Book Review: Michigan’s Company K: Anishinaabe Soldiers, Citizenship, and the Civil War

Michigan’s Company K: Anishinaabe Soldiers, Citizenship, and the Civil War. Michelle K. Cassidy. East Lansing: MI, Michigan State University Press, 2023. Softcover, 276 pp. $44.95.

Michigan’s Company K: Anishinaabe Soldiers, Citizenship, and the Civil War. Michelle K. Cassidy. East Lansing: MI, Michigan State University Press, 2023. Softcover, 276 pp. $44.95.

Reviewed by Gregory A. Mertz

During the battle of the Wilderness, Confederate soldiers encountered and pushed back a line of Federal sharpshooters. In their haste to withdraw, the Federals left behind some personal belongings that were seized by the Confederates. This otherwise lackluster incident had a unique element to it: the Confederates reported that the spoils they had confiscated included “copies of the Bible in the Ojibwa language.” (13)

Confederates had encountered Company K, of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters – 138 indigenous soldiers known as “the Indian Company.” Besides the Ojibwe soldiers who lost their Bibles, Odawaag and Boodewaadamiig people—who all referred to themselves as Anishinaabeg or “original people”—comprised what is believed to be the largest unit of indigenous people to serve east of the Mississippi River for the Federal army during the war.

Michelle K. Cassidy recognized that these lost Bibles, as well as the service of their owners in the Federal army, were symbolic of the struggles of the Anishinaabeg to become recognized as citizens of Michigan and the United States. The main theme of the book is that the Anishinaabeg took a variety of steps to gain standing and acceptance as legitimate citizens so they might have more leverage in gaining favorable outcomes in their efforts to own land and to be able to retain access to resources in their ancestral lands in Michigan. The Ojibwe Bibles found in the Wilderness were a link between the early history of the Anishinaabeg under pressure to abandon their land and how their encounters with Christian missionaries played an important role in their pursuit to preserve some semblance of their way of life.

The strength of Michigan’s Co. K is the context it provides for understanding the challenges faced by the Anishinaabe people in the generations just before, during and just after the Civil War. Efforts to improve the relations between the Anishinaabeg and the government were likely motivating factors for many of their actions. Citizenship and voting rights of indigenous people were often predicated upon them being “civilized Indians” although the term had no precise definition and it was not clear just how that status could be achieved. The book explores the ways in which the Anishinaabeg sought to be recognized as “civilized” by engaging with the Christian religion and the English language; attempting to emulate the education and land use of the white settlers; and following accepted practices of citizenship like paying taxes and serving in the army. The Anishinaabeg made earnest attempts to follow governmental requirements, within the parameters of their culture, values, and points of view.

The Bibles lost in the Wilderness is a tangible reminder of the interaction between the Anishinaabeg and Christian missionaries. The Anishinaabeg welcomed the schools that Christian missionaries brought. By obtaining an education, the Anishinaabeg felt they were not only taking an important step toward citizenship and demonstrating they were “civilized,” but by learning the English language, they could better negotiate with government officials and become stronger advocates in protecting those things they valued the most.

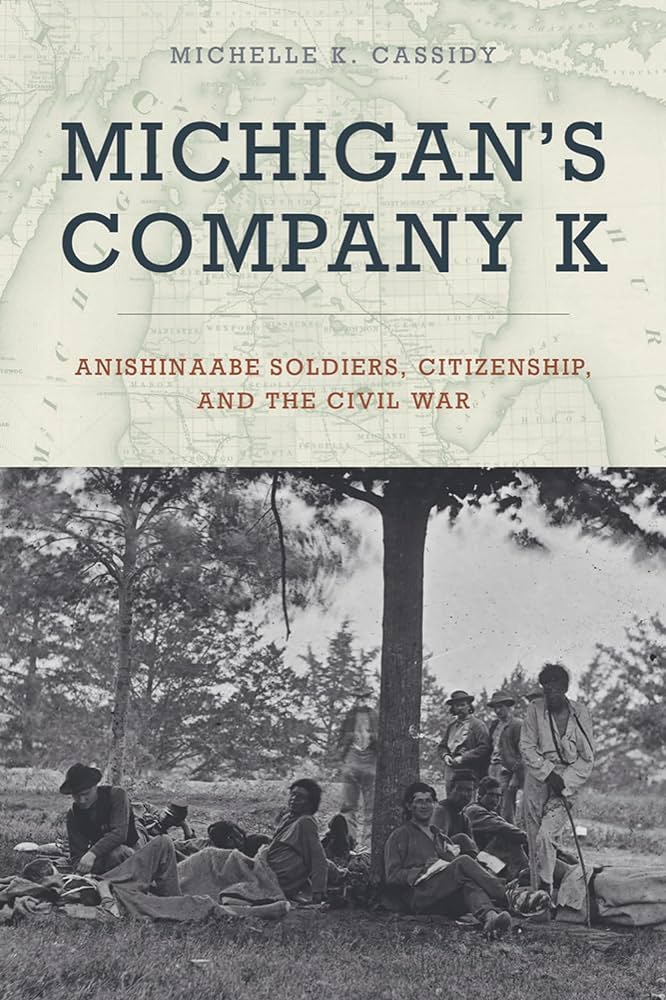

While the chapter on the Civil War is not a tactical presentation and generally does not connect their action to particular battlefield landmarks, the gems in the chapter are found in those individual stories that Cassidy uncovered. Cassidy suggests an individual who may have lost one of the Bibles in the Wilderness, and another who might be in an iconic photograph of “Wounded Indians” taken at a hospital site caring for the wounded from the Wilderness and Spotsylvania battlefields. One of the more dramatic accounts is of a soldier covering the Federal retreat during Petersburg’s Battle of the Crater who was recognized by his superiors with a recommendation that he be nominated for the Medal of Honor.

The final chapters cover the Anishinaabe soldiers and their families in the post-war years seeking pensions and filing for land via such means as the Homestead Act. The pension application process was hampered by language barriers, resistance to strangers asking personal questions, documenting marriage in terms of Anishinaabe customs, and the inability to provide exact dates in a culture that did place importance on such things.

While the service of Anishinaabe soldiers resulted in some officials being sympathetic to their plight, the Anishinaabe struggles continued. A member of one of the non-Indian companies in the same regiment, who admired the service of the members of Company K, perhaps expressed it best when he observed that the Anishinaabe soldier fought “in defense of the country he can scarcely call his own.” (120)

Excellent piece and review here. I would be interested in connecting with scholars who write about native American contributions during the war.