Chancellorsville: R. E. Lee’s Greatest Pyrrhic Victory

This blog expands on the discussion Ryan Quint wrote in his 2022 ECW blog, “More than Just Jackson” and Chris Mackowski’s and Kris White’s Chancellorsville research.[1]

What’s a “Pyrrhic victory?” It’s a victory that results in such a heavy toll it negates any true sense of achievement, or a victory in which a commander loses more than he gains. The term dates back to King Pyrrhus, king of the most powerful Greek tribes. He reigned intermittently between 306 and 272 BC. After one battle, King Pyrrhus lamented: “One more such victory and we are undone.”

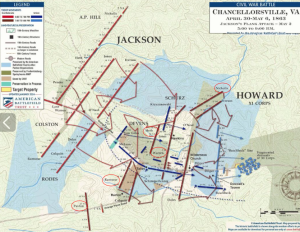

The tactical victory at Chancellorsville cost General R. E. Lee more than he could afford. He lost so many good regimental and brigade commanders his front-line command structure was strategically destabilized. This was significant! Remember, most of the battles were fought at the regimental and brigade level. Corps and division generals maneuvered their men into position. It was the front-line officers who led the brigades and regiments into the pall of battle, while the mid-level division and corps commanders oversaw the action usually (but not always) from the rear.[2]

Considering this, let’s look at the casualty list. Among the 60,000 Confederates committed to the fight, the enlisted (privates, corporals, sergeants) casualties numbered 1,546 killed, 8,591 wounded, and 1,636 missing. The officer cadre suffered 103 killed, 515 wounded, and 72 missing. The casualties amounted to 11,773 enlisted and 690 officers, or roughly 22% of his army. Many wounded died, while others suffered from unrecoverable injuries and never returned to the ranks. Somehow, Lee replenished his enlisted numbers at least for a time. The loss, however, among his front-line officer cadre was another story, especially among his Second Corps, aka Lt. Gen. Thomas Jackson’s wing.

At least 40 regimental commanders (colonels and lieutenant colonels and majors) fell killed or wounded. In some cases, captains found themselves in the role of colonel. Capt. N. A. Pool was the ranking officer of the 7th North Carolina.[3] That’s a big jump in responsibility. These 20-something-year-olds were thrown in the deep end, having to gain their experience in combat. This wasn’t an impossible task, but it wasn’t ideal. Losing a heavy toll on the line officers also meant there were fewer qualified personnel available to replace the brigade commanders.

The most well-known brigadier general casualty was an up-in-coming Virginian officer. Brigadier General Elisha F. “Bull” Paxton commanded the famed Stonewall Jackson brigade. On the morning of May 3, 1863, he was killed in action. Colonel John H. S. Funk took command of the brigade and made it through the battle.[4] At least 23 officers and 470 enlisted fell killed or wounded in the brigade. Douglas Freeman wasn’t being dramatic when he noted that the Stonewall Brigade “was never itself in full might after that battle.”[5] Incredibly, other brigades suffered even higher casualties.

Brigade Commander Colonel E. T. H. Warren’s brigade got hit the hardest (10th, 22nd, and 37th Virginia Infantry and 1st and 3rd North Carolina). He fell wounded but survived. The fighting was so brutal the brigade couldn’t keep a commander for more than a few minutes: Colonel T. V. Williams (wounded/survived), Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Walker (mortally wounded), Colonel John A. McDowell (wounded/survived), and Lieutenant Colonel S. D. Thruston (wounded/survived). Lieutenant Colonel H. A. Brown led the brigade at the end of the battle.[6] The brigade’s total casualties amounted to 590 killed or wounded.[7]

The South Carolinians had a rough go in Brigadier General Samuel McGowan’s brigade on May 3, 1863. McGowan took a minié ball below the knee and spent months recovering. Colonel O. E. Edwards assumed command, but he went down mortally wounded. Colonel James M. Perrin was third-in-command, but he was fatally wounded before he had a chance to take command. Colonel Abner Perrin briefly took over part of the brigade and then handed it over to the senior officer, Colonel D. H. Hamilton. Perrin and Hamilton survived Chancellorsville. The casualties amounted to 369 killed and wounded.[8]

Other brigades and their commanders in the Second Corps took a beating as well. Brigade Commander Colonel Thomas S. Garnett fell mortally wounded; he was succeeded by Colonel A. S. Vandeventer, who survived the battle. Garnett’s brigade counted 472 killed or wounded.[9] Brigadier General Robert F. Hoke was gravely wounded near Fredericksburg. Colonel Isaac Avery took command of the brigade and survived the battle. Hoke lost 230 killed or wounded.[10] Brigadier General Francis T. Nicholls was wounded and had his left leg amputated. Colonel Jesse M. Williams replaced him and survived. Nicholls’ casualties added up to 463 killed or wounded.[11]

Finally, three brigadier generals were slightly injured. Henry Heth and Dorsey Pender received minor wounds and were promoted to division commands in Lee’s re-structured army after Chancellorsville. S.D. Ramseur suffered a second wound at Chancellorsville. He recovered in time to lead his brigade at Gettysburg.[12] With Heth and Pender division commanders, this left two more brigade billets needing to be filled.

All told, 40 regiments and eight brigades needed skilled commanders. All eight brigades were in the Second Corps. To put that in perspective, on average, 20 regiments made up a division, two divisions-worth needed to find experienced regimental commanders. Four-to-five brigades comprised a division. One division and change had to find experienced personnel to lead the brigades. Lee couldn’t replace these line officers fast enough.[13] As such, Lee never fielded an army with such high caliber tactical leaders across the board. Sure good commanders stepped up here and there but not like those in May of 1863 at Chancellorsville. The Chancellorsville Campaign was at the very least Second Corps’ high water mark if not the entire Army of Northern Virginia’s.[14]

[1] Thank you to Chris Mackowski for taking the time to edit an initial draft. https://emergingcivilwar.com/2022/05/07/more-than-just-jackson-the-army-of-northern-virginias-casualties-in-the-officer-corps-at-chancellorsville. Chris Mackowski and Kris White, Chancellorsville: “The High Tide of the Confederacy” and Chapter Five

“The Cresting Tide: Robert E. Lee and the Road to Chancellorsville,” Kristopher D. White, https://emergingcivilwar.com/publication/turning-points-chapter-five.

For more on Chancellorsville https://history.army.mil/staffRides/_docs/staffRide_Chancellorsville.pdf.

[2] Yes, Thomas Jackson and A.P. Hill were both wounded while at the front, but they were assessing the progress of the attack. The generals weren’t leading their brigades and regiments. Topography generally didn’t allow for an entire division or corps to fit onto a field at one time (yes, there were exceptions, but that’s another blog).

[3] O.R. Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 1, 918-19.

[4] See https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/paxton/paxton.html. Funk did not command the Stonewall Brigade at Gettysburg. Colonel Walker did.

[5] Douglas Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants, II, 650.

[6] O.R. Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 1, 1031-33.

[7] Ibid., 809.

[8] O.R. Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 1, 901-13 and 807. Abner Perrin commanded the brigade at Gettysburg. McGowan returned to duty in 1864. See also, James Fitz Caldwell, The History of a Brigade of South Carolinians, Known First as “Gregg’s” and Subsequently as “McGowan’s Brigade”, 1866.

[9] O.R. Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 1, 809.

[10] O.R. Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 1, 808. Colonel Isaac Avery led the brigade at Gettysburg. Avery was killed during the final assault on July 3, 1863.

[11] O.R. Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 1, 809. Colonel J. M. Williams commanded Nicholls’ five Louisiana regiments at Gettysburg.

[12] His brigade served in Robert Rodes’ Division, Richard Ewell’s Corps.

[13] Finding qualified leaders was made more difficult because regiments and brigades wanted to be led by an officer from their own state, i.e. Virginia officers couldn’t lead North Carolina regiments or brigades and vice versa.

[14] My colleagues, Chris Mackowski and Kris White, believe Chancellorsville was the Confederacy’s high water mark. I think the Confederacy’s high water mark occurred at First Manassas, July 1861. This is another rabbit hole.

A superior analysis on the leadership loss in the ANV at Chancellorsville! Just a minor correction on note number 10. Avery died July 3 but was mortally wounded in the evening attack on Cemetery Hill on July 2.

An excellently researched article! More scholarship like this is needed.

I personally am of the old school mind that Gettysburg was the high-water mark of the Confederacy; that its power and potential to accede recognition as a sovereign nation was at its zenith there. But all the heuristic debate about this can only be a good thing.

thanks Joanna — rock solid, detailed scholarship in your piece.

R.E. Lee would have likely agreed with your pyrrhic victory argument … after Chancellorsville, Lee was reported to have said: “At Chancellorsville we gained another victory; our people were wild with delight – I, on the contrary, was more depressed than after Fredericksburg; our loss was severe, and again we had gained not an in inch of ground and the enemy could not be pursued.”

Thank you! Unfortunately, Lee was trying to win the war with only aggressive tactics – he didn’t have a cohesive grand strategy. He thought aggressive tactics would work because they worked during the Mexican War. The Mexican War was like Desert Storm – limited in political and military ends, ways, and means.

Very good post. Kris White made a similar argument an ABT video that between Seven Days and the end of Chancellorsville Lee lost over 90,000 casualties, which was more than his original army. The South was bled white.

Well done JoAnna!!!

Like many others, I have focused on the relationship between Lee and Jackson—and how Jackson’s death had been an unrecoverable loss for Lee.

Your research clearly changes, at least for me, that level of importance.

The actual costs were not that apparent until you laid them out so clearly; “40 regiments and 8 brigades needed skilled commanders. All eight brigades were in the Second Corps. . . .”

Those are losses, regardless of Jackson’s death, that just couldn’t be replaced or trained-up to the standard Lee needed to continue successful operations.

Great article. For the layman guy like me, is there an average number, say if 2,000 men are wounded in battle, is there a rough estimate how many wouldn’t return for 3 months and how many would never return? TIA

Thank you! That’s a tough question. Have to look for books on casualty rates. Some soldiers didn’t go back cause of battle and war fatigue, not just a physical aspect. I don’t blame them.

With the loss of so many leaders at all levels, and of all ranks, Lee’s decision to recast his army from two corps into three seemed pretty risky. It is my understanding that such a move was in the works well before the engagement at Chancellorsville, but it was indeed carried out after that. My question is this: did Lee ulitimately do the reorganization because of Stonewall’s demise, or in spite of it?

Thank you! Yes, Lee reorganized due to Jackson’s death. It was risky. And then taking a newly reorganized army on aggressive operations. The Pennsylvania Campaign, the marching to PA and from PA was fine. But look at the Battle of Gettysburg from a brigade and regimental level, and it’s clunky for the CSA – lack of communication is going to occur when you have a newly structured army.