It Didn’t End with Lee’s Surrender at Appomattox: A Look at the Surrenders of Gen. Joseph Johnston and Gen. Kirby Smith on April 26 and May 26, 1865 – Part I

April is a month marked by significant dates in Civil War history – most significantly, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Many remember that date as the “end” of the Civil War. However, more surrenders were needed for the war to truly be brought to an end.

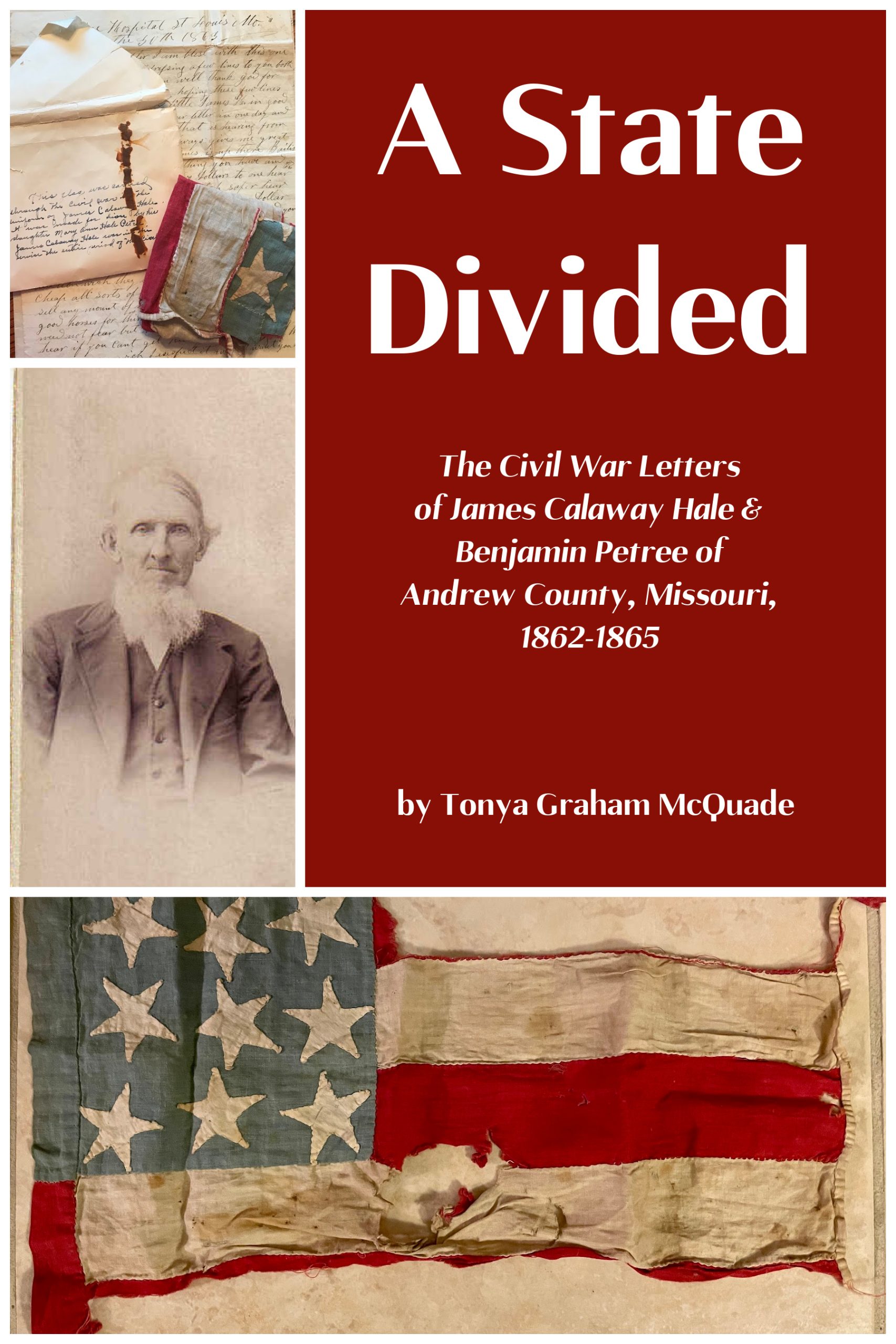

In my recently published book A State Divided: The Civil War Letters of James Callaway Hale and Benjamin Petree of Andrew County, Missouri, both Hale and Petree write about the final days of the war. They were also both in places that were still at war after April 9: Petree was serving in Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s army, and Hale was serving at Benton Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri. In the next two posts, I will discuss the surrenders that finally brought the war to an end for each of them.

Excerpts from A State Divided, Chapter 13:

As Benjamin Petree camped with his regiment outside Raleigh in North Carolina, the news arrived that Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee – having found his army surrounded with no chance of escape – had surrendered his 28,000 troops to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia on April 9….

Though many in the Union considered Confederates traitors, believing them “personally responsible for this tremendous loss of lives and property” and wanting to see them punished severely, not all Northerners felt this way. Grant’s terms of surrender and the Lincoln administration’s actions were focused on “healing the country, rather than vengeance…. There would be no mass imprisonments or executions, no parading of defeated enemies through Northern streets. Lincoln’s priority – shared by Grant – was ‘to bind up the nation’s wounds’ and unite the country together again as a functioning democracy under the Constitution; extended retribution against the former Confederates would only slow down the process” (1).

In his second inaugural address on March 4, 1865, Lincoln had urged, “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations” (2).

With Lincoln’s words in mind, Grant met with Lee to discuss the terms of surrender. Lee agreed that his soldiers would surrender their arms, return home, and agree not to take up arms against the U.S. government again. Grant agreed to allow Confederates who owned their own horses to keep them so that they could tend their farms and plant spring crops. After reaching this agreement, Grant reportedly told his officers, “The war is over. The Rebels are our countrymen again” (3).

Petree and Hale – along with many other soldiers – must have wondered if it could really be that simple. Could brothers who had taken up arms against brothers, cousins who had fought against cousins, simply lay down their arms and reunite around the family dinner table?

Would former neighbors who had supported the Rebels, jeered at Union supporters, hung Confederate flags from their homes, rooted for the guerrillas who had killed some of their neighbors’ families and friends, and later fled Andrew County to avoid Union attacks, simply return to their homes – and everything go back to normal?

Should the outlaw guerrilla bands, who had brutally killed, tortured, maimed, and raped so many fellow Missourians, burned bridges and destroyed railroads across the state, ransacked businesses and burned towns, and often acted on their own accord apart from military supervision or command, also simply be forgiven and allowed to resume their daily lives?

Whatever the future might bring, the war was finally – thankfully – coming to an end. There were still reports of minor skirmishes coming in, but those, too, would soon be brought under control. President Lincoln’s second term was underway, and many hoped his second term would be a substantially happier and much more peaceful one. That happiness soon took a quick turn with the news that President Lincoln had been shot….

Two weeks later, everyone felt a great sense of relief at reports that John Wilkes Booth had been captured and killed…. On that same day, April 26, Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston surrendered his Army of the Tennessee – the largest Confederate force still in existence – to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in Durham Station, North Carolina. Johnston also surrendered other forces under his command in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida – altogether surrendering more than 89,000 soldiers.

The days leading up to Johnston’s surrender must have kept Petree and his fellow soldiers on edge. From April 10-14, they had advanced on Raleigh, then occupied the city, having discovered that Johnston and his army had withdrawn to Goldsboro, North Carolina, before they arrived. Soon after this, the news of Lincoln’s assassination and the search for Booth filtered in, and angry, vengeful mobs of soldiers caused destruction throughout Raleigh. Johnston’s official surrender came about a full twelve days after he first initiated capitulation talks. Even more, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his Cabinet were still on the run, having fled from Richmond before Lee’s surrender.

Johnston had, in fact, met with Davis, as well as with Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, on April 13 in Greensboro and learned that Davis was still bent on continuing to fight. Johnston “tried to dissuade Davis from his plan for renewed combat by arguing that the Union forces outnumbered the Confederates by eighteen to one, the Confederacy lacked the money, credit, and factories to purchase or produce more arms, and fighting would only further devastate the South without significantly harming the enemy” (4). Johnston thought the best course of action now was to secure the best terms possible. Beauregard agreed. Davis finally consented to open communications with Sherman – though he “still believed that victory was achievable despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary” (5) and left Greensboro without notifying Johnston of his departure….

Sherman and Johnston met on April 17 at the farm of James Bennett in Durham’s Station, and Sherman offered Johnston the same terms granted to Lee. However, Johnston pushed for additional political concessions, offering to “negotiate the terms of the surrender of all the remaining armies in exchange for amnesty for Davis and his cabinet” (6). Sherman initially rejected Johnston’s suggestion, and the two agreed to meet again the following day, when they finally reached an agreement: “Under this agreement, hostilities would be suspended pending approval of the agreement, Confederate arms were to be deposited in the respective state arsenals and could only be used within that state, and officers and men had to sign an agreement to cease all hostilities of war. Additionally, the president of the United States would recognize all southern state governments as long as their officers and legislators took an oath of allegiance, and the federal court system would be reestablished in the southern states. The president would also guarantee the personal, political, and property rights of the southern people and grant legal amnesty to all southerners, which implicitly included Davis and his cabinet” (7).

While Sherman waited for Federal authorities in Washington to approve the agreed-upon terms, he had his men set to work rebuilding railroads and telegraph lines. He also positioned his army at key points around Johnston’s army in case the deal should fall through. While Johnston waited, he watched his army grow increasingly demoralized, lose its discipline, turn to thievery, and desert by the thousands – many frustrated with the lack of adequate provisions and fearful they might become prisoners of war.

Despite Sherman’s high hopes, Grant himself showed up in Raleigh on April 24 to relieve Sherman of command and tell him that Federal authorities had rejected his terms, which were viewed as too generous to the South – especially with Northerners reeling from Lincoln’s assassination and many clamoring to show the South no mercy. Not only were the terms rejected, but Grant told Sherman he was being given 48 hours to obtain Johnston’s surrender on the same terms offered to Lee, or Union troops were to resume hostilities, either by attacking Johnston and his army or following if they should retreat….

With their temporary truce on the line, Sherman and Johnston met again, but had difficulty agreeing on terms. They agreed that Johnston’s soldiers would cease all hostilities, assemble at Greensboro, deposit their military supplies, and return home; but Johnston worried his troops would turn to marauding and thievery without adequate provisions made for their transportation home. No such provisions were made for Lee’s army, and “the countryside became infested with gangs of pillaging veterans” (8).

The problem was ultimately resolved with the help of Maj. Gen. John Schofield, Sherman’s second-in-command. Since Schofield was “already assigned to become commander of the district after surrender, [he suggested] a simple, ingenious solution: a second document, unconnected to the surrender terms, spelling out the logistical details for feeding and transporting the surrendered troops” (9). Schofield prepared supplemental terms: “Johnston’s army and his naval force would cease all hostilities, each brigade could keep 1/7 of its small arms and soldiers would deposit their arms at their respective state capitols, all officers and men were to be paroled and take an oath to not take up arms against the United States, their paroles would be signed by their immediate commanders, soldiers could retain their horses and other private property, and the Union army would provide field, rail and water transportation home to paroled men. Separate from this agreement, Sherman also promised 250,000 rations to the newly paroled troops,” as well as flour and corn meal distributed to civilians, earning Johnston’s deep gratitude (10).

One has to wonder what the average soldier like Benjamin Petree, camped in the field, was thinking as these negotiations dragged on. The troops had experienced emotional extremes in the past couple weeks, first with the joyous news of Lee’s surrender, then a week later, the tragic news of Lincoln’s assassination. What did Benjamin think when he learned Sherman’s initial terms had been rejected? That Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck had directed other Union commanders to no longer obey Sherman’s orders? Was this even something that average soldiers knew about?

Did Benjamin see Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s New York Times article denouncing his commander, with whom he had marched so many miles through the Carolinas? Did he, like many of Sherman’s soldiers, “fervently [defend] their commander and [come] close to insurrection” upon hearing these slanderous accusations (20)? How did he feel upon learning the army might be forced to resume hostilities against Johnston’s army? Or when he finally learned that the revised terms had been accepted? What did he think of the decision to let Confederate soldiers – and officers as well – simply lay down their weapons and go home, without further reprisal?

I hope you’ve enjoyed this excerpt from A State Divided, which is available for purchase on Amazon if you would like to read more. In Part II, I will look at the surrender one month later, on May 26, of Gen. Kirby Smith, commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, which included Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory, and the Indian Territory.

Endnotes:

- Rubenstein, Harry. “The Gentleman’s Agreement That Ended the Civil War.” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/gentlemans-agreement-ended-civil-war-180954810/.

- “Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address – Lincoln Memorial.” National Park Service, 14 October 2020, https://www.nps.gov/linc/learn/historyculture/lincoln-second-inaugural.htm.

- Rubenstein, Harry. “The Gentleman’s Agreement That Ended the Civil War.” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/gentlemans-agreement-ended-civil-war-180954810/.

- “Bennett Place Surrender.” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/bennett-place-surrender.

- “Bennett Place Surrender.” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/bennett-place-surrender.

- Gerard, Philip, et al. “One Nation, Again After Johnston’s Surrender | Our State.” Our State Magazine, 7 April 2015, https://www.ourstate.com/johnstons-surrender/.

- “Bennett Place Surrender.” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/bennett-place-surrender.

- Shaeffer, Mathew. “Confederate Surrender at Bennett’s Place (April 17-26, 1865).” North Carolina History Project, https://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/confederate-surrender-at-bennetts-place-april-17-26-1865/.

thanks Tonya … i enjoyed both of your pieces … it has alway been puzzling why an old soldier like Sherman felt empowerd to offer terms beyond what Grant had offered … he was clearly way out-of-bounds … and then he expects them to be approved by Stanton … definitely bad headwork by Uncle Billy!!!