Tennessee Johnson Reel vs. Real

ECW welcomes back guest author Tom Elmore

No United States president has been depicted more in television and movies than Abraham Lincoln. Since Leopold Wharton first portrayed him in 1910’s Abraham Lincoln’s Clemency, the 16th President has appeared in 137 productions. By comparison, the man who succeeded him, Andrew Johnson, has only been the subject of one film biography, 1942’s Tennessee Johnson produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). [1]

With the working title Andrew Johnson, The Man on America’s Conscience, MGM chose one of Hollywood’s best directors to work on the film, William Dieterl, a 1937 Oscar nominee for Best Director for The Life of Emile Zola, which won Best Picture. He also directed such notable films as The Story of Louis Pasteur, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and The Devil and Daniel Webster.[2]

To head the cast, MGM chose Van Heflin, who had just won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his performance in Johnny Eager. The 34-year-old Heflin was about twenty-five years younger than Johnson was when he was president, but thanks to the talents of Jack Dawn, who was also the make-up supervisor on the Wizard of Oz, Heflin would bear a passing resemblance to the 17th President.[3]

Playing Johnson’s political foe, Representative Thaddeus Stevens (R-Pa.), was Hollywood legend Lionel Barrymore. He was excited about the part as it was a change from the type of roles he had been recently playing, and reportedly enjoyed it very much.[4]

Others in the cast included Ruth Hussey, who had received an Oscar nomination in 1940 for The Philadelphia Story, as Johnson’s wife, Eliza. Also in the cast was Marjorie Mann, who later achieved film immortality as Ma Kettle in the Ma and Pa Kettle film series.

Given the careful thought that MGM put into selecting the director, cast, and make-up artist, one would think that they would put the same care into the script but the studio did not.

The resulting screenplay shows that the writers did not dig deep into the history of the people and events surrounding the Johnson administration. Even MGM acknowledged this in the opening credits by stating:

The form of our medium compels certain dramatic liberties, but the principle facts of Johnson’s own life are based on history.

Or was it? Consider the following:

Reel: The opening scene shows Johnson, as a desperate, dirty young man in tattered clothes with a shackle and chain around an ankle. It is revealed that he is an escapee from an apprenticeship. Later he shows the shackle to a group of Radical Republicans.

Real: Johnson fled his apprenticeship with a group of others at age 15, for which a $10 reward ($228 today) was offered for his capture. There is no record of him ever wearing shackles.[5]

Reel: His wife taught him to read and write

Real: He was already literate when he married her.[6]

Reel: All southern U.S. senators quit at the same time and called Jefferson Davis their leader.

Real: The first seven states seceded over the course of 62 days from December 1860 to February 1861. Four others left between April and June 1861. There was never a mass exodus of Southern senators as depicted in the film.

While the film does use quotes from Davis’s actual farewell speech to the Senate, delivered on January 21, 1861. However, only five states had left the Union by that date. Also, Davis did not want a political office in the new Confederacy, but a military one, and not every Southern politician wanted Davis to be their leader.[7]

Reel: Southern senators call Johnson a traitor to the South and the Confederacy because he does not join the walkout.

Real: Given that the Confederacy was founded three weeks after Davis’s speech and that Tennessee left the Union on June 8, 1861, more than five months later, one cannot say that Johnson was a traitor to the south or the Confederacy that day.

Reel: Johnson offers his services to Lincoln after the walkout.

Real: Johnson continued to serve in the Senate until he was named military governor of Tennessee on March 4, 1862.

Reel: Barrymore’s Stevens is shown as a wheel-chair bound invalid.

Real: Sen. Charles Sumner (R-Ma.) was wheel-chair bound. Stevens was not. It seems like someone got the two politicians, who shared similar views and were political allies, mixed up.

Reel: Johnson is drunk at his vice presidential inauguration, but Lincoln laughs it off. It is implied that Johnson does not drink.

Real: Though some have claimed that this was the only time he drank in his life, the generally accepted view is that the man liked his whiskey. How much he liked it is subject to debate.

Lincoln was visibly upset by Johnson’s inebriation, but defended his vice president by telling someone that “Andy ain’t a drunkard.” Mary Todd Lincoln, on the other hand was mortified. Nonetheless, the only time Lincoln and Johnson spoke to each other after the inauguration was April 14, 1865, the day Lincoln was killed.[8]

Reel: Johnson says he does not know who John Wilkes Booth is.

Real: Even before he murdered Lincoln, John Wilkes Booth was a very well-known actor. It is highly unlikely that Johnson would have never heard of him.

Reel: Congressman Stevens tells Johnson that he makes “terrible speeches.”

Real: Johnson was recognized as a good speech maker by both his political friends and foes.[9]

Reel: An unnamed, frighten, cabinet secretary rushes to Stevens’s office and says that Johnson has fired him. Stevens tells him not to worry and to barricade himself in his office.

Real: The “Secretary” was based on Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Though Johnson had originally asked Stanton to continue in his post, the two men had a falling out over Reconstruction policies. To protect the secretary, whose views on Reconstruction were similar to those of the Radical Republicans, Congress passed in 1867, over Johnson’s veto, the Tenure of Office Act, which gave Congress the authority to approve the firing of cabinet members by the president. Johnson’s decision to fire Stanton led to the president’s impeachment.[10]

Upon his “firing” Stanton did not rush to anyone’s office, though he defiantly lived in his War Department office, where Radical Republicans in Congress sent messages urging him to stay there. Stanton moved out after Johnson’s acquittal after submitting his resignation.[11]

Reel: Johnson spoke on his own behalf before the Senate, saving his presidency.

Real: Though Johnson did want to address the Senate, his lawyers held him back for legitimate fears that he would do more harm than good.[12]

Reel: The deciding vote that saved Johnson’s presidency was cast by a Sen. Huyler who had fainted during the vote.

Real: There was no Sen. Huyler. Senator Edmund Ross (R-Kansas), who did not faint, cast the deciding vote.

A few other errors include the fact that instead of calling it “The Executive Mansion,” 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is called the White House, a designation it did not have until 1901. Also there are 48 star flags seen in the movie.

The credits for the screenplay do not offer any clues as to who is to blame for the historical inaccuracies. The “original story” is credited to Milton Gunzburg and Alvin Meyers, with the script by John L. Balderson and Wells Root.

Gunzburg is credited with only five screenplays, of which Tennessee Johnson was his third. He is better known for his pioneering work in 3-D cinematography in the 1950s. Little is known about Meyers, whose only film credit is this one, suggesting that “Meyers” may have been someone’s nom de plume.[13]

Arguably, Balderson was the best of the four. He was a two-time Oscar nominee (The Lives of a Bengal Lancer in 1936 and Gaslight in 1945), and is remembered today for his contributions on the scripts on classic Universal horror films, including Dracula and the Bride of Frankenstein. He was also one of many who worked on the script of Gone With the Wind. Tennessee Johnson would be one of his last projects.[14]

Root was a veteran screenwriter who started his career in 1928 and wrote scripts in both films and television until the 1960s. Except for the 1937 version of The Prisoner of Zenda, none of his screen credits are notable.[15]

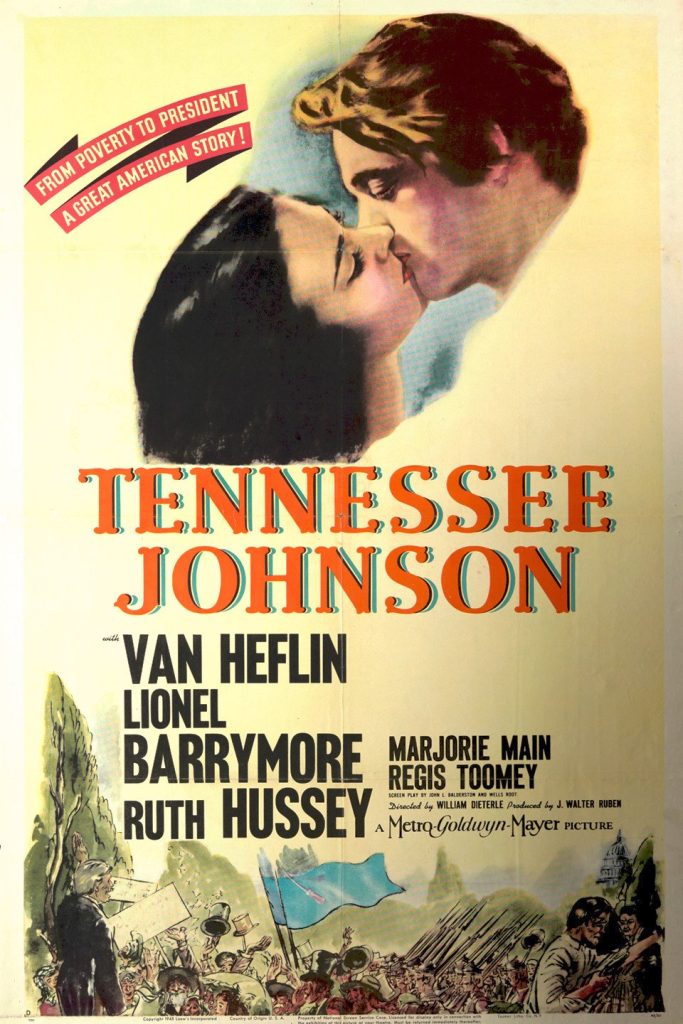

Despite the historical liberties, the trailer for the film, titled A Two Minute Quiz, tried to pass itself off as a history exam, asking the audience if they knew the name and the life of Andrew Johnson. The trailer went on to say, “MGM has fashioned a brave drama of a proud young America valiantly fighting for unity.” However, the film’s poster, which featured Heflin kissing Hussey, could suggest that the film was a love story.

The film was released on December 3, 1942. Even before its premiere, it faced controversy. The United States Office of War Information (OWI), upon looking at a rough cut of the film, expressed concerns about how it portrayed views on slavery, emancipation, and African-Americans, which in turn could affect the war-time morale of African-Americans. They also complained that the film showed Johnson, whom Frederick Douglass called “no friend of our race” too favorably and Stevens, one of the biggest abolitionists of his day, unfavorably. Consequently MGM spent $250,000 on reshoots to address these issues. The final cost for the 102-minute film was $1,042,000, about $18.7 million today.[16]

Despite the re-shoots, the film was still protested by the NAACP. A number of actors, including Zero Mostel and Vincent Price, unsuccessfully petitioned the OWI to destroy the film in the name of national unity.[17] Despite the controversy, the film got decent reviews. Van Heflin’s performance was praised by critics. Despite this, it made only $684,000 (about $12.3 million today) a loss of $637,000 ($11.4 million today).[18]

While it is easy to dismiss Tennessee Johnson as a good example of how not to do a bio-pic, it was also a wasted opportunity to tell the story of one of America’s most controversial presidents and bring to light an often overlooked part of U.S. history.

Tennessee Johnson occasionally shows up on the Turner Classic Movies channel and is available on DVD and Blu-Ray.

[1] Abraham Lincoln “Character” found in the Internet Movie Data Base (IMDB) www.IMBD. Com, keyword “Abraham Lincoln/character.”

[2] Unless otherwise noted all references to the production, cast and crew of Tennessee Johnson comes from the IMDB website.

[3] IMBD

[4] He is also the great-uncle of actress and talk-show host, Drew Barrymore.

[5] Trefousse, Hans L., Andrew Johnson-A Biography. 1989. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, Pg. 23 All modern values from www.measuringworth.com.

[6] Ibid, Pg. 29

[7] Jefferson Davis’ Farewell Address-January 21, 1861. The Papers of Jefferson Davis, Rice University, https://jeffersondavis.rice.edu.

[8] Trefousse, Pgs.191, 192

[9] Gordon-Reed, Annette, Andrew Johnson. 2011. Times Books, New York, Pg.80

[10] Trefousee, Pgs. 276-277, 295.

[11] Marvel, William, Lincoln’s Autocrat. 2015. UNC Press Books, Chapel Hill, N.C., Pgs. 442-450

[12] Gordon-Reed, Pg.80

[13] IMDB

[14] IMDB As a journalist, Balderson covered the opening of the tomb of King Tutankhamen in 1923. Nine years later he wrote the script for The Mummy.

[15] IMDB.

[16] Douglas, Fredrick, The Life and Times of Fredrick Douglas. 1882. Park Publishing Company, Hartford CT. Pg. 442. Tennessee Johnson, Turner Classic Movies, www.tcm.com, “The Hollywood Ten(nessean),” Bill Kauffman, Chronicles, October 1998, Pgs. 39-40. Budget figures from The Eddie Mannix Leger, Los Angeles. Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

[17] Brown, Jared, Zero Mostel: A Biography. 1989. Atheneum, New York. Pgs. 35-36, Kauffman.

[18] The Eddie Mannix Leger.

Excellent article. I loved the comparisons between movie and real life. One thing I wanted to note, though:

Lionel Barrymore was also wheel-chair bound in “It’s a Wonderful Life” in 1946. I think that’s how he was in real life by this point in his career, so if anyone wanted him in their movies they had to work that aspect into the script.

Great article!

Will have to find this film.

Johnson wasn’t actually a drunk but was drunk at his inauguration because he was ailing and drank to ease his suffering. He had been in pain for weeks. There are a lot of quotes from cabinet members, congressmen, and government officials that Johnson was always in control of his faculties although he continued to have health issues while President.

Johnson’s son and secretary was an alcoholic apparently.

Stories like this remind me I need to spend more time in the study of the post-war era, as many commentators point to that period as helpful context for today’s frictions.