A Walk Across Payne’s Farm on the 160th Anniversary

The sun is already setting beyond Zoar Church as I start along the trail on the Payne’s Farm battlefield. It was about this same time, 160 years ago, that Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson moved his division from the Racoon Ford Road fifty paces into the woods on my right in preparation for an ambitious “double-envelope” maneuver against the Federal III Corps.

The sun is already setting beyond Zoar Church as I start along the trail on the Payne’s Farm battlefield. It was about this same time, 160 years ago, that Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson moved his division from the Racoon Ford Road fifty paces into the woods on my right in preparation for an ambitious “double-envelope” maneuver against the Federal III Corps.

I’m here, on the anniversary of the battle, to see what I can see and pay my respects.

The church today stands in about the area of the hinge in Johnson’s line. To my front, northwestward, Brig. Gen. George “Maryland” Steuart’s brigade would swing in a right wheel, with their right flank anchored at the hinge and the left flank sweeping clockwise. To my rear, southeastward, the brigades of Brig. Gen James “Stonewall” Walker, LeRoy Stafford, and John “Rum” Jones were to execute a left wheel, with Walker’s left flank anchored at the hinge. Because the three brigades had farther to go—with Jones’s men traveling the farthest—they would not arrive at the point of combat in concert.

The trail winds through the woods toward the intersection of Racoon Ford and Jacob’s Ford, and then parallels Jacob’s Ford Road toward the direction the Federals had come from. The American Battlefield Trust owns the battlefield, and interpretive signs along the trail offer explanations of different aspects of the fight. I don’t bother to stop and read them—not this evening, not with the sun going down. It casts a jaundiced light through the top half of the forest that accentuates the nakedness of the fall-bare trees. Shadows reach from the forest floor to shroud the trees’ bottom halves.

The trail winds through the woods toward the intersection of Racoon Ford and Jacob’s Ford, and then parallels Jacob’s Ford Road toward the direction the Federals had come from. The American Battlefield Trust owns the battlefield, and interpretive signs along the trail offer explanations of different aspects of the fight. I don’t bother to stop and read them—not this evening, not with the sun going down. It casts a jaundiced light through the top half of the forest that accentuates the nakedness of the fall-bare trees. Shadows reach from the forest floor to shroud the trees’ bottom halves.

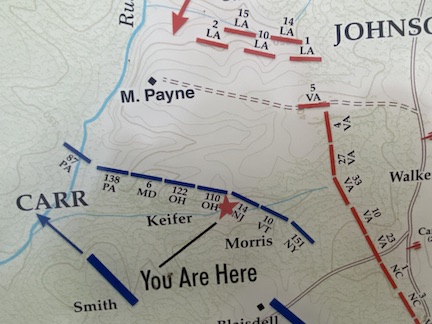

The trail doubles back through the woods, following the advance of Brig. Gen. Joseph Carr’s division into the woods to the east of Jacobs Ford Road. These would be the men who would ultimately face the three-brigade force that made the right jaw of Johnson’s trap. Brigadier General William Morris and Col. Joseph Keifer deployed along the edge of a field, just inside the treeline along a Virginia worm fence. Strands of rusted barbed wire run along parts of the fence today.

The trail doubles back through the woods, following the advance of Brig. Gen. Joseph Carr’s division into the woods to the east of Jacobs Ford Road. These would be the men who would ultimately face the three-brigade force that made the right jaw of Johnson’s trap. Brigadier General William Morris and Col. Joseph Keifer deployed along the edge of a field, just inside the treeline along a Virginia worm fence. Strands of rusted barbed wire run along parts of the fence today.

In fact, this is probably one of the best-known spots of the Payne’s Farm battlefield—if such a thing can be said of a battlefield that’s largely overlooked. We don’t refer to it as “the Forgotten Fall of 1863” for nothing. But here, a small bench sits just inside the treeline, just inside the barbed wire. One of the Trust’s wayside signs explains the action. Trees and foliage frame an open gap that might otherwise be a bay window looking out onto the Payne’s Farm fields. It’s a beautiful view, particularly on a blue-sky, white-cloud day. For me, dusk is settling into the woods around me like tiredness into bones.

My fried Ted Savas, who helped identify this battlefield, calls this spot Keifer’s Ridge. “Use that name whenever you can,” he recently told me. “I gave it that name, and I want it to stick in the literature: ‘Keifer’s Ridge.’” But the “Keifer’s Ridge” is a bit of a misnomer because it only looks like a ridge from the Federal perspective inside the treeline. If you leave the path and step out into the field at this spot—as I do, carefully avoiding the barbed tetanus-on-a-wire—you see the field in a much different way.

Kiefer’s Ridge actually sits partway down a slope. In front of the Federal position, the ground rises to a fair-sized knoll; to the right, the ground drops away into a swale before rising toward a treeline. That treeline and the treeline here by Keifer’s position form two legs of a “V.” The Stonewall Brigade came out of that treeline, pushing toward Morris’s men and, as a result, took flanking fire on the right from Keifer’s men.

But the tumultuousness of the ground offers some surprises, and here we see why preserving battlefields is so important for better understanding the action that took place there. I took a moment to shoot a quick video to show off what I was looking at:

In other words, the right side of Johnson’s double-envelope—the jaw of the trap swinging to the left—could not take full advantage of the topography because they could not all get onto the battlefield at the same time. This allowed Federals to concentrate their fire first on one Confederate brigade, then the next, then the next. As brigades advanced, they got chewed up and fell back, reformed, and tried again—but always in piecemeal fashion.

Imagine if they had been able to get a substantial force out into the field and then taken advantage of the large swale that run down the middle of it. Today, a finger of trees occupies that swale because, as the natural drainage for the field, it’s a partial wetland.

Here’s how the ground looks closer to that position:

From the Payne’s Farm lane—from the area where Stafford’s and Jones’s brigades settled in—you see the field from a much different perspective.

I arrived at this spot at about the time a pair of field pieces from Dement’s 1st Maryland Artillery arrived and began dropping shells into the far treeline. By that time, Keifer’s and Morris’s men were beginning to run out of ammunition (consider what THAT tells you about the ferocity of the fight). Maj. Gen. David Bell Birney’s division had to move into line to relieve the two brigades, bringing ample supplies of ammunition with them.

“After a while, the firing ceased,” one soldier noted, “and everything was as quiet as the grave.”

The full moon, bright as a grapefruit, peaks through the bare tops of the eastern treeline. Soon it will be up. Out here, alone in the middle of a field, surrounded by silent woods, I suddenly feel like I’m in a werewolf movie. It’s probably not the most solemn thing I could be thinking on this 160th anniversary. On the night of the battle, after Johnson’s division slipped away under the cover of darkness, wounded men on the battlefield suffered in the cold, and some froze to death. The detritus of battle littered the ground.

Federals suffered 943 casualties; Confederates suffered 545. Johnson faced 3-to-1 odds—6-to-1 if you include the Federal VI Corps, bottled up behind the III Corps and unable to get into the fight because of the logjam on Jacobs Ford Road—and managed to tie up two-fifths of the Union army at a time when those men were desperately needed elsewhere on the battlefield.

It’s time for me to be elsewhere, time to head back home. It’ll be dinner soon, and my family is waiting. As I walk back to the car, the yellow fades out of the moon as it gets higher in the sky. It’ll be wafer-white by the time I get home, the color of winter.

Great article Chris, thanks! Loved the pictures and videos! Too bad its a forgotten battlefield. This makes me want to walk these fields too.

I hope you get the chance to someday!

Great history a fan from Australia

Chris, I so enjoy your virtual battle walks. They are so vivid. Thanks for celebrating that too often neglected ground.

Thanks, Rosemary. I’m lucky to live in an area where I can go out and walk any number of battlefields pretty much any time I want to. It’s a privilege!

Your skill made your luck, so it’s no privilege. But it’s your honor! Beautiful forgotten field!

Thanks, John. I think in this instance, though, marrying my lovely wife made my luck (and made me lucky!).

Might have to visit there someday, Chris.

Chris I wasn’t aware of this battlefield but your points and placement of the Armies were so methodical, again timing, execution, and perspective of the topography (Nathan Bedford Forrest) that I feel I’ve received a primer. Thank you for detailed and well delivered story, I enjoyed it a lot.

Great article. I’m writing an amateur divisional history on Carr’s division (French’s Pets aka Milroy’s Weary Boys) and your book on the Mine Run Campaign was very helpful.

Payne’s Farm is really an underappreciated battle. Both tactically, and because of its larger strategic impact.

Toured the battle field this afternoon, 3/30/2024. Down by the old barn up against the fence we found large stones in a group and an ancient cedar pine. Did not see indentions but were there graves in this area?

I live in Orange and finally visited the battlefield today. It was an amazing experience, made real by the play-by-plays of the interpretive signage. Even though you’re not far from homes, the battlefield itself is isolated enough that you can imagine that it is 1863 as you stand there.