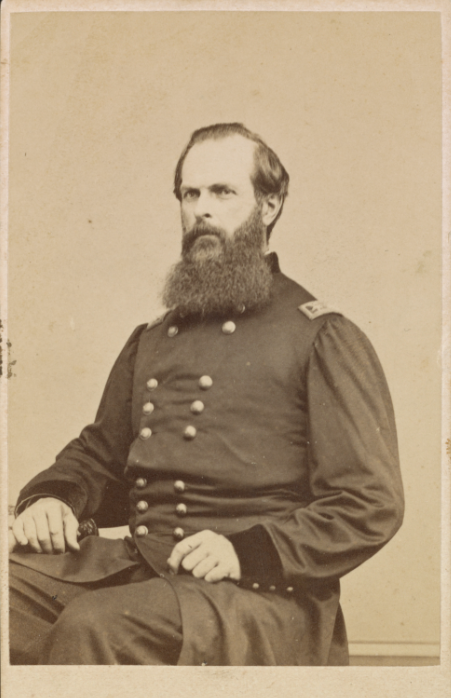

Edward Ratchford Geary, the son of Union Major General John White Geary, enlisted in the Federal army in 1861 at age sixteen. He received a commission as second lieutenant in Independent Battery E, Pennsylvania Light Artillery, also known as Knap’s Battery. The unit saw its first action at the battle of Cedar Mountain, where Edward suffered a minor wound. While his father rose to command the “White Star” division, Edward continued to serve in Knap’s Battery and fought at the battles of Antietam and Chancellorsville. The “white star” division denotes the star as the symbol of the twelfth army corps, and white signifies the second division.[1]

While General Geary’s stature likely influenced his son’s rise through the ranks, the boy’s tenacity in battle earned him a reputation as a hard fighter. At Gettysburg, Lieutenant Geary exposed himself to enemy fire while commanding part of his battery. “I made one very narrow escape from a shell,” he wrote to his stepmother after the battle. “One of the gunners, who saw the flash of one of the rebel guns, hallowed to me to ‘look out, one’s comin,’ and I had just time to get behind a tree before the shell exploded within a foot of where I had been standing.”[2] For his gallantry, Edward earned a promotion to first lieutenant.[3]

By autumn 1863, the Twelfth Corps traveled to the Western Theater to reinforce the Union Army of the Cumberland in Chattanooga. Confederate General Braxton Bragg and the Army of Tennessee had cornered the Union army after its retreat from the battle of Chickamauga. On October 28, the white stars found themselves guarding Wauhatchie Station on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. Bragg sought to destroy Geary’s force and sever Union supply lines. At midnight on October 28, Colonel John Bratton’s South Carolina brigade advanced on Geary’s position. The darkness shrouded Bratton’s advance, and the South Carolinians caught Geary completely off guard. In a rare instance of night fighting, Bratton’s men engaged the white stars in a bloody firefight. Geary’s New York and Pennsylvania men filed into a V formation as the Confederates enveloped their line.[4]

Perched on a small knoll behind Geary’s division, the members of Battery E scrambled to bring their guns to bear on the approaching Confederates. Captain Charles Atwell, the new battery commander, instructed Lieutenant Geary to turn one gun to the right to support the 111th Pennsylvania. The South Carolinians had encroached around the right flank of the Pennsylvanians and threatened the railroad embankment. Hindered by the darkness, the gun crew heedlessly heaved shells to their front, some of which landed among the ranks of the 111th Pennsylvania. Young Geary quickly corrected the error, but moments later a minié ball struck him squarely in the head while sighting his gun. By all accounts, the boy died instantly.[5]

After 3:00 a.m., elements of Major General Oliver Otis Howard’s Eleventh Corps finally arrived to reinforce Geary’s men. Howard arrived just in time; the white stars were beginning to run out of ammunition. With a combined force, the Union troops forced Bratton’s men back by dawn. As the smoke cleared and the sun rose, the Federal line held. But the battle proved costly. Geary’s division suffered 216 casualties in less than three hours.[6] However, one casualty preoccupied the general more than the others. General Howard encountered Geary following the battle and noted that he lacked his “vigorous, strong, hearty and cool-headed” demeanor. “I was surprised to find that as he grasped my hand he trembled with emotion,” wrote Howard. “Without a word he pointed down and I saw that [his] son lay dead at his feet, killed at his father’s side while commanding his battery in this action.” [7]

Years later, Captain George K. Collins of the 149th New York vividly recalled a similar scene. “When the rays of sun came over Lookout Mountain,” he recorded in his regimental history, “they fell with a mellow light upon the tall and portly form of Gen. Geary, standing with bowed head on the summit of the knoll, […] while before him lay the lifeless form of a lieutenant of artillery. Scattered about were cannon, battered and bullet marked caissons and limbers, and many teams of horses dead in harness. And there were many other dead, but none attracted his attention save this one, for he was his son. The men respecting his sorrow stood at a distance in silence while he communed with his grief.” Collins then reflected on the costly suffering of war. “At a moment like this how hollow seems the glory of military honors and how priceless the privileges of a free and united country, which cost so much to attain,” he mused.[8]

Like many Americans of the nineteenth century, John White Geary was no stranger to tragedy. As a teenager, his father’s death compelled him to relinquish his education at Jefferson College and provide for his mother.[9] In the 1850s, Geary witnessed the prolonged illness and eventual death of his first wife, Margaret Ann Logan.[10] Though he remarried five years later and had three more children, Geary encountered family tragedy once again when his son fell at Wauhatchie. This loss, however, plagued him for the rest of the war and his life. On November 2, 1863, four days after the battle, General Geary wrote to his second wife on their wedding anniversary. He confessed his happiness at “the day of our union” contravened by the sorrow for the loss of his son. “Were it not for the almost impenetrable gloom which hangs around me since the death of my beloved son, I would enjoy it,” he wrote. “Poor dear boy, he is gone, cut down in the bud of his usefulness.”[11]

Geary ensured that his son was interred in Delmont next to the grave of his deceased wife. “If we live we will deck his grave with care, and we will make our pilgrimages to it, to weep over the loved, departed one together, and mingle our tears in a common tribute to his memory,” the general resolved.[12] He also politely asked his wife to abstain from any “unnecessary expenditures” so that they could erect a substantial gravestone “to let the world know how much we loved him.”[13] After the war, General Geary made good on his promise to travel to Edward’s final resting place from his home in Harrisburg as frequently as he could. Geary’s own life was cut short when he died of a heart attack at age fifty-three. But Edward’s grave remains, as a silent reminder of the war’s deadly price and the tragedy wrought upon families.

Evan Portman is a fledgling historian from Export, Pennsylvania. He is currently an intern with the American Battlefield Trust as well as a continuing education instructor with the Penn-Trafford Area Recreation Commission. Evan is also a guest contributor of Emerging Civil War and has his own channel on Youtube dedicated to exploring lesser known sites and of the Battle of Gettysburg. A recent graduate of Saint Vincent College, he is currently pursuing a master’s degree in history at Duquesne University.

[1] Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 183-184

[2] Edward R. Geary to Mother, 17 July 1863, Knap’s Battery, GNMP in Pfanz, Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, 183-184.

[3] Edward R. Geary to Mother, 17 July 1863, Knap’s Battery, GNMP in Pfanz, Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, 183-184.

[4] Douglas R. Cubbison, “Midnight Engagement: Geary’s White Star Division at Wauhatchie,” A Journal of the American Civil War, Vol. 3, No. 2, ed. Theodore P. Savas, David A. Woodbury, (United States: Savas Publishing, 2021), 92.

[5] David A. Powell, Battle Above the Clouds: Lifting the Siege of Chattanooga and the Battle of Lookout Mountain, October 16-November 24, 1863 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017), 48.

[6] Cubbison, “Midnight Engagement: Geary’s White Star Division at Wauhatchie,” 96.

[7] Oliver Otis Howard, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard: Volume One, (New York: The Baker and Taylor Company, 1908), 469.

[8] George K. Collins, Memories of the 149th Regt. N.Y. Vol. Inft., 3d Brig., 2d Div., 12th and 20th A.C., (Syracuse, NY: published by author, 1891), 199-200.

[9] Pfanz, Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, 201, 203.

[10] Harry Marlin Tinkcom, John White Geary: Soldier-Statesman, 1819-1873, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1940), 57.

[11] John W. Geary to Mary Church Geary, November 2, 1863, in A Politician Goes to War: The Civil War Letters of John White Geary, ed. William Alan Blair, (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995), 131.

[12] John W. Geary to Mary Church Geary, November 8, 1863, in A Politician Goes to War, 135.

[13] John W. Geary to Mary Church Geary, November 14, 1863, in A Politician Goes to War, 138.

Is Geary in the photo that Gardner took of Knapsack Battery at Antietam and if so where is he in the photo?

A fine article! I enjoy these glimpses into the lives and experiences of individual and little-known CW participants. You’ve restored this promising young man to the historical record – and to our purview as well.

My 5th great grandfather William Parker Guthrie and his second wife lie a few yards away.

William was born in the late 1770s but outlived Lieutenant Geary by 2 years

Evan, great job on this sad story.

Well-done, Evan. Looks like you’ve “fledged”. 🙂

Evan — thanks for very much for the research and photos. Lt. Edward Geary would have been my great-uncle. This account fills in my gaps in my knowledge. I have shared with my three sons. Best Regards, Jim Brooke, Lenox, MA