A Celebration of Black History … When Missouri Voted to Emancipate Its Slaves Prior to the Passage of the Thirteenth Amendment

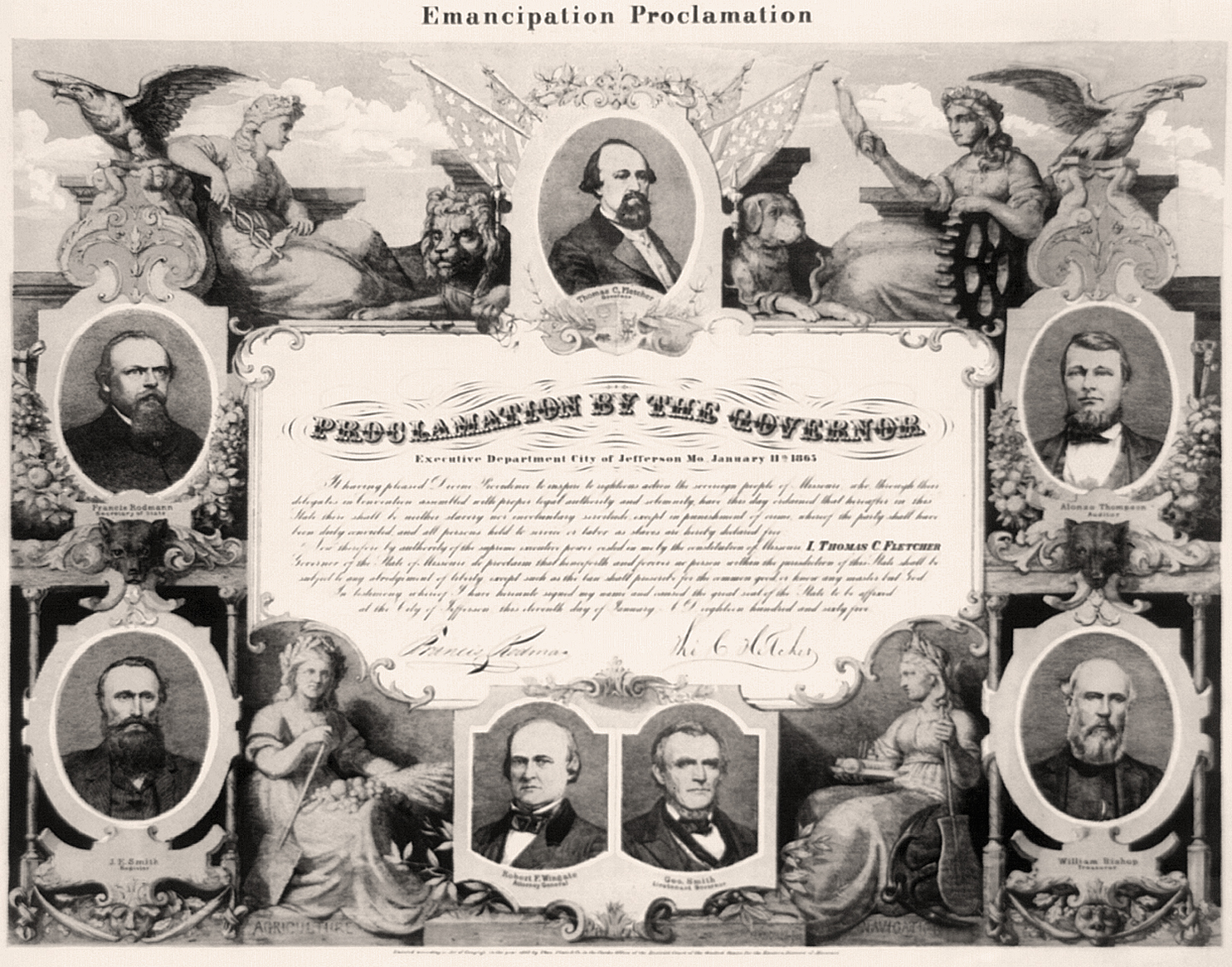

What many do not know, however, is that on January 11, 1865, Missouri’s Constitutional Convention convened in St. Louis, where delegates voted to abolish slavery in Missouri. Only four delegates voted against the proposal. This was three weeks before the U.S. Congress proposed the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, abolishing slavery – and more than eleven months before that amendment would go into effect in December 1865.

Here, in honor of Black History Month, I share an excerpt from my new book, A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri, where I discuss how this emancipation played out in Missouri:

Many slaves, of course, had already escaped during the chaos of the war to one of the four free states bordering Missouri. Some had been stolen away and freed by Jayhawkers and other abolitionists during raids on the homes of Confederate sympathizers. Many more took it upon themselves to disappear during the night, sometimes taking their former master’s horses, mules, or wagons along with them. Some waited until the river froze to cross over. But now, the Emancipation Ordinance clearly stated: “That hereafter in this State there shall be neither Slavery nor involuntary servitude, except in punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, and all persons help to service or labor as slaves, are hereby DECLARED FREE” (2).

Many wondered if a similar ordinance might soon be drafted for the United States. Lincoln, of course, had already issued his Emancipation Proclamation back in January of 1863, freeing “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State … in rebellion against the United States.” However, that proclamation had been limited in its scope and had not abolished slavery in the United States, as so many hoped to see happen.

Something else Lincoln’s proclamation had done, though, had proved essential to the war effort: it opened the door for freed Black men to fight for the Union. Almost 200,000 had answered the call, serving in both the army and the navy. By the end of the war, at least 166 regiments of Black soldiers had fought in approximately 450 battle actions, including the Battle of Nashville described earlier in this chapter, proving instrumental in helping to win the war and freedom for their people (3).

Even before the Emancipation Proclamation, many escaped slaves from both Missouri and Arkansas, having made the journey to free Kansas, found themselves recruited to fight for the Union. There, Jayhawker and Union General James Lane formed the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment in August of 1862 – just one month after the Militia Act of 1862 first allowed Blacks to serve in militias as soldiers and war laborers. Going against the direct orders of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Lane mustered the first Negro regiment to fight in the Civil War, and under the command of Captain James M. Williams, they launched several attacks against guerrilla bands and Confederate forces in Missouri.

Their first Civil War engagement in combat happened just two months later in the Battle of Island Mound in Bates County, Missouri, near the western border. By the fall of 1862, Bates County had become a haven for guerrillas, many of whom were using Hog Island on the Marias-des-Cygnes River as a base for attacking pro-Union families in eastern Kansas. In order to clear out this guerrilla den, 240 soldiers and 12 officers of the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry marched into Bates County on October 27, 1862, and took over the home of some local Southern sympathizers to serve as their headquarters. They named their new base “Fort Africa.”

Over the next couple days, they had some skirmishes with local guerrillas. On October 29, guerrillas “set fire to the tallgrass prairie, forcing the Kansas troops to set a backfire to prevent flames from reaching Fort Africa. Using the smoke as cover, the rebels fired at the troops then withdrew, hoping the Kansas troops would pursue them. A party of eight Black soldiers went to locate the rebel position. Venturing farther from camp than ordered, the troops traveled out of sight behind a low hill known as Island Mound. A party of about 20 men sent to locate the first squad joined them and moved farther away from camp. The rebels had successfully lured the Kansas troops into a trap” (4).

When about 130 rebel horsemen emerged from the nearby woods, the Black detachment retreated toward Island Mound but were caught before they could reach shelter. Hand-to-hand combat ensued, the rebels carrying “shotguns, pistols and sabers and outnumber[ing] the Black troops 6 to 1 … [and] the Black soldiers [fighting] back fiercely, using their bayonets and rifle butts” (5). When reinforcements arrived from Fort Africa, the rebels retreated – leaving behind supplies and livestock.

The Black soldiers who fought in the Battle of Island Mound earned praise from both sides. Union Lt. R. Hinton told the Daily Conservative in Leavenworth, Kansas, that the campaign “proved that negroes are splendid soldiers,” and Southern Rebel Bill Turman was quoted in the New York Times saying they “fought like tigers” (6).

Ultimately, the bravery and skill they showed in the battle “refuted claims that Black soldiers lacked the courage or ability to engage in combat. It also paved the way for additional African American regiments…. On Jan. 13, 1863, less than two weeks after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry became the fifth African American regiment mustered into Federal service – three months after they won their first battle” (7).

When urging Lincoln to allow Black men to join the war effort, former slave and outspoken abolitionist Frederick Douglas reportedly told him, “We are striking the rebels with our soft white hand, when we should be striking them with the iron hand of the black man which we keep chained behind us” (8). Lincoln finally relented and issued a call to raise Black regiments. Massachusetts Governor John Andrew responded by forming the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He appointed Robert Gould Shaw, the son of prominent abolitionists, to lead them.

Douglass lent his voice to the cause of recruitment, both in speeches and in newspapers, and continued to advise Lincoln on getting more Black men involved in the war effort. According to Douglass, by joining in this fight, Black men could gain self-respect and self-defense skills, prove their worthiness, and win their citizenship rights (9). Two of Douglass’s own sons enlisted. There were, in fact, so many volunteers that they formed a second Black regiment: the 55th Massachusetts.

Though initially relegated to manual labor, the soldiers of the 54th Regiment eventually proved their abilities and heroism when they led the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina in July 1863: “Though clearly a military defeat, the 54th Regiment’s heroic assault on Battery Wagner proved both a powerful political and symbolic victory. Through their actions, the 54th helped convince a skeptical public and military that Black men could and would fight bravely…. The heroic efforts of the 54th Regiment inspired the nation to begin mass recruitment and mobilization of Black soldiers. The 54th paved the way for more than 180,000 Black men joining the United States forces, which ultimately helped turn the tide of the war” (10).

In the letters I include in my book, both James Calaway Hale and Benjamin Petree mention ways in which former slaves were helping the Union army – including cooking, cleaning, doing laundry, and helping to report on Rebel movements. They never mention their thoughts on slavery, but I like to imagine that they were happy to learn their home state of Missouri had made the decision to act on its own to emancipate its slaves.

By contrast, neighboring Kentucky continued to oppose efforts to abolish slavery, voting on February 24, 1865 to reject the Thirteenth Amendment. Many today celebrate Juneteenth as the day the last slaves being freed, thinking this happened on June 19, 1865, in Texas. However, “the enslaved men, women and children of Kentucky were the last to finally taste freedom – over six months after June 19th,” when the Thirteenth Amendment was finally ratified. [12] Kentucky did not officially adopt the Thirteenth Amendment until 1976.

Sources:

- “Missouri Emancipation Proclamation, January 1865, zoomable image,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/39533.

- “Missouri Digital Heritage: African American Initiative: 1865 Constitution.” Missouri Secretary of State, https://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/resources/africanamerican/guide/image005c.

- Henderson, Steward. “The Role of the USCT in the Civil War.” American Battlefield Trust, 27 October 2020, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/role-usct-civil-war.

- “Historic Site History at Battle of Island Mound State Historic Site.” Missouri State Parks, https://mostateparks.com/page/60129/historic-site-history.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Confronting a President: Douglass and Lincoln – Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.” National Park Service, 24 July 2021, https://www.nps.gov/frdo/learn/historyculture/confronting-a-president-douglass-and-lincoln.htm.

- Evans, Farrell. Why Frederick Douglass Wanted Black Men to Fight in the Civil War, 22 November 2022, https://www.history.com/news/frederick-douglass-civil-war-black-recruitment.

- Adams, Virginia M. “54th Massachusetts Regiment (U.S.).” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/54th-massachusetts-regiment.htm.

- Photo by Tonya McQuade, Boston Common, July 2019. As stated on the NPS Website: “Augustus Saint-Gauden’s high-relief bronze monument on Boston Common in downtown Boston commemorates the service and sacrifice of Colonel Shaw and the soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts. Dedicated in 1897, the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Massachusetts Memorial is now part of Boston African American National Historic Site. Commissioned by a group of private citizens, Saint-Gaudens first envisioned a lone equestrian statue of Colonel Shaw. Shaw’s family encouraged Saint-Gaudens to take a different approach, and the resulting work commemorated not only the regiment’s famed colonel but also the Black soldiers he commanded, a revolutionary concept for the time period.” Adams, Virginia M. “54th Massachusetts Regiment.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/54th-massachusetts-regiment.htm.

- “Juneteenth: Why Kentucky was last to free enslaved people, not Texas.” The Courier-Journal, 16 June 2022, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/opinion/2022/06/16/juneteenth-why-kentucky-last-free-enslaved-people-not-texas/7610522001/.

Of course many of those who would have voted against the resolution were either in Union prison camps, jail, or on their way home from service in the Confederate Army. The abolitionist made hay while the disenfranchised whites were away. As they say, the law of unintended consequences, like that bigger one, the state of West Virginia.