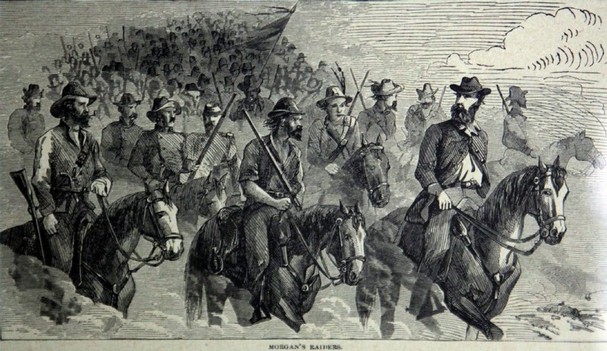

By Hard Fighting: Morgan’s Raiders at Vienna and Vernon

“Rebels are pushing for Lexington, Greensborough or Madison. . . They are pushing with great rapidity, and will cut the Jeffersonville Railroad at Vienna tonight. . . For God’s sake, get up the river, seize all flats and steamboats and guard Warsaw Flats,” read the telegram sent to General Ambrose Burnside on Friday, July 10, 1863 by the citizens of Salem, Indiana.

Upon leaving Salem, Morgan separated his raiders. Keeping the main column intact, they continued to march east toward the town of Vienna by way of Canton and New Philadelphia, while scouting parties were sent north and east toward Seymour, Indiana. On their way to Seymour, the orders read: burn the bridges along the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad. The Confederates’ success in those orders forced the state of Indiana to later reimburse the railroad over $16,000 for damages.

The march to Vienna was fairly uneventful for Morgan’s main column. Arriving in Vienna, the rebels bivouacked for a few hours. In an attempt to thwart pursuing Union troops, Confederate George Ellsworth, an expert telegrapher, sent a false message stating that the Raiders were still in Salem. Those receiving the message realized that something was amiss as the “clicking” pattern of the telegraph instrument was unusual. Despite the false message’s failure, Ellsworth still managed to gather pertinent information. He learned that Hoosiers in southern Indiana had been told to cut down trees and block any roads the raiders would be likely to use. Additionally, he managed to spread some false information on where the rebels were heading which may have aided Morgan by delaying the Union pursuit.

The vast majority of Morgan’s men rested for the night near Vienna. Morgan himself and a small detachment rode 9 miles east to Lexington, Indiana. They stayed at a small lodging house owned by the Meyer family which stood across from the courthouse.

In the early morning hours of July 11, 1863, a small group from the 9th Indiana Legion, led by Colonel Samuel B. Sering, quietly approached Lexington, not aware that John Morgan, himself, lay sleeping in the Meyer home. Sering observed men sleeping on bedrolls in yards throughout the town. The guards at the Meyer house quickly realized something was amiss and raised their guns, intent on defending their leader. Sering and his men tried to escape, realizing a moment too late that they had stumbled upon the raiders. Unfortunately, several of the legion were captured.

By 8:30 a.m., the raiders were once again on the move, heading north toward Deputy, Indiana, in Jefferson County.

Despite the raiders’ reputation of pillaging and plundering, the only accounts of Indiana citizens losing their lives at the hands of the raiders is when they threatened the raiders. That is not to say that the raiders did not take what they wanted or needed; however, for the most part Morgan’s raid through Indiana was mild. There are numerous accounts from both Union and Confederate sources that show the calm demeanor of Morgan. While it may be a more difficult reality to recognize, Morgan and his men were widely known to embody the idea of gentlemanly honor. In comparison to many accounts of northern raids into the Southern states, the treatment of civilians is quite different. The Union, by December of 1863 (6 months after Morgan’s Raid) had fully developed a “hard war” policy, one that deliberately meant to break southern civilian morale. A policy that is not seen from the Confederacy, perhaps only because they are not afforded the opportunity later in the war.

Never-the-less, Morgan held his men to a high standard, and expected them to retain a “gentlemanly” demeanor. When a raider acted in a way unsuitable to Morgan, he would be harshly punished.

A young boy, C. H. Caslin, of Indiana, was asked by his ill mother to fetch water from the cool spring nearby. Upon his arrival, he saw that the rebel raiders were also at the spring. An officer noticing the boy asked if he needed water, when Caslin explained he was fetching water for his mother, the officer ordered his men from the spring immediately, so the young boy could fill his bucket. Furthermore, the raiders often paid for the food and other goods acquired when and where they could with U.S. dollars, as they knew Confederate money would be worthless to those in the North. Simply put the reputation and myth of the raiders may far exceed any of the actual actions of the men.

In Madison, Indiana, later in the afternoon, telegraph operator, Luther Martin, was alone in the office when a suspicious message arrived over the wires, asking how many soldiers were in the town. Unsure of who sent the message and not recognizing the cadence with which the sender “spoke” on the telegraphs keys, Martin quickly replied:

Martin-Madison Ind– We have three government gunboats at the landing and others coming. Many soldiers are already here from Rising Sun, Lawrenceburg, Aurora and Vevay and others are on the way. The Union commander here has altogether 25,000 men ready to meet any attack made by Morgan.

The exchange raised flags for those in Indianapolis, and a warning went out over the lines across Southern Indiana. Martin was attributed with saving Madison from the raiders, and the held a celebration in his honor for the next 45 years on July 12 each year, dubbed Luther Martin Day.

Morgan, not knowing exactly what awaited him in Madison, but erring on the side of caution only made a feint toward the town. Instead, he turned north to Vernon, Indiana. The scouting group that had been sent to Seymour rejoined the main column at Vernon. In the early evening of July 11, as the Rebel Raiders made their way into Vernon, they found Colonel Hugh T. Williams, with nearly 2,000 volunteers and militia ready and willing to fight. Morgan sent a flag of truce demanding the immediate surrender of the town. Williams replied that if Morgan wished to take the town, he “must take it by hard fighting.” Morgan sent a second flag of truce; however, this time the bearer was detained until Brigadier General John Love, arrived from Indianapolis. Love demanded Morgan’s full surrender, but noted that if he meant to fight, requested two hours to evacuate the women and children. Morgan allowed the evacuation but only gave 30 minutes. With the town evacuated, Love expected the battle to begin at any minute. As hours passed, no fight came, discovering by late evening that the raiders had skirted the town and were heading south toward Dupont.

Does anyone out there know the song that came from Morgan’s Ohio raid? My grandmother used to repeat some lines that went “Morgan, Morgan, and his terrible men, are coming down the glen…” She was a great quoter of poetry, but I can’t remember any more about this song.

This grandmother of mine, Elizabeth Tow, grew up in Norway, Iowa, and heard stories from her father Andrew—who had actually been in the pursuit of Morgan’s Raiders.

Thanks for article, and for churning up some old memories. I spent years 9-18 in Madison, Indiana. It was there that I became a Civil War enthusiast. Morgan’s raid was about all our area had to offer for a young student, but it was enough to help get me hooked. I remember my folks taking me to Dupont and seeing several old buildings that stood at the time of the raid. I also remember attending a reenactment in Vernon in the early 1980s, and the following year I actually got to participate in it with a unit willing to take on a 12-year old. Soon, further trips to Tebb’s Bend (another Morgan site) and Perryville in Kentucky sealed the deal.

Douglas Miller–the lines you quote are from a poem titled “Kentucky Belle” written by Constance Fenimore Woolson. The poem can be found on-line.